Robert E. Howard: The Day That I Was Born

Robert E. Howard, author and poet, was born on January 22, 1906. In an undated letter to his friend Clyde Smith (“Salaam/Again glancing…), Howard wrote of this day in the poem, “I Praise My Nativity.”

“Oh, evil the day that I was born, like a tale that a witch has told;

I came to birth on a bitter morn, when the sky was dim and cold.

The god that girds the loins of Fate and sends the nighttime rain,

He diced my game on an iron plate with dice carved out of pain.

“This for the shadow of hope,” laughed he, as the numbers glinted up,

“This for a spell and this for Hell, and this for the bitter cup.”

A Shadow came out of the gloom of night and covered me with his cowl

That carried the curse of The Truer Sight and the blindness of the owl.

Oh, evil the day that I was born, triply I curse that day,

And I would to God I had died that morn and passed like the ocean spray.”

While he may have wished to God that he had died that morn, as one of his legions of fans, I’m grateful that he didn’t. And I have about twelve hundred reasons for my gratitude: the over four hundred short stories and more than seven hundred poems that he wrote.

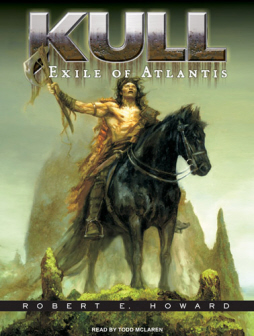

Unlike many of the Black Gate readers, I’m relatively new to the writings of Robert E. Howard. I became interested in him when I saw the movie The Whole Wide World in 2006. I started with the Del Reys: The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane and Kull Exile of Atlantis. I also read my way enthusiastically through all the Conan stories and then everything else of Howard’s I could get my hands on. I haunted the REH eBay offerings looking for the books and stories I didn’t have.

My efforts were rewarded. I was *there* when Dark Agnes, Valeria and Howard’s strong women flashed their swords and fought beside men as equals. I laughed out loud at Meet Cap’n Kidd and the other Breckenridge Elkins tales, relished Lord of Samarcand and chewed my nails during Pigeons in Hell.

Not to beat the subject, like Fingon, to death, but neither writer is trod into the mire by a comparison to the other. The shortest distance between these two towers is the straight line they draw and defend against the dulling of our sense of wonder, the deadening of our sense of loss, and the slow death of imagination denied.

Not to beat the subject, like Fingon, to death, but neither writer is trod into the mire by a comparison to the other. The shortest distance between these two towers is the straight line they draw and defend against the dulling of our sense of wonder, the deadening of our sense of loss, and the slow death of imagination denied. Another year’s drawing to a close, and with it the first full decade of the twenty-first century. It’s a time for looking back, for thinking over what’s happened and what’s going on, in fantasy fiction and elsewhere. I don’t pretend to be in a position to make any worthwhile assessment of fantasy as a whole; but I do want to write about a change that seems to be in process right now. I think it’s a positive change, and potentially a radical one. And I can remember the moment I realised it was happening.

Another year’s drawing to a close, and with it the first full decade of the twenty-first century. It’s a time for looking back, for thinking over what’s happened and what’s going on, in fantasy fiction and elsewhere. I don’t pretend to be in a position to make any worthwhile assessment of fantasy as a whole; but I do want to write about a change that seems to be in process right now. I think it’s a positive change, and potentially a radical one. And I can remember the moment I realised it was happening. Conan the Renegade

Conan the Renegade Conan and the Amazon

Conan and the Amazon

Let us die in the doing of deeds for his sake;

Let us die in the doing of deeds for his sake; 3. The Saxon Stories, Bernard Cornwell. Uhtred of Bebbanburg is a Saxon youth captured and raised among the Danes, who then proceeds to spend the next several books in this yet-unfinished series fighting alternately for both sides in war-torn 9th century England. The Saxon Stories features Cornwell, a brilliant historical fiction writer, at his near-best (though I still prefer his Warlord Trilogy) with Viking raids, shield walls, axes, dark ages combat, hall-burnings, and general mayhem galore. Great stuff.

3. The Saxon Stories, Bernard Cornwell. Uhtred of Bebbanburg is a Saxon youth captured and raised among the Danes, who then proceeds to spend the next several books in this yet-unfinished series fighting alternately for both sides in war-torn 9th century England. The Saxon Stories features Cornwell, a brilliant historical fiction writer, at his near-best (though I still prefer his Warlord Trilogy) with Viking raids, shield walls, axes, dark ages combat, hall-burnings, and general mayhem galore. Great stuff. Am I a bad gamer if I really, really want to play this game?

Am I a bad gamer if I really, really want to play this game? “Beyond the Sunrise” is the unofficial title afforded an unfinished Kull story that did not see print until over forty years after the author’s death. Its significance is due largely to the fact that it was the first of four widely differing attempts to continue the Kull series following the publication of both “The Shadow Kingdom” and “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune” in Weird Tales in 1929.

“Beyond the Sunrise” is the unofficial title afforded an unfinished Kull story that did not see print until over forty years after the author’s death. Its significance is due largely to the fact that it was the first of four widely differing attempts to continue the Kull series following the publication of both “The Shadow Kingdom” and “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune” in Weird Tales in 1929.