Mars Missions, Vengeful Djinn, and Haunted Dolls: The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1952, a Retro-Review

|

|

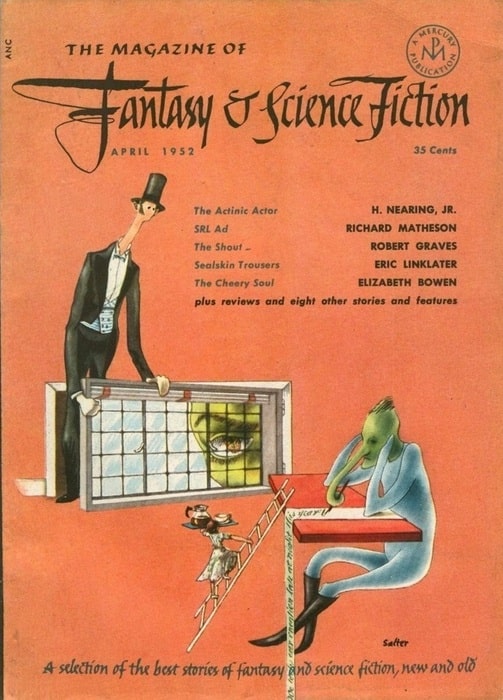

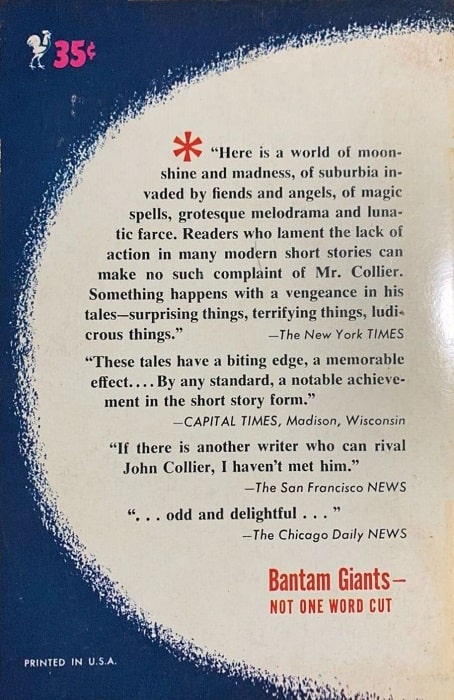

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1952 (Mercury Press). Cover by George Salter

In its early years, one of the most notable characteristics of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction was its regular use of reprints — fantastical stories from outside the genre, often by very well-known writers, given exposure to SF and Fantasy readers. Another notable characteristic was covers by its art director, George Salter.

Both aspects are features of this issue — indeed, this seems almost a comically pure exemplar of the Boucher/McComas era. I’ll highlight the non-genre history of some of the writers in the issue. (As for Salter, I enjoy his delightfully weird art quite a bit.)

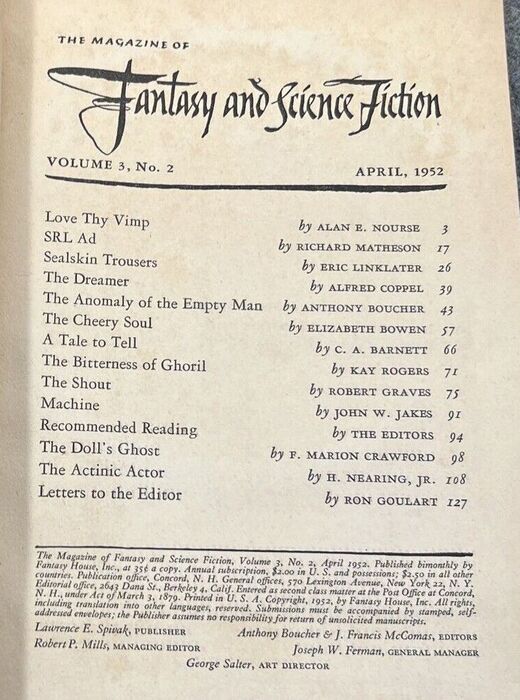

Here are the stories. There is also one feature, “Recommended Reading,” by the Editors.

[Click the images for magazine-sized versions.]

Table of Contents for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1952

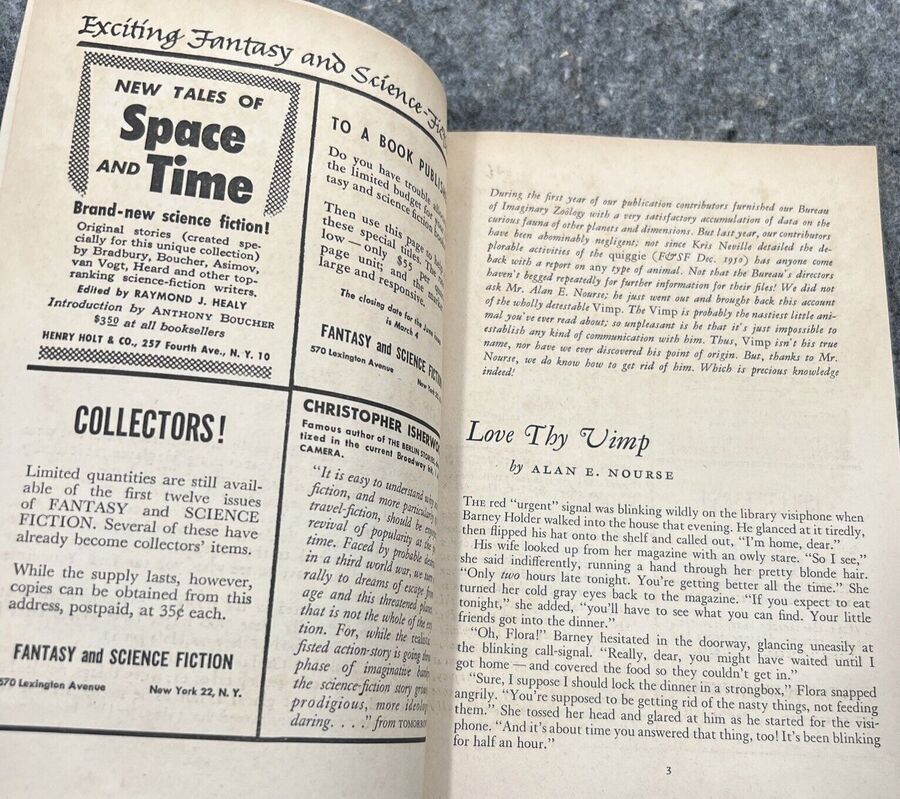

“Love Thy Vimp,” by Alan E. Nourse (6,000 words)

“SRL Ad,” by Richard Matheson (3,000 words)

“Sealskin Trousers,” by Eric Linklater (5,500 words)

“The Dreamer,” by Alfred Coppel (1,300 words)

“The Anomaly of the Empty Man,” by Anthony Boucher (5,900 words)

“The Cheery Soul,” by Elizabeth Bowen (3,600 words)

“A Tale to Tell,” by C. A. Barnett (2,000 words)

“The Bitterness of Ghoril,” by Kay Rogers (1,600 words)

“The Shout,” by Robert Graves (7,000 words)

“Machine,” by John W. Jakes (1,200 words)

“The Doll’s Ghost,” by F. Marion Crawford (4,200 words)

“The Actinic Actor,” by H. Nearing, Jr. (8,300 words)

“Letters to the Editor,” by Ron Goulart (400 words)

I’ll just cover the stories in order.

“Love Thy Vimp” by Alan E. Nourse

“Love Thy Vimp” is one of Nourse’s first stories, and I found it disappointing. It concerns very unpleasant aliens — the vimps — who have invaded Earth through some accidentally opened portal. The main character is a researcher trying to figure out how to deal with the vimps, while he is variously browbeaten by his jealous wife and hard-driving boss. The title telegraphs the solution, and the story is never terribly interesting, though the ultimate moral — that treating humans better is a side effect of learning how to rid oneselves of the vimps — is well enough done.

Richard Matheson’s “SRL Ad” is a bit more amusing, an epistolary story about a female from Venus placing an ad in the Saturday Review of Literature, looking for a nice Earth guy… and the unfortunate results when an astronomy student answers the ad. Minor stuff, but enjoyable enough.

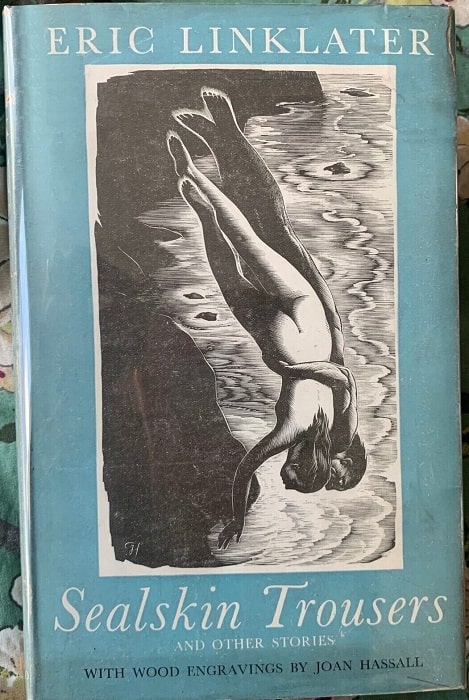

Sealskin Trousers and Other Stories,

by Eric Linklater (Hart-Davis, 1947). Cover artist unknown

“Sealskin Trousers” is a selkie story, written by Eric Linklater and reprinted from his 1947 collection of the same title. The story’s introduction treats Linklater as a household name, which was likely true in 1952 but is, alas, not at all true today. Linklater (1899-1974) was Welsh-born, but Scottish-raised, his father a Scotsman and his mother of part Swedish ancestry. After an abortive time training as a doctor, and some time spent in India and elsewhere, Linklater turned to writing, and also teaching and administrative positions at the University of Aberdeen.

He served with considerable distinction in both the First and Second World Wars. His wife was an actress, and so was one of his daughters, Kristin, who moved to the US. Kristin’s son Hamish Linklater is a somewhat prominent actor now, having appeared most recently in the horror series Midnight Mass, and previously in such movies as The Big Short, and TV series like The New Adventures of Old Christine. Eric Linklater himself was a successful novelist and memoirist, best known possibly for the children’s book The Wind on the Moon.

Hamish Linklater in Midnight Mass (Netflix)

The story concerns a young woman on vacation (presumably to a Scottish island, perhaps Linklater’s beloved Orkney) with her fiancé. One day, coming alone to a secluded spot she and her fiancé had discovered, she finds a man there — naked except for his curious sealskin trousers. To her surprise, she recognizes him — a man she had known slightly at university. And they talk for a bit, the man pressing her somewhat on her biological knowledge.

The reader will guess right away that he’s a selkie, and after some demonstrations of his prowess in the sea, he sets out to convince her that she too has the biological ability to become a selkie, and live with him in the sea… The story is framed by her fiancé’s admission that he’s had a terrible shock and is only now slightly recovered — the shock, of course, is the loss of his intended wife. The biology is nonsense (though the editors take care to present the story as SF and not fantasy) but the story is pretty effective.

|

|

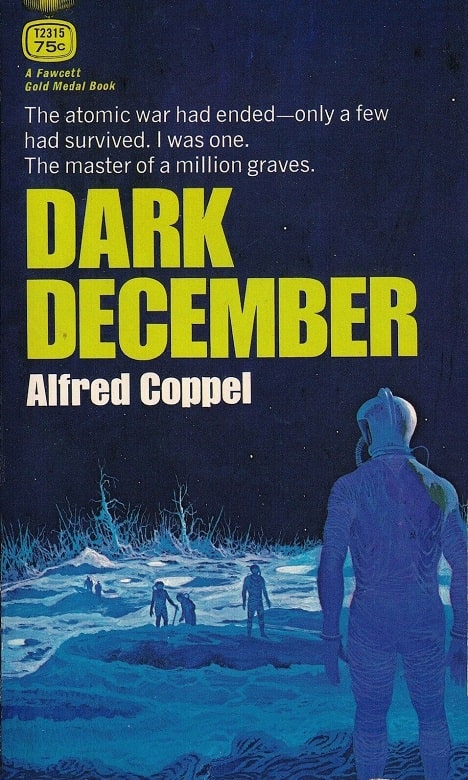

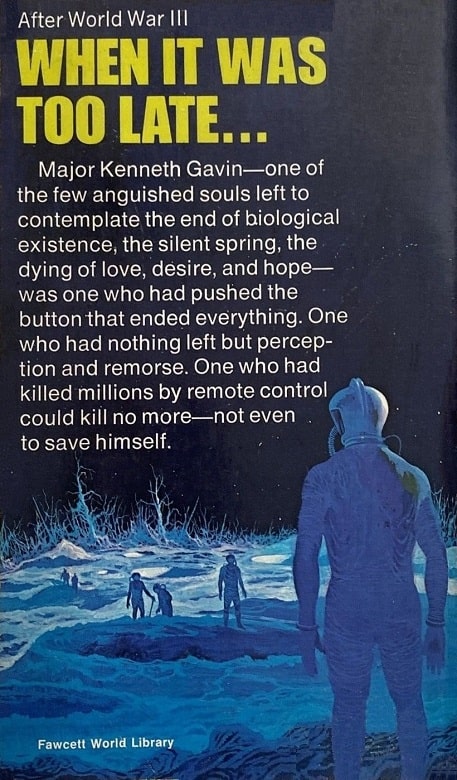

Dark December (Fawcett Gold Medal, October 1970). Cover artist unknown

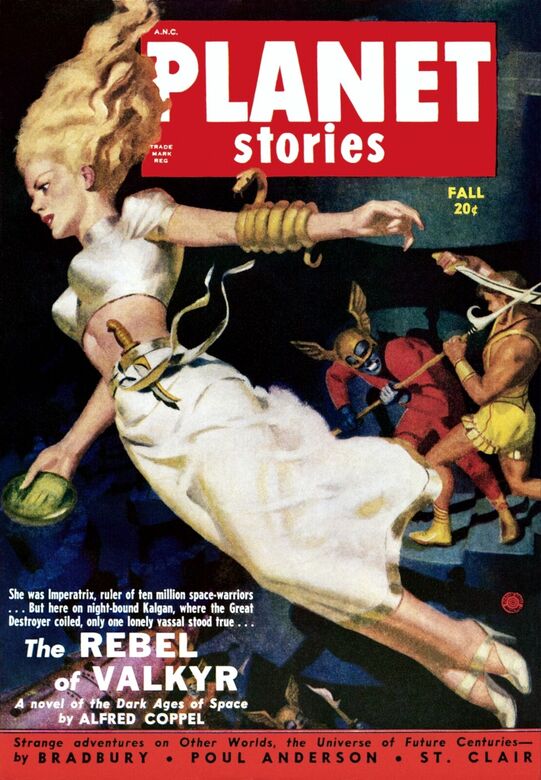

Alfred Coppel does not count as a writer from “outside the genre” — he wrote extensively for the SF magazines at the beginning of his career, and though he later established his reputation more widely, and had bestsellers, even much of that work, such as the post-apocalyptic novel Dark December and the near-future thriller Thirty-Four East, was at least borderline SF, and much was unapologetically SF. (Such as his YA Rhada tetralogy, written as by “Robert Cham Gilman,” that was based on a gleeful space opera novella from Planet Stories, “The Rebel of Valkyr.”)

“The Dreamer” is original to this issue of F&SF, and it is a worthwhile and somewhat bittersweet look at the SF enthusiast’s ambition to travel to other planets, as a man applies for a place on a Mars mission, and — well, read the story. It’s short, and effective.

Planet Stories, Fall 1950. Cover artist unknown.

“The Anomaly of the Empty Man” is by one of the magazine’s co-editors, Anthony Boucher, who of course was also a prominent writer and critic of crime fiction, as by “H. H. Holmes.” (“Anthony Boucher” is also a pseudonym — his real name was William Anthony Parker White.) His co-editor, J. Francis MacComas, assures the readers that this story was bought on his own authority alone, without influence from Boucher.

The story is mildly amusing but not Boucher at his best — the narrator is investigating the mysterious disappearance of a man from his home — leaving his clothes behind as if he was fully dressed and his body disintegrated. The missing man was an opera aficionado (as was Boucher) and the narrator goes to a certain Dr. Verner for help — Verner is writing a vast book called The Anatomy of Nonscience (sort of a combination of Richard Burton (of The Anatomy of Melancholy) and Charles Fort), and he is also an expert on music. The eccentric Dr. Verner suggests a very strange solution — even as the police have come up with a plausible naturalistic answer to the mystery. The story ends on a purposefully ambiguous note. (The blurb suggests that further Dr. Verner stories might be forthcoming, but none resulted. I do think the character had potential.)

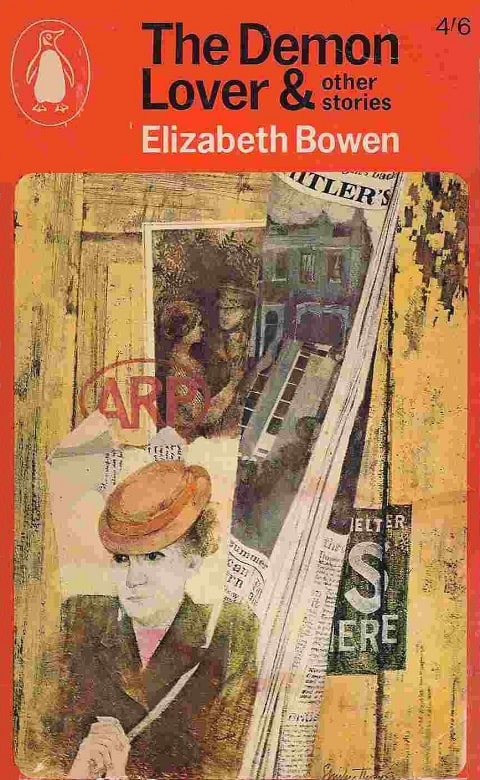

“The Cheery Soul” is by another great British (or, in her case, Anglo-Irish) woman writer of the mid-century, Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973). Bowen is perhaps best known for her 1938 novel The Death of the Heart. Though her novels were non-fantastic, her short fiction (and she was a great writer of short stories) often touched on fantastika, as hinted at by the title of her 1945 book, The Demon Lover and Other Stories, in which this story (first published in 1942) was collected. (I can recommend another story from that book, “Mysterious Kôr,” which abuts the fantastic without quite crossing the border.)

The Demon Lover and Other Stories by Elizabeth Bowen

(Penguin Books, 1966). Cover by Shirley Thompson

In “The Cheery Soul,” the narrator, billeted while doing war production work in a northern town, has accepted a Christmastime invitation to visit the reclusive but wealthy Rangerton-Kennys — but finds the place almost deserted but for a cranky Aunt who regrets having had to leave Italy due to the war; and for evidence of the old cook — who somehow cannot be found though she has left some odd messages. The blurb calls it a comic story, but it’s not quite that, though there are comic elements, as the resolution darkly hints at war-related crimes.

C. A. Barnett is credited with only one story in the ISFDB, his first (so says the blurb), “A Tale to Tell.” It’s a short dark piece set in a future in which “war, envy, and spite” have been abolished. A creature called IT is haunting a young girl, apparently trying to tempt her to sin by telling her a gruesome story of a witch. But IT is wholly frustrated — it seems to be having no success, and so gives up. And then there’s the twist … It’s minor work but not bad — I don’t know if the author did anything else in other fields or under other names, but in a way it’s the sort of story that might well have been the result of one idea that the writer worked out, but had no interest in further writing.

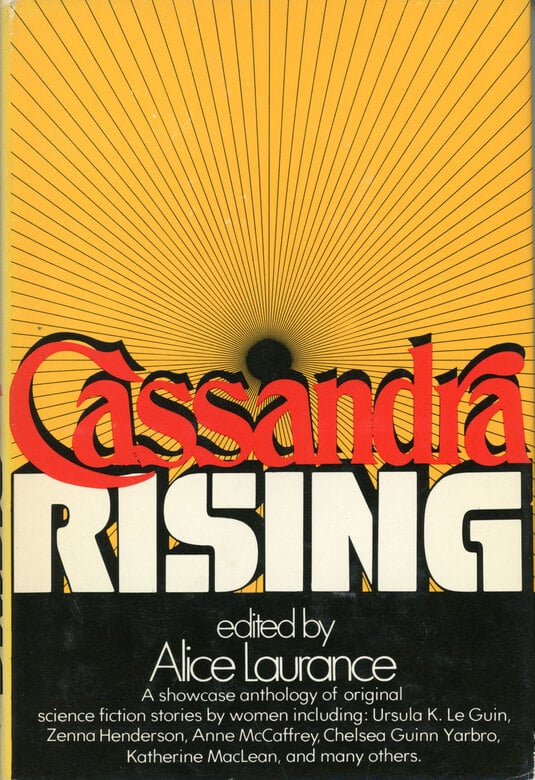

Cassandra Rising (Doubleday, August 1978). Cover by One Plus One Studio

Kay Rogers is another writer who doesn’t appear to have published much — five stories in F&SF between 1951 and 1954, then one more in 1978 in Alice Laurence’s original anthology of stories by women, Cassandra Rising. (Again, it’s possible she wrote in other fields.) “The Bitterness of Ghoril” concerns a djinn who is summoned by a present day American woman. The djinn is certain she will forget her bargain and he will be allowed to take revenge, but she finds a way to trick him. It’s a clever little piece.

The third major British writer to appear in this issue is Robert Graves (1895-1985), with “The Shout,” first published in 1929. Graves of course is very well known for a great variety of things — among them his memoir Good-Bye to All That; his study of poetry, The White Goddess; and his historical fiction, especially I, Claudius. His science fiction novel Seven Days in New Crete, aka Watch the North Wind Rise (1949), is also well regarded. “The Shout” is curiously framed by the narrator visiting an asylum to help score a cricket match between two teams of inmates. His fellow scorer is also an inmate, and he tells the narrator a story, about a happily married couple named Richard and Rachel. One day they meet a man near their (somewhat isolated) place, and they invite him for dinner. He tells them something of his travels, including to Australia, where he learned what he calls “The Shout,” which can kill or turn mad anyone who hears it. Richard is bothered by the man’s apparent interest in Rachel, but also feels compelled to insist on a demonstration of the “Shout,” in which he doesn’t quite believe. Sinister details mounts as they go off to a deserted place and… well, I won’t say. But it’s an intriguing story, with an odd slightly twisty ending (that many will to some degree guess.) Not an enduring classic, but a good story.

John Jakes made his bones writing pulp fiction of all sorts in the 1950s (his first story was published in 1950 when he was only 18), but a lot of his best-known early work was SF and Fantasy (notably the Brak the Barbarian stories and the novel On Wheels) until he got his big break when he was hired to write the Kent Family Chronicles, a paperback series of historical novels about the American Revolution, timed for release in the Bicentennial year, 1976. These were a big hit (I never read them but my wife did and enjoyed them quite a lot) and a further series followed, North and South, set during the Civil War. Both series became major bestsellers and spawned TV miniseries adaptations. Jakes continued to write mostly historical fiction, though he seems to have retired in about 2005. He is still alive at age 90. (I very briefly corresponded with him about his editorial relationship with Cele Goldsmith when he was selling her the Brak stories for Fantastic.) “Machine” is a brief and reasonably effective if predictable story about a man who becomes convinced his wife’s new toaster is after him.

|

|

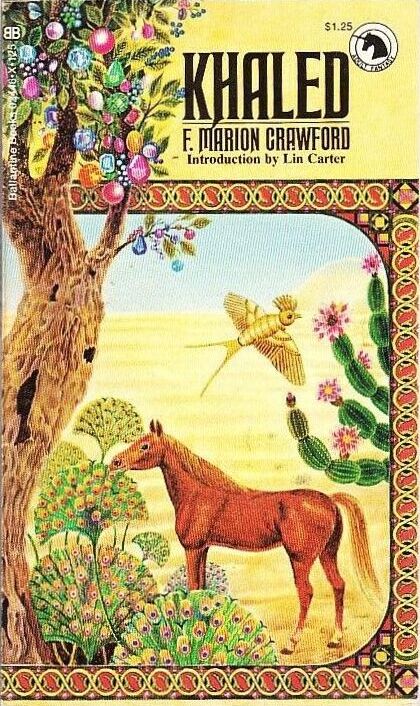

Khaled (Ballantine Adult Fantasy, December 1971). Cover by Gervasio Gallardo

F. Marion Crawford (1854-1909) was NOT a British writer — instead, he was an American (though born in Italy) who was a very popular writer around the turn of the 20th Century. Many of his most popular novels were historical novels set in Italy — I have read one, Marietta, about the founding of an influential (to this day!) family of glassmakers in Venice in the 15th century, and I found it quite enjoyable. He had one novel reprinted in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series — Khaled, about a genie who becomes a human. (I have a copy but haven’t yet read it.) He was also well-known for his ghost stories, of which “The Upper Berth” is the most famous by far. The story this issue, “The Doll’s Ghost,” first appeared in 1896. It’s about a porcelain doll who is broken when her owner falls down the stairs. The doll is taken to a master doll repairmen who is not quite able to repair her. And so the doll becomes a ghost — and when the repairman’s daughter is threatened the ghost comes to the rescue. It’s a nice enough little piece.

H. Nearing, Jr. (1915-2004), had the sort of name that made me think he was an English writer, and his story, one of a humorous series about a math professor, Cleanth Penn Ransom, whose extensive knowledge sometimes gets him into trouble, is the sort of thing one wouldn’t be surprised to be a reprint from earlier years. But Homer Nearing was an American, a professor himself (of English), and an expert on historical English poetry. He taught at Widener University near Philadelphia (then called Pennsylvania Military Academy.) And, in a coincidence (to me) his wife was Alice Eleanor Jones, who also had a Ph. D., and who wrote a few stories for the SF magazines in the 1950s, including a significant one “Created He Them,” from the June 1955 F&SF, which showed up in the mail just today! (Jones was also a prolific writer of mainstream stories for markets like Redbook.)

Nearing’s C. P. Ransom stories mostly appeared in F&SF (a few were original to the one collection of them). In “The Actinic Actor” Professor Ransom is determined to play the Ghost in Hamlet, even though he has no acting skill. His hated rival is a drama critic, and if he can’t learn his lines he’ll be mocked horribly — but his ace in the hole is a scheme to consume enough riboflavin to make his eyes flash and give the Ghost an eerie appearance that will make the flubbed lines a minor issue. Naturally, things go sideways. It’s amusing enough stuff, though nothing to write home about.

|

|

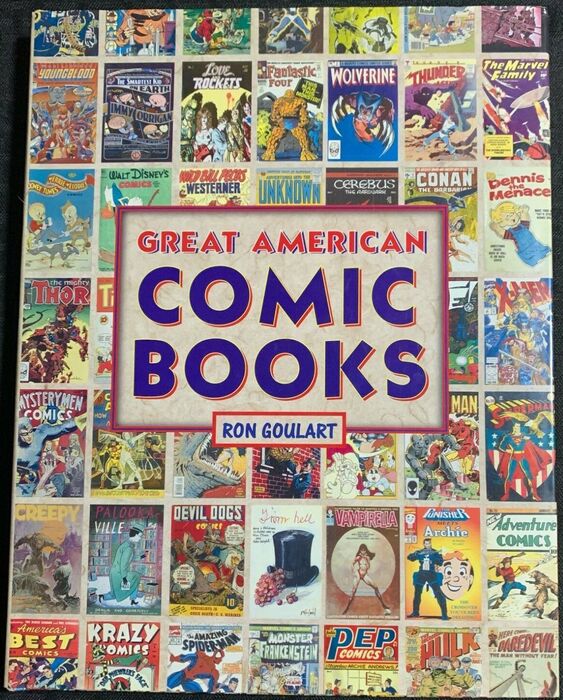

Great American Comic Books by Ron Goulart (Publications International, January 2001)

The last story is Ron Goulart’s first professional publication. Goulart was born in 1933 and died earlier this year, a day after his 89th birthday. Besides his SF he was a significant historian of pulp magazines and comics, including Great American Comic Books (2001). He also ghost-wrote William Shatner’s Tek War series. Within the field he was best known for his humorous stories, and “Letters to the Editor,” which first appeared in his college’s humor magazine, the University of California Pelican, in 1951, fits that mold.

It’s a one-page story cleverly parodying letters both praising and complaining about the stories in a pulp SF magazine. It’s interesting to think of the different SF careers of the two writers who had first sales in this issue: C. A. Barnett never published another story, and Ron Goulart’s career lasted over 60 years (and he published in F&SF throughout — his most recent story appeared in 2015.)

|

|

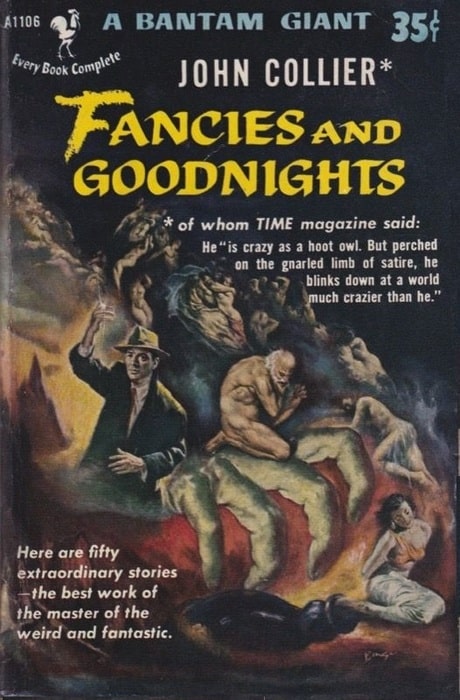

Fancies and Goodnights by John Collier (Bantam Books, April 1953). Cover by Charles Binger

The one feature is “Recommended Reading,” in which the editors survey the SF books published in 1951. They were apparently rather disappointed with the class of 1950, but confess themselves much happier with 1951, partly because there were more completely new novels as opposed to reprints, and partly because there were many good anthologies. Their highest praise goes to John Collier’s Fancies and Goodnights, of which they say: “We’ll go out on a limb: The largest number of truly great stories of the imagination ever contained in a volume by a single author.” By and large, I’d say, that assessment still holds up.

And one final note – I have often remarked that there seemed to be law in force in the 1950s, that every single issue of an SF magazine had to have a story about atomic war – either the threat of it, or the actual war, or a post-war story. And honestly I cannot remember a single issue that I’ve read – and I’ve read a lot – that didn’t have at least one such story. Until this one!

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a Retro-Review of the September 1953 issues of Universe. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Another children’s book by Linklater – The Pirates in the Deep Green Sea – has a similar conceit, with the qualification that people are able to live underwater thanks to a magic cream/oil. The title pretty much sums up the storyline, but It’s definitely worth checking out.

Aonghus,

You really are a font of knowledge of great old books. You should be on our staff!

I’ve never heard of The Pirates in the Deep Green Sea — but now that I have, it sounds like something I very much would have enjoyed as a young reader.

That’s the same copy I had! (It may even be lying around somewhere)

The Shout was made into a film starring John Hurt.

Steve,

Right you are! I was unaware of it, but THE SHOUT was released in 1978. It was directed by Jerzy Skolimowski, and also starred Susannah York and Alan Bates. Here’s the trailer.

I am unaware of any Indigenous Australians who could “shout” someone to death – I think this is a power invented by Graves for his story. The movie is an effective thriller and it’s interesting to see Hurt and York fairly early in their careers. Skolimowski also uses the landscape well to create an eerie feeling, the dunes taking on a decidedly sinister appearance.

It’s one of my favorite films but I’ve never got around to the story by Graves.