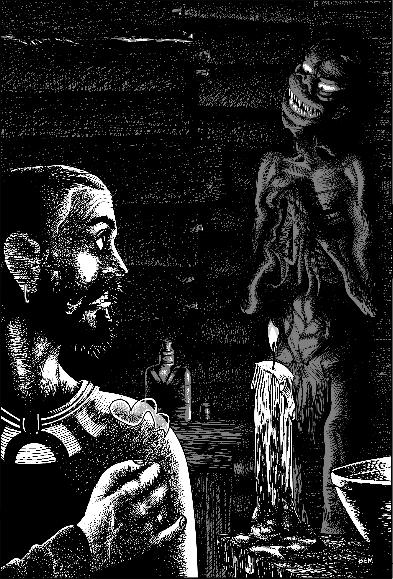

Fiction Excerpt: “Looking for Goats, Finding Monkeys”

By Iain Rowan

Illustrated by Bernie Mireault

from Black Gate 6, copyright © 2003 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

I blew out the candle, and the room went dark. I could hear water dripping from the edges of the bronze bowl that sat in the center of the table. I could hear the quick breaths of the woman, the studiedly calm breathing of her husband, and I could hear no sound from the children at all. I let a small pebble roll from the folds of my sleeve into my hand. The family waited. I sat patiently for another minute. Then I tossed the pebble into the water and the bowl erupted into a fizzing, crackling frenzy.

I blew out the candle, and the room went dark. I could hear water dripping from the edges of the bronze bowl that sat in the center of the table. I could hear the quick breaths of the woman, the studiedly calm breathing of her husband, and I could hear no sound from the children at all. I let a small pebble roll from the folds of my sleeve into my hand. The family waited. I sat patiently for another minute. Then I tossed the pebble into the water and the bowl erupted into a fizzing, crackling frenzy.

The mother screamed, the father let out a grunt, the children said nothing.

“Be calm,” I said. “They are upon us. Be calm and remain still. Remain where you are and all will be well.”

The pebble spluttered around in the bowl for a few moments and then the sound died away. I made some doggerel up on the spot and chanted it solemnly, letting the final notes reverberate in my throat. Then silence. I let it stretch on and on until the point when I judged that one of the family was about to give in and speak, and then I kicked the underside of the table. Hard.

I had to raise my voice to a roar to be heard above the panic; the children had obviously forsaken their vow of silence.

“Be calm, they are upon us now and we must be strong. I cast this dust into the air that it may blow away in the night and take these restless spirits with it like sand in a typhoon. As it is written in the ancient carvings of the hidden temples which must not be named, so I do dare speak it.” And so on, for a full minute of sacred oaths and hidden catacombs and vengeful elementals and other fantasies. Paint the grains gold, and a fool will sell you a horse for a small bag of rice.

I spoke the last few words, something to do with the fiery eyes of the mountain god Li-Shen. It was the one part of my performance that I had not invented. I had been browsing through manuscripts in a dusty shop owned by a dusty man when I came across a volume of Sacred And Ancient Rites of Exorcism, or some such nonsense. I did not buy it. I was there looking for some of the exquisite illustrated works of erotica that Dah-Lang produced before he went mad and took to living in a barrel, not dry superstitious nonsense but one phrase from it stuck in my mind, and I added it to my mumbo-jumbo. A touch of verisimilitude that amused me.

I tossed another pebble into the bowl. As it hit the water it let out a piercing shriek and burst into a brilliant green light which vanished as quickly as it had flared, dazzling the eyes and leaving incandescent clouds floating across the darkness. Unless you had shut your eyes in readiness, of course. I clapped my hands as loudly as I could, once, twice, three times. Then there was darkness and silence. I waited a few seconds more, and then struck a sulphur match along the edge of the table, lifting it as it flared so that it illuminated my solemn face.

I paused. Not too long though: once I had let the match burn my fingers, and remaining dignified had become a true test of my talents.

“It is done,” I said. I leant forward and lit the candle. “They are gone.” As I uttered the last word I pulled the match up to my lips, one side of my solemn face in shadow, the other lit by the flame.

“Gone,” I said again, paused, and blew the match out.

The family sighed as one. I leant back in my chair and smiled benevolently, stroking my beard.

“Don’t worry, children. It is all over.” Four eyes blinked at me. To be quite honest (an art in which I sometimes lack practice) I would rather the mother and father had left the children with an aunt, or dispatched them to the market to fetch some stringy mutton. An exorcism was no place for children, even if it was only smoke and chemical salts and much stentorian chanting in the deepest voice that years of practice could achieve. Foolish, superstitious mother and father though, convinced that their bad luck and curdled milk and broken tools were the work of a mischievous and restless ancestor, insisted that the children be present.

“They’re not too young to learn the lessons of the real world,” pronounced dull witted father. “They’ll sit where they’re told and not argue,” snapped shrewish mother. And so the children sat, clutching each other’s hands, terrified by the smoke and the chanting and their parents’ fear.

I smiled at the children with my most encouraging avuncular smile. The little girl burst into tears.

“Open the shutters, honored father,” I commanded. “Let the cleansing light of the sun shine in on this most purified of homes.”

As the man moved ponderously from window to window, pulling away the wooden boards, I gathered together my charms and accoutrements and magic sticks and pieces of holy rock. When enough of the boards had been removed to let the light in, I slowly lifted my hand and pointed to the brass bowl which sat in the middle of the table. The water in it had turned a deep blood red.

“There,” I said. “Therein lies the remains on this plane of the spirit which plagued your hearth. I have banished its incorporeal form to a plane many times separated from here by icy wastes and fiery seas. Its corporeal form I have bound to that water. I shall remove it from this place, and pour it into the dust of a crossroads with much solemn chanting according to the most ancient of sacred rites.”

“And our house will be free?” the father asked.

“Your house will be free.” I fastened the lid on to the brass bowl, and rose to my feet. The mother waved her hand imperiously at her husband and he stumbled across the room, bent down and fumbled with the floorboards under the stove, and returned with some bronze coins. I bowed my thanks, put the coins into my purse, carefully lifted the bowl and walked out without another word. The milk would still curdle, the tools would still break, but now they would blame his clumsiness, her housekeeping, and not vengeful sprites or malevolent ancestors. When you have a goat, and your flowers are eaten, you don’t look for a monkey to blame.

Only one full change of the moon later, one hazy summer afternoon when the heat baked cracks in the roads and every breath provided just a little bit less air than was needed, the monkey found me.

I had not worked for a few days. The exorcising of an imagined malicious uncle of a minor nobleman had bought me a few days rest. I spent most of the first day eating, most of the first night drinking, and most of the next day in the welcoming bed of one of Mother Shen’s girls. This delightful cycle repeated itself for a few days, but in the end the old serpents raised their cunning heads and I was powerless to resist. I forsook the warm, soft sheets and warmer, softer girl for a hard wooden chair in a smoky, dimly-lit room, where moon tiles clicked and clacked as they were laid down on the rough wooden table, and small fortunes were won and lost. Lost, in my case.

So I found myself back in search of work rather sooner than I might have wished. Business was slack in the city: the spirit world had taken a back seat to the physical world. For days a stream of dust-caked soldiers with haunted eyes had come stumbling back through the city gates, mumbling stories of the supposedly invincible Golden Army being slaughtered like cattle, of the sound like thunder that presaged another horde of the horse-borne barbarians pouring over a hill, of the one prisoner set free by the barbarians, released to bear the message back that one day the thunder would be heard at the gates of the Eternal Palace itself.

In times like these there was less call for my services. I made polite enquiries with the local watch in all parts of the city, hung my banner in the major markets, ate only soup with bread, and waited. Eventually my patience was rewarded. I had returned from a wasted visit to a particularly surly watch captain, who had told me that any evil revenants in his streets would be dealt with by cold steel and hot courage, and found one of the local street boys sitting on my porch.

“Be gone, louse of the most infested monkey,” I growled. “I have no work for you today. I have no work for you any day.”

He grinned insolently and toothlessly at me, and did not move from my porch. I may be a manipulator of the gullible, but even in my darkest hours I do not stoop so low as those charlatans who buy the teeth from children’s mouths to grind up and sell to impotent rich merchants as curative powders. I do stoop low enough, however, to kick children who should have more respect for their elders.

I had lead him by his ear to the road before he finally managed to inform me that he was not loitering outside my humble residence solely for the purpose of annoying me, but because he carried a message for me. I set him down, scolded him for not telling me straight away, and headed off his passionate protests of mortal injury by fumbling in my purse. He eyed the coin greedily, but I held my hand up in the air.

“The message first, child of a rat.”

“How do I know you’ll give me the money?”

“If I give you the money, born-to-hang, how do I know you’ll give me the message?”

He thought about this, and then nodded and produced a dirty piece of parchment from within an even dirtier shirt. He handed it over, and waited while I puzzled over the ill-educated scrawl. A farmer from outside the city walls, a house with strange smells and noises and a plague of bad luck undoubtedly the work of a cursed and tormented ancestor, humbly requested my esteemed services at my soonest convenience, pledged payment and eternal gratitude, forever my most humble… and so it went on in this vein, until the author ran out of flattery. I held the coin out to the boy, but as he reached to grab it I raised it just out of his reach again.

“A message back. The man who sent you will pay you for it. Just tell him, I come tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow, you come tomorrow.” The boy nodded again, dancing from foot to foot. I brought down my hand and the coin and the boy were both gone within an instant, racing away down the street.

One thought on “Fiction Excerpt: “Looking for Goats, Finding Monkeys””