Living in the Labyrinth: Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi

|

|

Piranesi (Bloomsbury paperback reprint, September 28, 2021)

I stopped apologizing about preferring old books over new ones a long time ago. One of the best things about reading, after all, is that it’s a kingdom over which you are an absolute sovereign. You alone can confer the Order of the Garter; only you can shout, “Off with their heads!” Nevertheless, while consistency is required of lesser beings, it need not be considered by monarchs, and so I decreed that the first book I read in 2022 would be Susanna Clarke’s fantasy Piranesi, which was published a little over a year ago, in September 2020. In this I was merely keeping a promise I made a few years ago here on Black Gate when I rhapsodized about Clarke’s previous novel, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. I said then that when Clarke finished her next book, I would line up to read it the day it was published. I think I came reasonably close; that I missed it by fifteen months I can always blame on COVID. Why the hell not? Clarke had said that her new novel would be set in the same magical Regency England of Jonathan Strange and would be a prequel to her first book. Chronic fatigue syndrome prevented her from completing that story, however (I fervently hope that it has only been temporarily set aside and not abandoned) and in its stead Clark produced Piranesi, a work a quarter the length of Jonathan Strange and very different in tone, but nevertheless bearing some strong affinities with the earlier work. Jonathan Strange is one of the greatest fantasy novels that I have ever read, and, within its smaller scope, the same is true of Piranesi. As Piranesi is relatively new and is, for much of its length, a puzzle that the narrator and reader are working out together, I will try to be more careful than usual in my description of its plot, but I can’t promise not to reveal anything significant. Let the reader beware. Piranesi — who narrates his own story — lives (almost) alone in an immense house of vast, empty halls and huge, winding staircases, peopled only by numberless statues (an Angel caught on a rose bush, a Woman carrying a beehive, a King with a model of a walled city in one hand), numberless because the house is more than simply enormous, more than just immense — it is, in fact, infinite. The House (which Piranesi always capitalizes, and which he thinks of as his benevolent parent and provider — he calls himself “the Beloved Child of the House”) is the world and the world is the House. Nothing exists outside of it except the sun and moon and stars that can be seen through the halls’ high windows. The ceilings of the upper halls are often hidden by clouds (which sometimes shed rain) and the lower levels of the House are completely inundated by water (“the Drowned Halls”), making a sea with tides that rise and fall and that Piranesi has meticulously recorded and can reliably predict (and which provide him with food in the form of fish and seaweed), and some of the halls and vestibules of the House are filled with flocks of birds that nest in the arms of the statues, many of which are of gigantic size.

Susanna Clarke

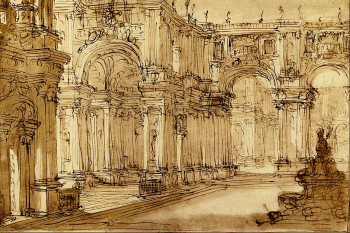

Piranesi is only “almost” alone in his world because he is periodically visited by his only friend, the short-tempered and peremptory man whom Piranesi calls the Other, who gives him scientific tasks of observation and measurement to perform; both men believe this will help the Other in his search for the long-lost “Great and Secret Knowledge,” a knowledge which will grant the Other tremendous power. Aside from the services he performs for the Other, Piranesi fills his days with fishing, exploring the House, writing, and lovingly tending thirteen skeletons that he has found in various halls. These remains have led him to deduce that all humanity once consisted of sixteen people — the thirteen dead, himself, the Other, and number Sixteen, the unknown person that he is writing for. Not much will be given away if I complete my summary by quoting the publisher’s press release: “Piranesi records his findings in his journal. Then messages begin to appear; all is not what it seems. A terrible truth unravels as evidence emerges of another person and perhaps even another world outside the House’s walls.” That slow unveiling of the truth of Piranesi’s world comprises the main action of the novel, but engaging as the story is (and it’s a real page-turner), Piranesi is most memorable in the resonant atmosphere that Clarke builds around its extraordinary setting, and much of that atmosphere is dependent on what has gone before, in history and in literature. As the halls of the House echo with Piranesi’s footsteps, so Piranesi resounds with allusions and intimations that fill the frame of the story almost to bursting, one of the first and most important being the name of the protagonist himself. Piranesi knows that that isn’t his now-forgotten real name; instead, it’s a name given to him by the Other, perhaps (he sometimes suspects) in mockery. Piranesi doesn’t know of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who was an eighteenth century Italian artist and architect, best known for his elaborate etchings of imaginary and mazelike prisons. Knowing that (and I had to look it up, not being up on eighteenth century Italian architects) will immediately give you a clue as to our Piranesi’s real situation.

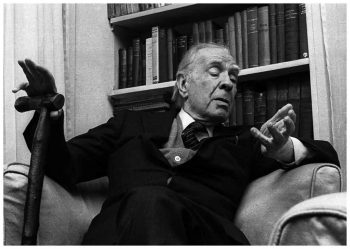

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

One of the most captivating things about Piranesi is that it functions as a literary echo chamber, and reading it will make you think of many other books and authors, most especially C.S. Lewis. Clarke begins the novel with a quotation from The Magician’s Nephew, and she alludes to the Narnia books in several other places. (At one point the statue of a faun makes Piranesi think of a little girl talking to such a creature in a snowy wood, an image that he does not understand but that we may recognize as Lucy meeting Mr. Tumnus in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, after she has passed through the portal from our world to Narnia.) Aside from the references to Lewis, the vast, self-contained world-structure in which Piranesi lives (and the Gothic trappings of his predicament) inevitably bring Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books to mind, as it does many similar stories — Lovecraft’s “The Outsider,” John Collier’s “Evening Primrose,” and the novels The Sundial and Castaway by Shirley Jackson and James Gould Cozzens, respectively. Moving to a loftier plane, Clarke’s hints that each of the House’s statues correspond to a reality in another world may be an oblique reference to Plato and his ideal forms. In addition to Lewis and these others, the author that Piranesi most strongly evokes is the Argentinian fabulist, Jorge Luis Borges, who wrote of labyrinths of Gnostic knowledge (Labyrinths being the title of his most celebrated book), and the search for the Great and Secret Knowledge in the maze of the House proves to be vital to Piranesi’s plot. The House is frequently explicitly described as a labyrinth, and one of its central rooms (it turns out to be the key room of the House, in fact) is peopled by colossal statues of minotaurs, the fabled monster of Greek myth that Theseus tracked to the center of the labyrinth where it dwelt.

Jorge Luis Borges

Full as the book is of them, none of these references, echoes, or allusions are overbearing or egregious. They never mute Clarke’s own voice or blunt her individual vision, or divert us from working out her purpose; rather she has used them to embroider and enrich a unique world that is very much her own. Like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Piranesi’s plot turns out to be driven by a conflict between two egotistic mages, and like the earlier book, it is also deeply concerned with the ways we shape and are shaped by the worlds that we construct. How do we get into those worlds and how do we get out of them, and which is the better choice? The problem isn’t made any easier when we recognize that the most baffling mazes are those which we fashion for ourselves. Fantasy though it is, Piranesi is grounded in the bedrock questions of living that all of us face every day. While Piranesi’s concerns are not unlike those of Clarke’s first novel, it is almost completely lacking in the wit and humor which so enlivened Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. If Piranesi were as long as Jonathan Strange, I might feel this to be a fault, but Piranesi is a much shorter, swifter-moving and less discursive book, and it’s over almost before you notice the difference. The more sober tone is completely appropriate to the story, and I don’t think the absence of lighter moments is a mark against it.

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell

What Piranesi lacks in high spirits it more than makes up for in depth of feeling; it’s a profoundly meditative, melancholy work suffused with the amber light of memory and permeated with a mood of loneliness and loss. In the end, more than sweet, lost Piranesi himself and his dilemmas and his adventures, more than the book’s elegant allusions and elaborate riddles, what I will carry away with me is Piranesi’s world itself, with its silent, imperturbable, innumerable statues, its marble staircases ascending into the clouds and descending into the waters, its echoing, bird-haunted, tide-drenched halls stretching into infinity. It is a beautiful, serene, sinister, strange, and ultimately inexplicable place that will stay with me forever. From this I begin to divine a principle, which is confirmed when I contemplate all the other great fantasy lands of literature that I have visited, from Utterbol to Middle-earth to Earthsea to Elfland to the world of the Bridge.

Fantasy of a Palace by Giovanni Battista Piranesi

The principle might be stated like this: the created world is the foundational miracle, more mysterious, more amazing, more moving, and ultimately more significant than anything that actually happens in it. I suspect that this is true even of the world outside the covers of books, and the unique value of fantasy may lie precisely in its power to help us recognize this truth. I think that perhaps Susannah Clarke agrees; at least it is possible to read Piranesi as an illustration of this principle. But please don’t take my word for it. Read this wonderful book for yourself and when you are done you will be able to say with Piranesi and with me, “In my mind are all the tides, their seasons, their ebbs and their flows. In my mind are all the halls, the endless procession of them, the intricate pathways.” When you have turned the last page of Piranesi, you will possess the Great and Secret Knowledge that only a supreme work of fantasy can grant; then you too will be a Beloved Child of the House.Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Indecent Exposure: The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

I, too, thought of the Gormenghast novels by Mervyn Peake when reading Piranesi (which, curiously, was also my first book of 2022), along with other “architectural” fantasies like Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland or James Stoddard’s The High House. In the end, it was not so much the infinite expanse of the House that stayed with me, but the idea of entrance/exit and the joys of having both. So, the metaphor of Literature was where I found myself enjoying the idea of characters like Sixteen escaping from the “real” world into the privacy/fantasy/exuberant creativity (a statue of 2 kings playing chess!) of every reader’s very own book-fueled imagination.

Yes, I was also getting Gormenghast — it almost felt like Gormenghast as written by George MacDonald.

Well done, Mr. Parker – an insightful review, and just the right length for its subject, like the brilliant “Piranesi” itself. I read it at about this time last year, and then spent 2021 giving copies to friends and relations whenever the opportunity arose.

After a second reading this book still does little for me. Too deliberate in its structure and scenarios such that I could not immerse myself into this world of Clarke’s creation (which felt like her attempt to impress reviewers and peers rather than crafting something for the reader). And Piranesi himself felt, for much of the novel, very flat and bland. I was ready to order her earlier work but decided against it and I won’t be purchasing any future efforts by Clarke. I’ll stick to the authors I know will fulfil me as a reader, like the other Clarke (Arthur C.) and Clark (Ashton Smith).

Mark, I would recommend Jonathan Strange as strongly as I can even though Piranesi wasn’t your cup of tea. It’s a much more wide-ranging book with a large and lively cast of characters.

When I first read Piranesi, I commented that it “confounds the reader’s expectations in the best possible ways.” Every time I thought I knew what was going on, Clarke would throw in a twist to explain it in a different, and better, way.

Piranesi is indeed a great novel. I have been meaning to write about it for at least a year. It is a truly beautiful novel, about an oddly beautiful place …

And, yes, Mark, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is much different — and also great. If you didn’t like Piranesi you may still love JS&MN.

Thomas — Clarke has completed another novel, and I believe that one is in the JS&MN universe. I don’t know if it’s the prequel she had been working on before her health issues intervened. I believe the new novel is due fairly soon.

There are also, of course, some short stories in that universe, in her Ladies of Grace Adieu collection.

Also, it is a damn shame, but wholly understandable, that it lost the Hugo award to Martha Wells’ Network Effect. Don’t get me wrong — I really enjoyed Network Effect, and indeed all the Murderbot stories. They are great fun. But Piranesi is at another level.

To be sure, the Hugo is a popular award, by design, and Network Effect is undoubtedly (and deservedly) very popular.

Network Effect, of course, also won the Nebula. People used to say the Nebula was the more “literary”, less “popular”, of the two most prominent SF awards. If that was ever true — and, actually, I think it was SLIGHTLY true decades ago — it isn’t now.

That’s GREAT news about the upcoming JS&MN universe book, Rich. I’ll be there the day it’s published…or withing the first fifteen months, anyway…

In the meantime, maybe I’ll get around to the Ladies of Grace Adieu, which I have but haven’t gotten around to yet.