“Authenticity” in Sword & Sorcery Fiction

Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?

These days, in intersection with my Conan gaming (I enjoy both Monolith’s board game and Modiphius’s roleplaying game), I have been reading a lot of two things: weird fiction from the turn of last century into, maybe, the 1940s; and sword & sorcery — anything that, on its cover, features a muscled male wielding medieval weaponry — predominantly from the ‘70s or ‘80s. (This latter does the double duty of encouraging me to work out.)

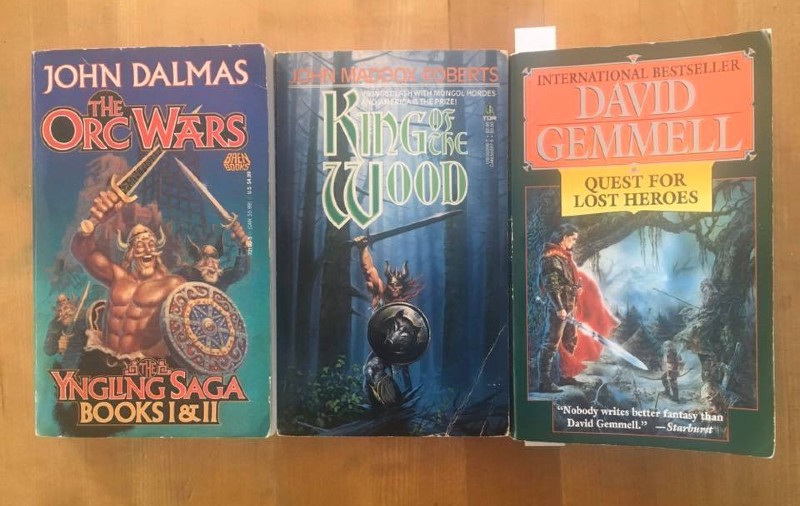

As is to be expected, these works offer various levels of quality. Early-last-century weird fiction is in a class of its own, and, though writers of that era freely borrowed tropes, themes and elements from each other (they very much appear to have been in conversation, literally or otherwise), the form of the weird tale is not as calcified as that of sword & sorcery appears to be by the ‘80s. Even within this latter’s straitjacket, however, I have encountered some standouts, including John Dalmas’s The Orc Wars (beginning with The Yngling, 1971), Gordon Dickson’s and Roland Green’s Jamie the Red (an unofficial Thieves’ World novel, 1984), and John Maddox Robert’s The King of the Wood (1983). Why I like these is for the reasons that one would like any work of fiction, of course, but with one addition: they present a sense of verisimilitude. I should add here, for anyone who might not be privy to how sword & sorcery is supposed to be subdivided from its parent genre of fantasy, that sword & sorcery is supposed to be more “realistic.” The world presented in such tales is premodern. Life is hard. The cultures do not have our present technology (nor magic — magic, in this subgenre, if not “low,” is rare and mysterious and terrifying and usually very, very “wrong”) with which to ease the drudgery of existence. In other words, the characters in such stories live in the way that folks in the Middle Ages lived, possibly in the way that many of our grandparents or great-grandparents lived, if they were homesteading somewhere.

This is why I no longer write sword & sorcery. I am a city boy. I am modern. I have no idea what “real life” is like. And yet I somehow have enough of one to know — intuitively or otherwise — when a writer knows even less than I do. To catalog the many errors of some of our most famous current fantasy writers is outside of the scope of these observations, but I’ll point to the occasion that spurred me finally to write on this topic here.