The Ordinary is Ephemeral: Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, H.P. Lovecraft, and the Battle Against Modernism

Weird Tales of Modernity: The Ephemerality of the Ordinary in the Stories of Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, and H.P. Lovecraft

Weird Tales of Modernity: The Ephemerality of the Ordinary in the Stories of Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, and H.P. Lovecraft

Jason Ray Carney

McFarland & Company (205 pages, $39.95 in paperback/$23.99 digital, July 26, 2019)

Jason Carney’s thesis in Weird Tales of Modernity is that, in their reaction to modernism, the artistic and literary movement that upended culture as it had been accepted in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, the Weird Tales Three — Howard, Smith, and Lovecraft — turned modernism on its head with innovations they introduced in their fiction. Make no mistake: the word thesis here is apt. Weird Tales of Modernity is a formal dissertation. Making use as it does of academic jargon, the book will not be for every reader.

Straightaway, for example, Carney introduces us to the term ekphrastic to make clear what the Weird Tales Three were expressing. Ekphrasis is the representation in language of a work of art. Any of us can do this; go ahead and write your own personal, detailed description of Cthulhu or explore how you react to Frank Frazetta’s artwork. Ekphrasis “acts as an organizing principle in poetry and fiction, making explicit the connection between art, storytelling, and life.” This definition is from Patrick Smith’s guest blog on the website Interesting Literature. Smith quotes Michael Trussler in defining ekphrasis as “a kind of ontological mixture that signals a world beyond the confines of the text.”

There we have it: ekphrasis “signals a world beyond the confines of the text.” We are now in Lovecraft’s frightening, paranoid, awakened world of the Cthulhu mythology — alive beyond the confines of the text — and Clark Ashton Smith’s Averoigne and Poseidonis, and Robert E. Howard’s brutal Valusia and Hyborian Age. As Carney says early in Weird Tales of Modernity, “When a literary artist, like [Clark Ashton] Smith, artistically describes or fictionalizes a work of art by transforming it into an unreal echo or shadow of the actual, that is ekphrasis.”

Carney devotes an early chapter to the history of Weird Tales and then two chapters each to the three authors of his study, introducing them and then exploring their artistic innovations. He begins his study with an examination of what he terms pulp ekphrasis. “In several of their enduring works,” he says,

Lovecraft, Howard, and Smith engage in a form of artistically inflected criticism termed ekphrasis. They do so by fictionalizing modernism, transforming the real artistic movement into an unreal shadow modernism, a strategic distortion of actual modernism. After many creative iterations honed over several stories — e.g., Pickman’s demented art, Malygris’s sorcery, the fell mirrors of Tuzun Thune — this shadow modernism becomes an inhuman technology that, functioning like a cognitive prosthesis in the virtual world of fiction, thereby reveals the secret truth of history: history is a cruelly accelerating process of deformation. The ordinary is ephemeral. History is an interplay of form and formlessness with formlessness terminally ascendant.

The ordinary is ephemeral. Lovecraft, Smith, and Howard were keenly aware of this truth and reacted to it in their fiction while other Weird Tales writers were moving right along in the modern world, writing their stories of scientifiction, offering narratives of ominous cults and mad scientists (with at least one nude woman per story), or revisiting the tropes of Victorian horrors.

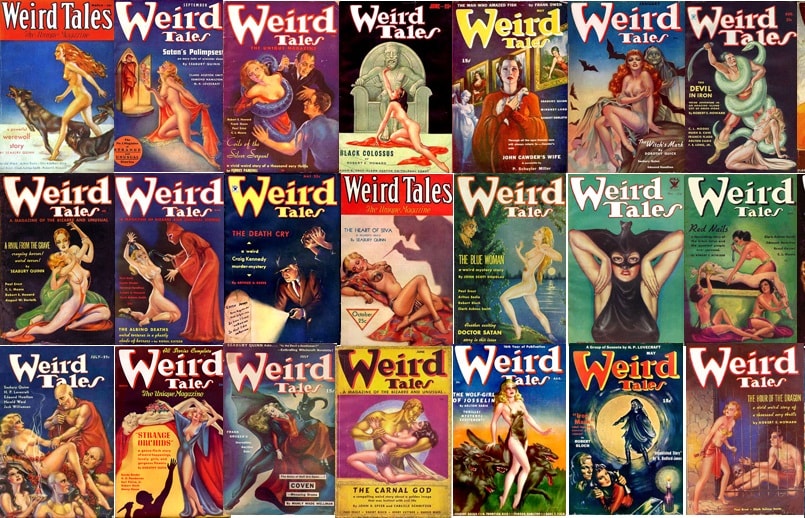

A panorama of Weird Tales. Covers by Margaret Brundage

We all are familiar with Howard’s and Lovecraft’s discomfort with the modern age, as they called it. And Clark Ashton Smith, after initially keeping company with the modernists (he was published alongside Yeats and Pound in the third issue of the famous little magazine Poetry, “a primary site of academic modernism’s emergence”), was very soon out of step with the new aesthetic. He did, however, explore “his uneasy feelings linked to actual modernist art by fictionalizing and distorting it, as if by a funhouse mirror, thereby rendering an unreal shadow modernism.” He used “modernist art to produce something like knowledge, a sinister intimation that the future, as its recognizable forms deform, will grow increasingly strange.”

The modernism that the Weird Tales Three reacted against (while making use of it in some of their own fiction) was a reaction to and an advocate of the enormous changes occurring in the Western world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — industrial, philosophical, artistic, and literary. This is the machine age, and the era of Eliot’s The Wasteland and Picasso and Braque’s cubism, of atonal music in the orchestral hall, of the infamous New York Armory Show of 1913 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which caused such a disturbance at its premiere the same year. It is scientific. It is concrete. It is brutalist architecture. It is “triumphant” form enduring forever.

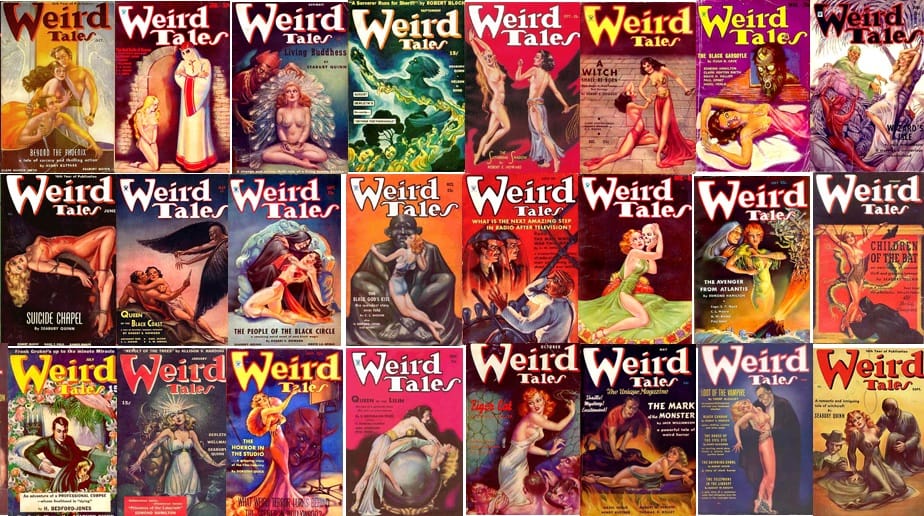

More Brundage Weird Tales covers

In contrast, the pulp ekphrasist — Lovecraft, Smith, Howard — “focuses on formlessness.” Howard’s ancient, decaying cities in ruins. Lovecraft’s Erich Zann, “a modernist who transgresses and also a traditional artist who maintains the unknowledge of the ephemerality of the ordinary.” Smith’s Ubbo-Sathla, a formless mass that reposes “amid the slime and the vapors. Headless, without organs or members, it sloughed from its oozy sides, in a slow, ceaseless wave.” As Carney makes clear:

Smith, Howard, and Lovecraft go beyond unsophisticated repudiation in order to engage in ekphrasis and so artistically project onto a distorted and ultimately fictional shadow modernism their fears and hatreds concomitant with their identification as stewards of a threatened European aesthetic tradition.

Many of us, perhaps most of us, have long considered the “Weird Tales three” as a handy construction of L. Sprague de Camp’s. Why he settled on these three — or even settled on three rather than two or four or five — remains a mystery to me. I surmise it’s because he saw in them an extension of the famous Lovecraft circle expanded to include two more successful Weird Tales writers (and correspondents) who shared concepts and ideas, including them in each other’s stories.

Dr. Jason Carney

Carney’s use of the phrase now supersedes de Camp’s rather arbitrary representation by placing the three on solid ground. Unlike other writers who appeared in Weird Tales, these three writers did indeed react personally and artistically to the “threat” of modernism, comprehending the new worldview even while artistically defying it:

They are fundamentally pulp writers who eschewed the intellectualist literary trends of their day to concentrate on stirring their readers with wonder, horror, and excitement; accordingly, they were ambitious literary artists who took their pulp fiction craft seriously and encoded thoughtful philosophical speculations in their fiction. Put another way, they were literary artists who had no faith in literary immortality, who viewed their work soberly, as ephemera, as pulp, as decaying plant matter.

I had not conceived of these authors and their time in this way until I read Weird Tales of Modernity. Jason Carney has put Lovecraft, Smith, and Howard in a context as self-evident as it is eye-opening, as artists in a period of artistic vitality reacting to that modern tidal wave of vitality by methods that, in retrospect, seem damned heroic and even more remarkable than they have been given credit for. Jason Ray Carney has provided great insight into their legacy and, for me personally, has widened my appreciation of their accomplishments.

David C. Smith (born August 10, 1952, in Youngstown, Ohio) is an editor, writer, and author, recently retired after working nearly thirty years as a medical editor and managing editor of a peer-reviewed orthopaedic journal. He is the author of twenty-six novels and collections and of many short stories and articles, as well as of a post-secondary English grammar textbook.

David C. Smith (born August 10, 1952, in Youngstown, Ohio) is an editor, writer, and author, recently retired after working nearly thirty years as a medical editor and managing editor of a peer-reviewed orthopaedic journal. He is the author of twenty-six novels and collections and of many short stories and articles, as well as of a post-secondary English grammar textbook.

He loves writing and editing and the English language and is available as a freelance editor. Smith lives in Palatine, Illinois, with his wife, Janine, and their daughter, Lily, and their cats, Rosebud and Corabelle. He is on the web at blog.davidcsmith.net and on Wikipedia at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ David_C._Smith_(author).

His last article for Black Gate was a review of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery by Brian Murphy

Wow! This is one of the most amazing articles I’ve ever read at BLACK GATE, and I’ve been here a long time. This book sounds fascinating, so thanks for bringing it to everyone’s attention.

A few thoughts:

– Smith, Lovecraft, and Howard, in rejecting modernism and the contemporary expectations of writers, in choosing to express their ideas and themes in “theater of pulp”–all of this makes these guys PUNK ROCK about fifty years before punk rock was even invented.

– Smith’s work was often cited a throwback to the Romantics such as Byron and Shelley–for good reason, as he was indeed a Romantic, but his dark sensibilities made him more like Poe than Byron. Smith’s rejection of the contemporary world mirrored Howard’s rejection of the contemporary world–both men found far more freedom in the depths of history and legend than in the modern world.

– Back in 1818 Shelley’s famous poem “Ozymandias” touched on the same theme as cosmic horror would a century later–the idea that everything is ephemeral and therefore insignificant in the face of the formless universe–nothing lasts, not even the monuments to kinds and gods, and certainly not anything ordinary. Here it is:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear —

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

(Uh, “kings and gods”, not “kinds”…)

What a great essay. I doubt that I will read Carney’s book – too much like the day job – but I’m glad to have read your reification of his ideas. Thanks.

So all those ruined temples and sinister deities are a distorted (and transmogrified) reflection of modern culture, specifically the arts? I can buy that, but would wonder to what extent the process was a conscious one. What’s interesting is how the attitude of each author differs. Lovecraft’s characters are terrified, Howard’s characters are primitives who challenge it, whereas Smith’s characters are mostly sorcerers and wizards who embrace it – ie, Smith seems to be both repulsed and fascinated by the worlds he so lovingly creates.

I’m ordering a copy today. Carney has articulated an idea I’ve pondered for some time, that Howard, Lovecraft, and Smith sought to express the loss of humanity in a flattening, alienating age.

At the first Worldcon I attended (BucConeer 1998, Baltimore), I went to a panel discussion about the “battle” between the pulps and the Modernists, mainly out of bafflement that the pulp writers knew or cared about the poetry of Eliot and Pound. The panel turned into a delicious academic mud-fight between Michael Swanwick (pro-battle) and John Kessel (anti-battle), which had us hootin’ and hollerin’ in our seats. And which led me to Readercon in subsequent years for more of the same intellectual knife-fighting.

Alas, I did not see a real basis for the “pro-battle” side of the argument, but I must admit that Dr. Carney’s thesis goes a long way towards making it. I may need to investigate a university library to see if I can learn more from him.

“At the first Worldcon I attended (BucConeer 1998, Baltimore), I went to a panel discussion about the “battle” between the pulps and the Modernists…”

That’s awesome! Thanks for sharing that memory, Eugene.

[…] of unusual angles, Black Gate has a short but perceptive review of the new academic book Weird Tales of Modernity (2019). The book’s author was also interviewed at length recently, on episode #140 of The […]

Great post. Thanks for waking us aware of this. Kudos to Jason Carney for demonstrating the serious crafting behind the pulps.

In CAS’s The Hunter From Beyond (1932) he explicitly calls out Baudelaire (the weird poet who coined the term “Modernity”).