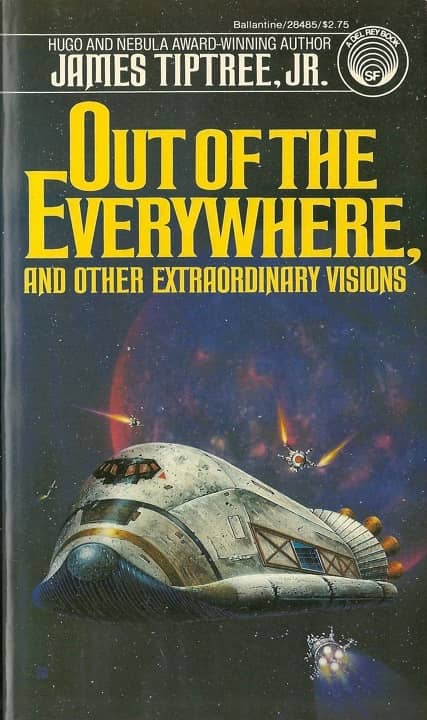

Vintage Treasures: Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary Visions by James Tiptree, Jr.

|

|

Out of the Everywhere (Del Rey, 1981). Cover by Rick Sternbach

Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary Visions was the last paperback Tiptree collection to appear in her lifetime, and the third from Del Rey. It includes two original novellas, “Out of the Everywhere” and “With Delicate Mad Hands,” the Hugo nominee “Time-Sharing Angel,” and one of the greatest science fiction stories of the 20th Century (very possibly the greatest), “The Screwfly Solution.”

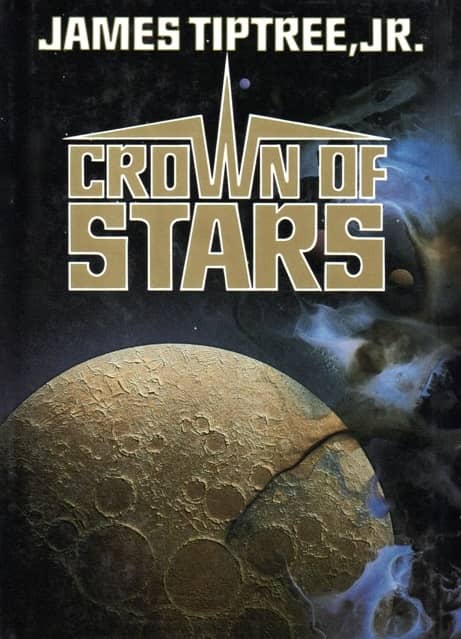

The first four stories in the collection, including “Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” and “The Screwfly Solution,” were published under the pseudonym Raccoona Sheldon (instead of Tiptree, also a pseudonym; the author’s real name was Alice Sheldon). These are the bulk of the Raccoona Sheldon tales, the only one not collected here is “Morality Meat,” which eventually appeared in Crown of Stars (1988). In his article “Where to Start with the Works of James Tiptree, Jr.” at Tor.com, Lee Mandelo argues that the Sheldon and Tiptree stories are fundamentally quite different.

|

|

|

|

|

|

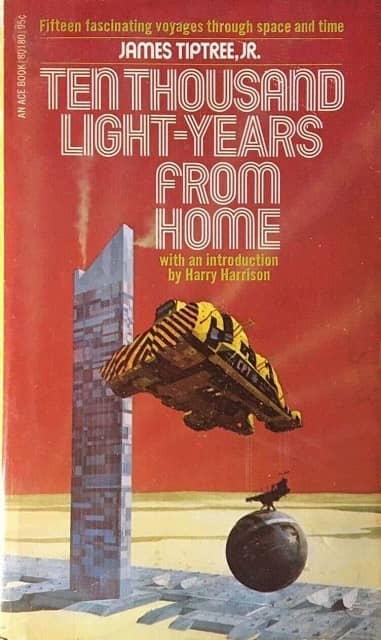

Some of Tiptree’s other collections: Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home (Ace Books, 1973, cover by Chris Foss),

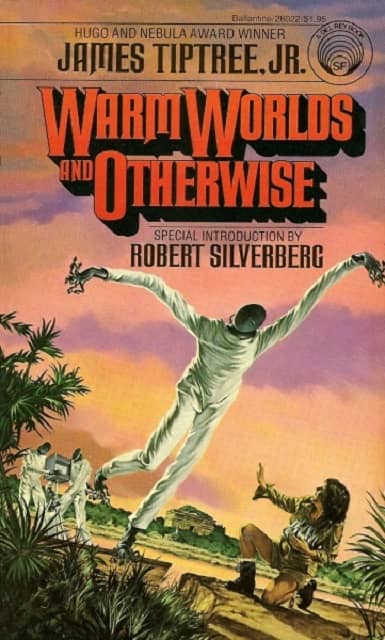

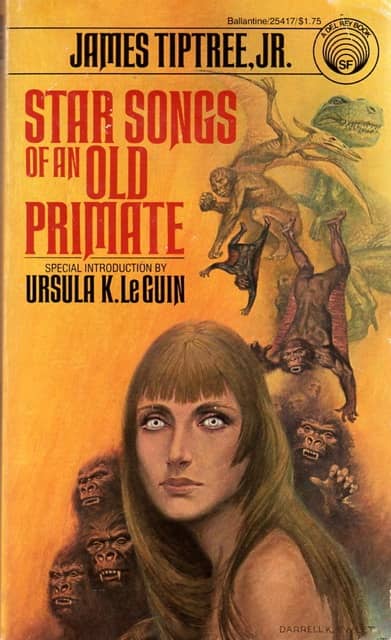

Warm Worlds and Otherwise (Del Rey, 1979, cover by Michael Herring), Star Songs of an Old Primate

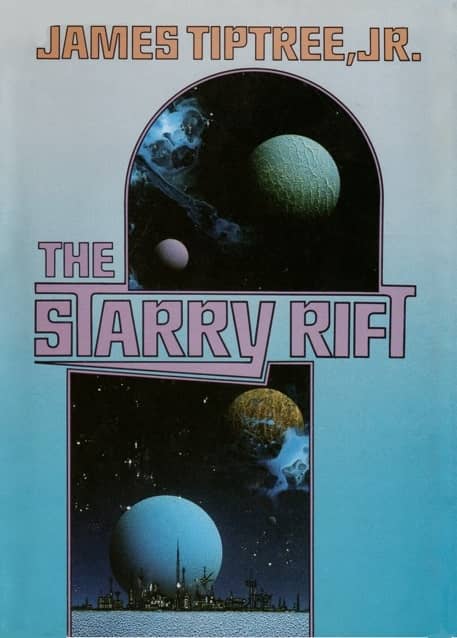

(Del Rey, 1978, Darrell K. Sweet), The Starry Rift (Tor, 1986, Dave Archer), Crown of Stars

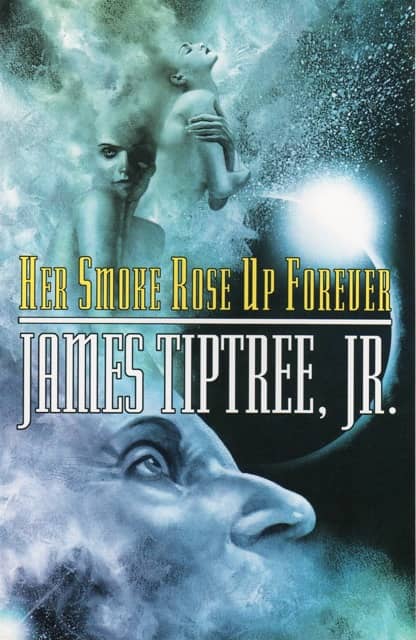

(Tor, 1988, Dave Archer), and Her Smoke Rose Up Forever (Tachyon Publications, 1990, John Picacio)

Here’s Lee:

“The Screwfly Solution” and “Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” are both Raccoona Sheldon stories. The first deals with the outbreak of a social turning where men have begun killing women at a genocidal rate, the twist being that it’s caused by alien bioengineering. The second, one of the most disturbing of Sheldon’s pieces, is about a young woman with a mental illness who believes herself to be in a safe, other, future world and escapes her hospital only to be brutally attacked as she tries to walk to the West.

These stories are unpleasant and cruel and unflinching; they’re rough reads, and represent well some of the anger and fear of women living under the systems of patriarchy — the brutality of it, too. The Tiptree stories, by contrast, are interested in exploring issues of gender and otherness from a more removed perspective.

T. Michael at Scurrilous Rag has a thoughtful look at several stories in Out of the Everywhere:

“The Screwfly Solution” — ★★★★★

Among the most enthralling, uncomfortable yet beautiful stories I’ve ever read, “The Screwfly Solution” is an epistolary tale of a pandemic sweeping the world, causing men (and only men) to become emotionally unstable and violent. We learn through letters and articles how the virus is causing uncontrollable violence of men almost exclusively against women. The world is in an uproar trying to understand this uncontrollable behavior, and much of the story is dedicated to faux-journal articles that capture the style of science writing perfectly, never misusing jargon or overdoing it.

The virus, it seems, doesn’t just make men blindly violent and murderous to women — they don’t turn into shambling zombies spuming at the mouth to kill — but causes them to rationalize their violence, taking the act of victim-blaming to its ultimate conclusion. “She was asking for it,” the men unanimously decry, slitting the throats of their loved ones for no reason whatsoever.

It’s a brilliant take-down of free will and human instinct that holds up surprisingly well to our current neuroscience. The unfolding of the means of transport for the virus, and what causes the murderous inclinations is worth discovering… A cute side note, I also love this story for featuring an accurate depiction of entomological fieldwork. The references to budworm research at the time (1977) accurately reflect the real scientific discussions in budworm science in the mid-to-late ’70s — discussions I used for my own graduate school research.

“With Delicate Mad Hands” — ★★★★☆

I can’t say “With Delicate Mad Hands” was a favorite of mine, but it’s nearly impossible to get it out of my head. What a vicious story.

CP was born with nearly impossible dreams: Orphaned — her mom died in childbirth and her dad, a politician, wanted nothing to do with it — and with a physical disability that earned her the nickname “Cold Pig,” CP’s goal is to travel the stars on long-term flights. She lives a quiet, depressing life, defined primarily by abuse and loneliness, with only the voice of her dreams to keep her company.

Dedicating her life to traveling among the stars, she finally earns a career in long-term space travel chiefly because of her appearance — her superiors think her pig-like nose will mean she’ll be subservient to her male peers, and won’t incite fights between men vying for her attention. Instead, she’ll simply serve as a sexual and physical slave to the crews she works with.

The voice in her head that pushed her towards this dream never leaves her, however, and eventually she works for a captain that pushes her too far… Somewhat miraculously, there is more to the voice than meets the eye, and Cold Pig’s story winds down with a lot of tragedy and love…

“We Who Stole the Dream” — ★★★☆☆

Another early Rift story, “We Who Stole the Dream” is another fantastical sci-fi adventure, of humans and aliens at war. The “We” of the title refers to the Joliani, a humanoid alien species enslaved by mankind as physical and sexual servants. The species collectively dream of escaping under the thumb of humanity’s (i.e., masculinity’s) gross self-obsession and need to f*** everything in sight — you know, for progress.

The Joliani, weak and abused (with some parallels to Native American subjugation), plot to fight back against their rapists, stealing a ship called the Dream. Using the coordinates for their homeworld — now entering into mythology due to its distance and time away — they travel back over generations to find the original Joliani… “…Dream” is touching, enthralling — depressing as ever — but it does remind me that I prefer Sheldon’s harder sci-fi.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

“Angel Fix” (Worlds of If, July-August 1974)

“Beaver Tears” (Galaxy, May 1976)

“Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” (Aurora: Beyond Equality, 1976)

“The Screwfly Solution” (Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, June 1977) — Hugo and Locus nominee, Nebula Award winner

“Time-Sharing Angel” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1977) — Hugo nominee

“We Who Stole the Dream” (Stellar #4: Science-Fiction Stories, 1978)

“Slow Music” (Interfaces, 1980)

“A Source of Innocent Merriment” (Universe 10, 1980)

“Out of the Everywhere”

“With Delicate Mad Hands”

Our recent coverage of James Tiptree includes:

Still Not Telling Us: “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” by James Tiptree, Jr. by Rich Horton (April 2022)

Vintage Treasures: Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home by James Tiptree, Jr. (2021)

Birthday Reviews: James Tiptree, Jr.’s “Please Don’t Play with the Time Machine” by Steven H Silver (2018)

Vintage Treasures: Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home by James Tiptree, Jr. (2018)

The Woman Who Was a Man Who Was a Woman: Alice Sheldon and James Tiptree Jr. by Thomas Parker (2015)

Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary Visions was published by Del Rey in December 1981. It is 276 pages, priced at $2.75. The cover is by Rick Sternbach. It has been out of print since the early 80s, though Gateway / Orion released a digital edition in 2016.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

It’s not as strong a collection overall as some of her others (it feels like one of those “odds and ends” anthologies that are tossed together sometimes after most of a writer’s best stuff has already been collected), but “Screwfly” is indeed great, “O My Sisters” is, among other things, a merciless critique of the idea that building imaginary sf worlds can accomplish anything in the real one, and “Slow Music” is for me the most emotionally affecting, most heartbreaking of all her stories; it almost left me in tears, so sad I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to reread it.

For my money, there is no one who can stand with Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree Jr., then or now.