Fantasia 2016, Day 15: Ghosts and Djinns (Lace Crater and Under the Shadow)

At 7:30 PM on Thursday, July 28, I was in a seat in the De Sève Theatre waiting to see a screening of an American independent horror-comedy called Lace Crater, about a woman who catches a venereal disease from a ghost. After that I’d cross the street to the Hall theatre for a showing of the Iranian horror movie Under the Shadow. I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect from either film, which from experience I knew was often the best way to come to a screening at Fantasia. I was pondering this when the lights went down and Adam Kritzer, producer of Lace Crater, was introduced to the crowd. He thanked us for coming, and urged all of us in the audience to turn to our neighbours, whether we knew them or not, and say whether we believed in ghosts. There was an aisle to my left. I glanced to my right. The man beside me shrugged. “Not particularly,” he said in French. “Same here,” I replied.

At 7:30 PM on Thursday, July 28, I was in a seat in the De Sève Theatre waiting to see a screening of an American independent horror-comedy called Lace Crater, about a woman who catches a venereal disease from a ghost. After that I’d cross the street to the Hall theatre for a showing of the Iranian horror movie Under the Shadow. I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect from either film, which from experience I knew was often the best way to come to a screening at Fantasia. I was pondering this when the lights went down and Adam Kritzer, producer of Lace Crater, was introduced to the crowd. He thanked us for coming, and urged all of us in the audience to turn to our neighbours, whether we knew them or not, and say whether we believed in ghosts. There was an aisle to my left. I glanced to my right. The man beside me shrugged. “Not particularly,” he said in French. “Same here,” I replied.

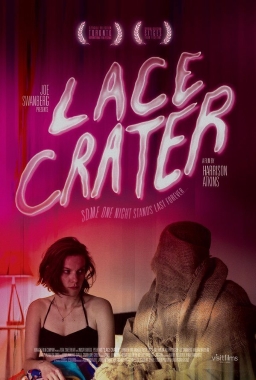

One’s personal beliefs aside, Lace Crater is an intriguing film. Written and directed by Harrison Atkins, it starts with a group of young friends who go to a house in the Hamptons, owned by the family of Andrew (Andrew Ryder), one of the bunch. Low-key sexual banter ensues. One of the women, Ruth (Lindsay Burdge, of The Midnight Swim and The Invitation), ends up sleeping alone in a guest house, which Andrew has warned her may be haunted. It is, by a ghost named Michael (Peter Vack). Michael, clad in burlap wrappings, isn’t very scary. He and Ruth end up talking, and connecting. And sleeping together. But back in the city, Ruth finds her one-night stand has consequences. She’s caught something that looks a lot like an STD from Michael, and it makes her increasingly erratic, putting increasing strain on the small network of her friends. Will she find a cure? Or will she have to face Michael again?

Kritzer’s introduction had promised a sexy ghost story, which I assume now was a joke; Lace Crater is, when you get down to it, a movie about a woman who has a one-night stand and contracts a nasty social disease. Which doesn’t strike me as the most sexually charged story in the world. On the other hand, there’s an engaging low-key aspect to the whole affair, a sense of normality, of mundanity, that reasserts itself through the whole tale. It’s a movie that resolutely refuses to let its supernatural aspects dominate.

Standard genre tropes are mostly avoided, then. Instead there’s a somewhat mumblecore-y story about young people in New York and their romantic lives and the complications therein. It’s not a horror story, or at least not in supernatural terms. It’s perhaps closer to a romantic comedy with horror elements, but even there it maintains a straight-faced sensibility. Comic scenes aren’t pushed, aren’t played for laughs. When Ruth tries to find out about ghost STDs on Google, it’s played straight. I’ve used the phrase “low-key” a couple of times so far, and I have to use it again here. But does that approach work? Or is the story too muted, the drama too minimal?

Standard genre tropes are mostly avoided, then. Instead there’s a somewhat mumblecore-y story about young people in New York and their romantic lives and the complications therein. It’s not a horror story, or at least not in supernatural terms. It’s perhaps closer to a romantic comedy with horror elements, but even there it maintains a straight-faced sensibility. Comic scenes aren’t pushed, aren’t played for laughs. When Ruth tries to find out about ghost STDs on Google, it’s played straight. I’ve used the phrase “low-key” a couple of times so far, and I have to use it again here. But does that approach work? Or is the story too muted, the drama too minimal?

I’m genuinely not sure. I do think the film does a good job of catching the sense of the web of relationships among a network of friends. But then those friends are, I found, underdeveloped. There’s not much of a sense of their histories or how they live their lives; so what drew them together in the first place, for example, is unclear. I would go a step further and say that as individuals, largely seen through Ruth’s eyes, they’re largely unsympathetic characters. We don’t get much of a reason to care about any of them. To an extent this also is what the movie’s about, Ruth being divided from her friends; but, again, it’s difficult to feel terribly invested in this aspect of the story.

The acting is fine, particularly Burdge’s Ruth and Vack’s Michael. The latter in particular does a good job acting with his face covered, using just voice and movement. The camerawork of the film tends to focus on character, with lots of close handheld shots, and the actors show some good restraint (and go big when they need to). In general the visual style’s very involving, creating an intimate feel that lets character emerge from well-chosen moments that feel like they’re caught almost by accident.

The acting is fine, particularly Burdge’s Ruth and Vack’s Michael. The latter in particular does a good job acting with his face covered, using just voice and movement. The camerawork of the film tends to focus on character, with lots of close handheld shots, and the actors show some good restraint (and go big when they need to). In general the visual style’s very involving, creating an intimate feel that lets character emerge from well-chosen moments that feel like they’re caught almost by accident.

But if the visual style is effective, I’m not sure the drama and story match it. The dialogue feels very loose. It’s difficult for me to find significant themes emerging from the writing. Individual scenes are often fine — Ruth’s dialogues with Michael in particular — but the assemblage feels like less than the sum of its parts. On the other hand, the supernatural elements fit in quite well. If the film’s held together by a sensibility as much as by plot, then the sensibility at least is coherent and incorporates the ghostly aspect quite well.

As I said, I’m genuinely not sure whether it all works or not. I suspect not, as it didn’t move me much one way or another. It’s an original take on a ghost story, but it’s not compelling. Very watchable, and keeps the interest moment to moment, but doesn’t build, doesn’t feel all of a piece. The end felt less touching or enigmatic than simply a conclusion, not inevitable so much as the place where things had to go because there wasn’t enough story logic to drive the film anywhere else. Like so much else here, it’s not a poor choice so much as it is unremarkable.

After the movie, Kritzer came back to take questions. The first one was how does a producer pitch a movie like this to investors? He answered by saying that he as a producer isn’t interested in what makes a film alien but in what makes it human. He pitched Lace Crater as ‘The Scarlet Letter with ghost STDs,’ and as being about slut shaming (which I did not see in the final film, but there you go). Questions about the ending led him to talk about how the script was structured; rather than create a full script, director Harrison Atkins (who Kritzer had earlier described as like a force of nature) created a a treatment and incorporated a lot of improvisation from his cast. There were three or four beats the movie might have ended on, Kritzer said.

After the movie, Kritzer came back to take questions. The first one was how does a producer pitch a movie like this to investors? He answered by saying that he as a producer isn’t interested in what makes a film alien but in what makes it human. He pitched Lace Crater as ‘The Scarlet Letter with ghost STDs,’ and as being about slut shaming (which I did not see in the final film, but there you go). Questions about the ending led him to talk about how the script was structured; rather than create a full script, director Harrison Atkins (who Kritzer had earlier described as like a force of nature) created a a treatment and incorporated a lot of improvisation from his cast. There were three or four beats the movie might have ended on, Kritzer said.

Asked about the name of the film (not referred to in the script), he said that Atkins as an artist was deeply into semiotics, and symbolic abstract choices; the title wasn’t meant to be literal, but a two-word poem. The lace, he said, was meant to call up images of texture and femininity, while the crater referred to Ruth and her absence. Asked how much improvisation made it into the film, he said a lot — the original treatment was about 35 or 40 pages, some of which were pages of monologues that were ultimately scrapped. He expressed his appreciation for Atkins’ command of the medium, and said that the incorporation of improvisation into Atkins’ process allowed the creation of moments of truth. Asked whether the film was meant to be read as discussing addiction, Kritzer said that it was an interesting question, and that the film broadly had to do with stigma. Asked about the budget, he said the film cost well under $100,000 to make; in trying to raise money they were offered a bad contract that would have meant turning over a lot of rights, but were advised to leave it, and swiftly got a better deal. Finally, asked if he himself believed in ghosts, he said he absolutely believes in a spiritually charged reality.

Which was a good note on which to go watch Under the Shadow. The feature was preceded by a short, “Other People’s Heads,” directed by Stephen Winterhalter. It’s an odd symbolic or perhaps allegorical drama about a room of people watching as, one by one, prisoners are led to a guillotine. The chopped-off heads, still living, are then taken into a back room by an attendant. But is he beginning to feel a spark of rebellion? The colours of the movie are lush, and it’s always pleasurable to watch. At 13 minutes, though, it’s betwixt and between — too long for the too-little explanation we get of what we’re seeing, and too short to build up drama without a bit more explicit dialogue. It’s a nice attempt to try to tell a story in pictures, but I found myself unclear on the basic relationship of the people on screen, and indeed what it was I was seeing.

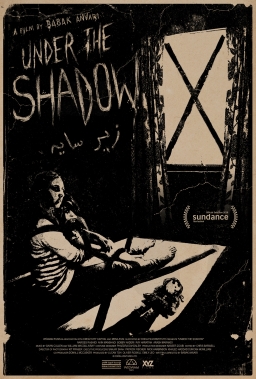

Under the Shadow was more rewarding. Written and directed by Babak Anvari, it’s set in Tehran in 1988, near the end of the Iran-Iraq war. We follow a young wife and mother, Shideh (Narges Rashidi), who is turned down in her attempt to enter medical school because she’s been too politically active during the revolution. At home, her husband Iraj (Bobby Nadari) is relatively understanding but also limited; meanwhile, her apartment building’s home to people relocated due to the war, and her daughter Dorsa (Avin Manshadi) has met a strange new child. Then Shideh’s husband, a doctor, is called to the front to fulfill his military service. And then a missile lands on the apartment building, killing one man but not exploding. Only — was there something else aboard the missile? Dorsa speaks about a djinn, a mysterious lady who talks to her. The tension begins to ramp up as internal and external threats grow more fearsome.

Under the Shadow was more rewarding. Written and directed by Babak Anvari, it’s set in Tehran in 1988, near the end of the Iran-Iraq war. We follow a young wife and mother, Shideh (Narges Rashidi), who is turned down in her attempt to enter medical school because she’s been too politically active during the revolution. At home, her husband Iraj (Bobby Nadari) is relatively understanding but also limited; meanwhile, her apartment building’s home to people relocated due to the war, and her daughter Dorsa (Avin Manshadi) has met a strange new child. Then Shideh’s husband, a doctor, is called to the front to fulfill his military service. And then a missile lands on the apartment building, killing one man but not exploding. Only — was there something else aboard the missile? Dorsa speaks about a djinn, a mysterious lady who talks to her. The tension begins to ramp up as internal and external threats grow more fearsome.

This is an incredibly effective horror-fantasy film. The monster’s well-imagined; built up through most of the movie unseen, it finally emerges at the climax and then is done wonderfully, giving us a glimpse of another world. The structure of the horror story is built up carefully, using the time-honoured technique of the child who has seen more than the adults realise.

At the same time, the movie’s also a strong depiction of a specific time and place and society. The tension of war comes across strongly. So does the nature of the environment, the community of the building and relations between neighbours, as well as the larger social structures shaping Shideh’s life. We see her exercising to a bootleg aerobics tape, see how it must be hidden, see how in a moment it can become a terrible danger if the wrong eyes see it. We see the kinds of compromises Shideh has to make, as well as the everyday ways she and her family live while caught in the middle of a war.

Mostly, we get something of a sense of what it is to be a woman in 1988 Iran. This is a thoroughly feminist work; it’s no accident that it opens with a woman being told by a man that she won’t be allowed to study medicine, follows the woman as the main character, and concerns itself deeply with the relationship between her and her daughter. There is much here about dress codes, about Shideh’s contempt for the need to wear a hijab whenever she leaves her home and about the force her society brings to bear on her for doing as she’s expected. About the everyday shadow over her life.

Subtextually Shideh’s conflict with her society is reflected in the nature of the horror she faces. The djinn wants to take her daughter from her, to make her live in its world. Which implies what’s at stake not just metaphysically but ideologically. When we see the djinn near the end — a djinn Dorsa’s described as a woman — we get at first just a disquieting glimpse of someone in a chador. That image later expands, the cloth becoming a kind of labyrinth Shideh must negotiate. Dorsa’s life is at stake, her future; the djinn an image of the repression Shideh struggles with, the society that will shape her young daughter.

Subtextually Shideh’s conflict with her society is reflected in the nature of the horror she faces. The djinn wants to take her daughter from her, to make her live in its world. Which implies what’s at stake not just metaphysically but ideologically. When we see the djinn near the end — a djinn Dorsa’s described as a woman — we get at first just a disquieting glimpse of someone in a chador. That image later expands, the cloth becoming a kind of labyrinth Shideh must negotiate. Dorsa’s life is at stake, her future; the djinn an image of the repression Shideh struggles with, the society that will shape her young daughter.

Similarly the djinn’s linked with war, apparently entering Shideh’s world by hitching a ride on the missile that crashes into her apartment building. The djinn helps bring abut the fragmentation of the small apartment building, driving wedges between neighbours. The phallic image of the missile driven into the building brings many themes together into one image.

At the same time, the symbolic aspect never interferes with the story itself. There’s a perfect union here of theme and story. Tension grows naturally due both to events inside the apartment building and also the growing danger of the war outside. Hints of supernatural weirdness grow harder and harder to deny. Slowly we come to half-understand the djinn, never given that much information but just enough to get a sense of what it wants and how it works; how the characters are already in deadly danger. Finally everything we know comes out in an exquisitely staged climax, where Shideh’s love for her daughter is tested (as the story form demands it must be) to its limits.

The movie creates a strong sense of Shideh’s apartment, of the sense not just of place but of a home. Bathed in warm yellows and oranges, it feels safe, a refuge from the colder colours outside. And yet we come to see this as something of an illusion. Danger can invade anywhere. Finally Shideh and Dorsa set out in an equivocal escape. But where will they go?

The movie creates a strong sense of Shideh’s apartment, of the sense not just of place but of a home. Bathed in warm yellows and oranges, it feels safe, a refuge from the colder colours outside. And yet we come to see this as something of an illusion. Danger can invade anywhere. Finally Shideh and Dorsa set out in an equivocal escape. But where will they go?

The movie’s told with a strong sense of craft, then, but it is anchored by a tremendous performance by Narges Rashidi as Shideh; her sense of strength and rebelliousness and frustrated gifts make her a memorable lead. She’s instantly an interesting character, a character who wants things but is frustrated in realising those wants. Strong-willed and assertive, she’s a powerful protagonist — and a surprisingly assertive lead for a horror movie, a woman always asserting her agency, ultimately consciously daring to pit herself against the monster in her life. Manshadi as Dorsa also deserves special mention, always believable, never too precocious or too annoying. The film lives on the chemistry between her and Rashidi, and they bring it to life.

Under the Shadow is a remarkable film. For me the most striking moment is the final confrontation where the world seems to expand, where the magic always just out of sight suddenly expands into something grander and even more terrifying. But that moment would be nothing without everything that comes before, the depiction of society and daily life and family, the slow build of horror, the shadow of war everywhere. Under the Shadow is intelligent, atmospheric, and always surprising. It’s a gem.

Under the Shadow is a remarkable film. For me the most striking moment is the final confrontation where the world seems to expand, where the magic always just out of sight suddenly expands into something grander and even more terrifying. But that moment would be nothing without everything that comes before, the depiction of society and daily life and family, the slow build of horror, the shadow of war everywhere. Under the Shadow is intelligent, atmospheric, and always surprising. It’s a gem.

Two movies that Thursday mixing horror and daily life, in two different ways; I responded much more strongly to the one that was more dramatic (and more tightly written). Two more monsters, one almost deconstructed to the point of mundanity, the other showing always more and more depth. Again I preferred the latter. Perhaps it’s simpler to say that, to me, one movie had interesting ideas but didn’t come off, while the other had interesting ideas that fed on each other in a more carefully-constructed structure. Either way, an interesting night of horror. In some ways, the two movies I’d see the next day would be an odd inversion.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.