Retro-Review: Universe, September 1953

|

|

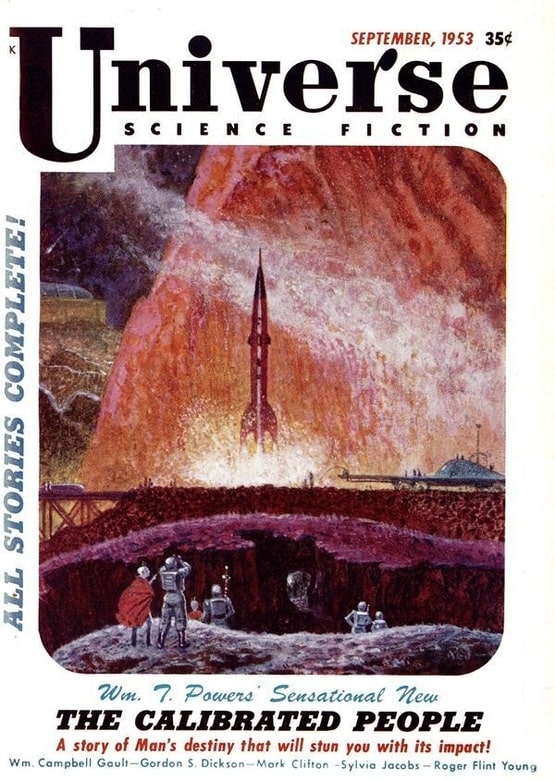

Universe, September 1953. Cover by Robert Gibson Jones

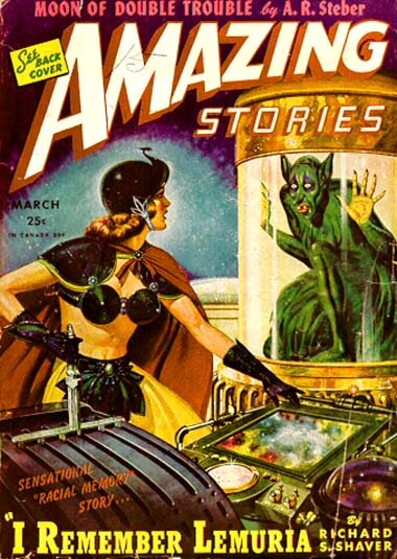

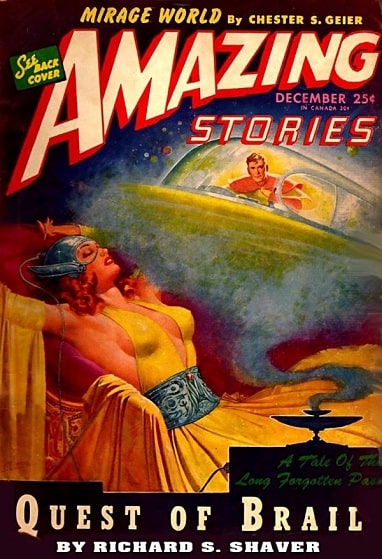

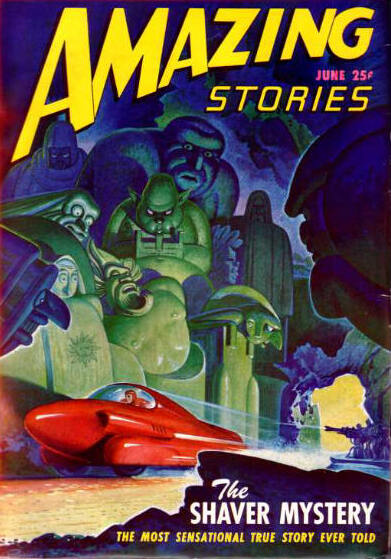

Universe was one of the many new science fiction magazines that appeared in the early 1950s. It was founded by Ray Palmer, the notorious editor of Amazing Stories during the 1940s, reviled for his promotion of the “Shaver Mystery” (about a race of people living underground.) He left Amazing when the publisher, Ziff-Davis, moved to New York. Palmer stayed in Chicago and started a magazine called Other Worlds Science Stories (published by Clark Publications.) Financial troubles led to the demise (temporarily, it turned out) of Other Worlds, and a new company, Bell Publications, was founded, and published two magazines: Science Stories, and Universe. The company was soon renamed Palmer Publications. Science Stories lasted four issues, and Universe ten, after which Palmer returned to the name Other Worlds Science Stories.

The editor at the beginning was “George Bell,” which meant Ray Palmer and Bea Mahaffey. After two issues of Universe, the editors were credited under their real names. Mahaffey was Palmer’s co-editor at Other Worlds, Science Stories, Universe, and another publication, Mystic Magazine, from late 1952 into 1955, at which time Palmer’s continuing financial issues caused him to lay her off. She is often credited with being the primary fiction editor of those magazines, and there is little disputing that the quality of the fiction was higher during her tenure than in Amazing before that, or in Palmer’s magazines after she was let go.

[Click on the images for Amazing versions.]

|

|

|

The Shaver Mystery in Amazing Stories: March 1945, December 1945, and June 1947. Covers by Robert Gibson Jones

Palmer, indeed, eventually concentrated on his interest in paranormal stuff such as flying saucers, divination, etc., especially in his long-running magazine Fate. All that said, Robert Silverberg reports submitting to Palmer’s magazines at the very start of his career, so he never actually sold to one of them, as by the time he hit his stride Palmer had more or less abandoned SF for the paranormal. Silverberg recalls receiving rejection letters in that period from both Palmer and Mahaffey, suggesting that Palmer did indeed have an active hand on the editing side.

One of the things Universe was known for was fairly adventurous content — stories that other SF magazines wouldn’t touch. The best known example of this is Theodore Sturgeon’s “The World Well Lost,” which appeared in the first issue, and which treated homosexuality sympathetically. But the issue I am covering here is the second, September 1953. And the stories here definitely show signs of an adventurous editor, even though they don’t all work.

The six stories are:

“The Calibrated People,” by W. T. Powers (12,000 words)

“Janushek,” by “Roger Flint Young” (Peter Grainger) (4,000 words)

“The Breaking of Jerry McCloud,” by Gordon R. Dickson (6,000 words)

“Election Campaign,” by William Campbell Gault (7,500 words)

“Up the Mountain or Down,” by Sylvia Jacobs (7,200 words)

“Reward for Valor,” by Mark Clifton (6,200 words)

William T. Powers was a quite significant scholar: trained in medicine and physics, he developed the Perceptual Control Theory, involving behavioral control of perception, which as far as I can tell is still well-regarded. He published seven SF stories, beginning with “Meteor” for Astounding in 1950. Four more followed in the 1950s, in Universe and Astounding, and his last two stories were in Galaxy in 1970 and 1971. He also published two science articles in Analog in the late ’60s. As with many (too many) SF writers, he was involved with Dianetics in the early 1950s, but soon dropped out of that movement.

“The Calibrated People” certainly shows an interest in psychology. Jon has just become an adult — a Class B citizen. He’s ten years old, and free of his parents, ready to choose his own schooling. He wants to be a spacer, and he want to go through Calibration. It doesn’t ever become quite clear what Calibration is, but it seems to involve getting full, exact, control of your brain — of its perceptions of the external world, and of its own workings. The story gives us a look at Jon’s experience at school, which reveals him to be a good student but unable to open up to the other students. And we learn what’s eating him — an apparently abusive relationship with his parents, that he refuses to allow himself to process, or anyone else to know. His teachers are convinced he will fail Calibration, particularly since he seems to be a Sensitive — basically, low-level ESP. All this is, if not precisely plausible, pretty interesting. Alas, the story wraps things up far too quickly, with a contrived “final examination” situation, and a hard to believe sudden revelation for Jon. An ambitious story, yes, but not quite finished.

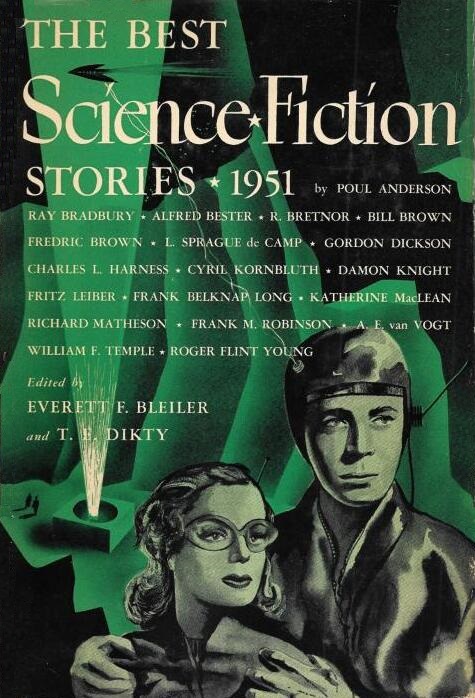

“Janushek” is one of five stories published under the name “Roger Flint Young.” The ISFDB credits these to Peter Grainger, who also published as “Peter Cartur” and “Max Dancey.” (Ignore that nutty suggestion on the ISFDB’s Grainger page that “Peter Cartur” might instead have been a pseudonym of Forrest J. Ackerman, based simply on the fact that Ackerman, as Grainger’s agent, gave permission to reprint one of his stories.) “Roger Flint Young” published one somewhat notable story, “Not to be Opened –” in the January 1950 Astounding, reprinted in the Everett Bleiler/T. E. Dikty anthology The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1951.

The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1951 (Frederick Fell, August 1951). Cover artist unknown

“Janushek” concerns a young recruit to the Guardians, a group who man a series of space stations carrying nuclear weapons, designed, apparently, to serve as a deterrent to any nuclear attacks by nations on Earth. He comes to his first post realizing that the program is underfunded and they are thus understaffed — and when a crisis arises, he is left the only person in position to make a truly wrenching decision. The story seems a bit artificial, a bit of a setup. Still, it is trying to make a point.

Gordon R. Dickson, easily the best-known writer in this issue, was early in his career at this point. “The Breaking of Jerry McCloud” tells of the title man, who wants to establish himself financially to allow he and his fiancée to marry. He is a proud man, so he spurns her parents offer of help, and sets off to a newly opened planet to make his fortune. But his first efforts fail, and he ends up being forced to take a desperate chance on stalking the dangerous bearlike Skem, an indigenous species that is prized for its musk-bag — all this as his girl has given him an ultimatum. The bulk of the story is something Dickson does very well — the depiction of his extended tracking of the Skem. But as he does so, he is forced to realize that the Skem are fairly intelligent — and very devoted to their mates… I thought it worked pretty well, really, even though the entire setup is clearly somewhat artificial.

As I have mentioned before, it was apparently a Federal law that a science fiction magazine published in the 1950s had to have at last one story about nuclear war per issue. “Janushek” is one, I suppose, and William Campbell Gault’s “Election Campaign” is another. Gault was a classic pulp/paperback writer of that era, writing under numerous names in almost any genre. He was best known, I think, for his YA sports novels — I recall encountering a couple at age 10 or 12 myself. He was also a prolific and popular writer of crime fiction. He published about a dozen Sf stories in the 1950s, in Galaxy, F&SF, and several of the less prominent magazines. The couple I’ve read have been thoroughly professional.

“Election Campaign” is set shortly after the twin disasters of a nuclear war and a plague have wiped out nearly everyone. Johnny Larson is a gangster, and he survived by pure accident. He’s getting by in a small shack he made, and the first other person he sees is a woman, recovering from the plague. They cooperate for a bit — he catching the plague and recovering as well — and then another group shows up. Johnny is excited, but then realizes the group is led by his old mob boss… and he’s been thinking of what got the world into all this trouble, and he realizes that people like mob bosses — and, indeed, like Johnny himself — are not the people to lead a new start. Solid work, nothing revelatory, but certainly displaying Gault’s professionalism.

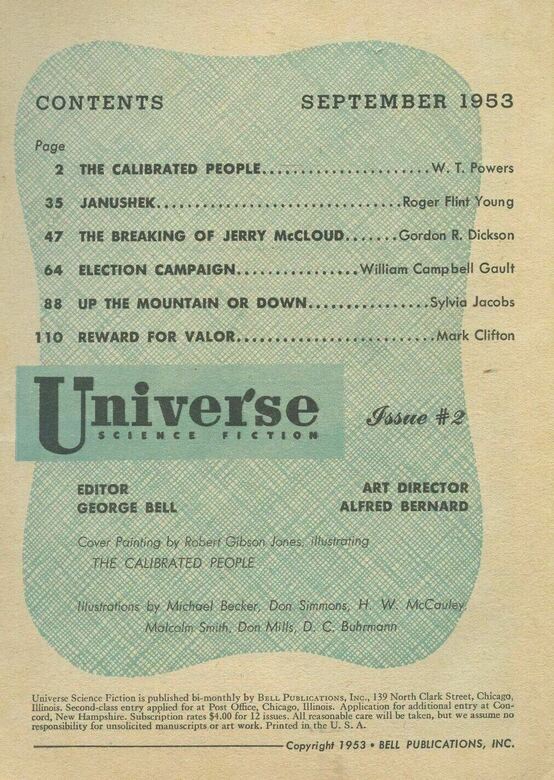

Table of Contents for Universe magazine, September 1953

I’ve discussed Sylvia Jacobs elsewhere — a writer oddly comparable to W. T. Powers, complete with doctorate, dabbling in Dianetics, and an SF career spanning roughly the same time frame, also beginning in Astounding and ending after an hiatus of a decade or so in Galaxy, and publishing about as many stories. “Up the Mountain or Down” opens as a new colonial administrator comes to a planet called (perhaps unwisely) Tonga. He is appalled at the relations between the two intelligent species on the planet — the reclusive Masters completely dominate the very human-like sholaths. But he is assured that the sholaths like it this way. He determines to confront the Masters, though travel to their mountain home is forbidden to humans. He sets out instead, with a party of sholaths, and his faithful dog.

It’s actually an intriguing setup, but the story does nothing with it. I was expecting a revelation about the Master/sholath relationship, and a comeuppance for the obviously misguided administrator. Instead, we get an instantaneous conversion by the administrator, who is convinced by his dog’s faithfulness that, I guess, that he was wrong after all (and, by implication, that the sholaths are to the Masters as dogs are to humans.) I mean, probably this is a plausible resolution, but it’s clumsily handled, and the story ends with a mini-lecture telling the readers what to think.

Finally, Mark Clifton, besides Dickson the best known of these writers (at least in SF), offers “Reward for Valor.” This one is told by a government official, inspecting a remote mine in the back woods (back desert?) of Mars. He hears a story of an ancient space pilot, now reduced to flying dilapidated under-maintained shuttles to the remoter places on Mars; and of this pilot’s various heroic exploits, all ignored due to political reasons, or the mendacity of sensation-seeking reporters.

And then there’s a mine explosion, and the shuttle pilot acts heroically yet again — even saving the life of a reporter — who instead is ready to credit the government official. And all this leads to the conclusion, one last flight on a rickety shuttle, and a baldly pointed moral about the true “reward for valor.” Like several of these stories, it is somewhat unconvincingly constructed with the clear plan of making its point, and the point is stated as much as shown, in case the readers miss it. But it does have a point, and a good one.

|

|

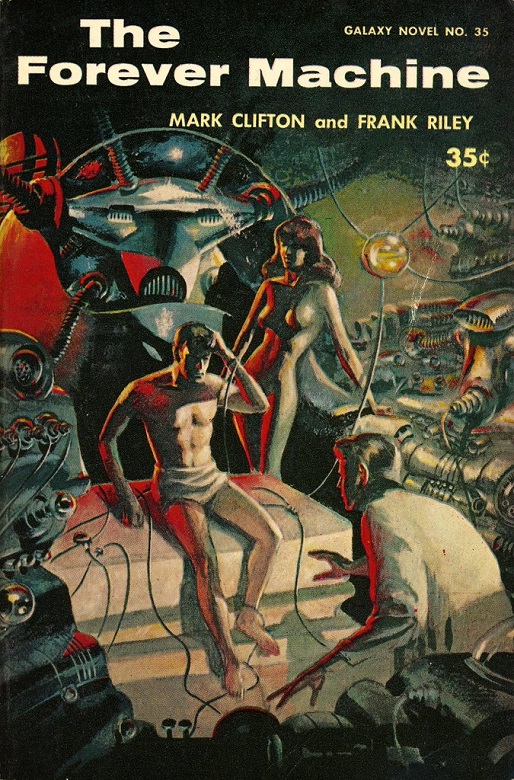

The Forever Machine (aka They’d Rather Be Right). Galaxy Novel 35, 1958. Cover by Wally Wood

Indeed, Mark Clifton these days is remembered mostly for his Hugo-winning collaboration with Frank Riley, They’d Rather be Right. But he was notably not a triumphalist sort of writer, and his best stories often have tragic endings, and dark themes. For particular examples, see “What Now, Little Man?” “What Have I Done?” and his last story before his untimely death, “Hang Head, Vandal.”

This really was a pretty interesting and ambitious magazine, though I don’t think any of the stories in this issue are lost classics. But they were all trying!

Rich Horton’s last article for us was an obituary for Alexei Panshin. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

That cover is boss!