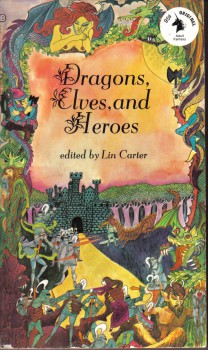

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: Dragons, Elves, and Heroes edited by Lin Carter

Dragons, Elves, and Heroes

Dragons, Elves, and Heroes

Edited by Lin Carter

Ballantine Books (277 pages, October 1969, $0.95)

Cover art by Sheryl Slavitt

It’s been a while since my last post, and no, I haven’t fallen off the face of the Earth, run away to join the circus, or been abducted by aliens. Although there have been times I’ve considered that circus thing. Or maybe gypsies.

No, I’m just overloaded this semester (my day job is in academia), which hasn’t left a lot of opportunity to read at a time when I’m not likely to fall asleep after a few pages.

And I wanted to take my time and do this one right. Dragons, Elves, and Heroes is the first of a two volume set in which Carter collects heroic fantasy imaginary world stories, beginning with a selection from Beowulf. This volume ends in the 1800s, although the most recent selection isn’t the last. The companion volume, The Young Magicians, will pick up where this one left off.

Anyway, this book looked like it would take some concentration, so I tried to read it when I would have time to devote to it. But enough about what happens to the well laid plans of mice and men.

I found the selections on the whole to be thoroughly enjoyable, with a few exceptions. I used the word “selections” intentionally, because other than a handful of poems, most of the stories Carter selected were excerpts. The one notable exception was the entire text of The Princess of Babylon by Voltaire was included. I wish Carter had stuck to his practice of using excerpts, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

The book opens with a selection from Beowulf (trns. By Norma Lorre Goodrich). I read Beowulf in senior English in high school. That was *cough* years ago, and I remember it fondly. I’d forgotten how much I enjoyed it, and I’ve bought a multi-translation ebook with the intention of reading and comparing multiple translations. Carter’s selection is from early in the poem, where Beowulf and his companions volunteer to spend the night in Heorot and face the monster Grendel.

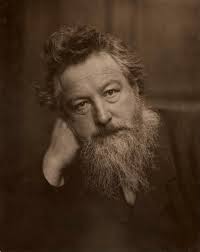

Next is “The High History of the Sword Gramm” from the William Morris translation of The Volsunga Saga, one of the great Norse sagas. I have a copy of this and came across it the other night when I was looking for something else. This selection tells the story of Sigurd (AKA Siegfried to modern audiences). Carter makes a point in his introduction to the story to show the influences of this saga on Tolkien. There are battles, the reforging of a broken sword, and the slaying of a dragon.

“Manawyddan Son of the Boundless” is from the Welsh Mabinogion, translated by Kenneth Morris (not William). It’s the story of the quest to find a king’s crown that turns into so much more.

William Morris (not Kenneth) was in large part responsible for popularizing the Norse sagas to the extent that more were translated into English. The Grettir Saga was one of the ones translated as a result of Morris’s work. In “Barrow Wight”, (trns. By S. Baring-Gould) the hero Grettir gets his magic sword by robbing a tomb of an ancient king. This one was one of my favorites.

Next we come to one of the more interesting selections, an excerpt from the poems of Ossian, “Fingold at the Siege of Carric-thura” . Ossian was an ancient Scot (3rd cent.), sort of a Gaelic Homer who composed 22 epic poems. Or so James Macpherson claimed. Macpherson also took credit for discovering the poems and translating them. This was sometime in the mid-to-late 1700s. (Carter doesn’t give an exact date, and I’m too lazy to look it up.)

There was just one problem with all this. Macpherson made every bit of it up. Not that the poems aren’t worth reading; just the opposite. I quite enjoyed the selection Carter chose, in which the hero Fingold is returning home and stops to visit a friend at Carric-thura, only to find the city under siege. Like any good hero, he does something about it. I’ve picked up an electronic copy of the poems of Ossian at Amazon.

Sir Thomas Mallory makes an appearance with “The Sword of Avalon” from Le Morte d’Arthur. I haven’t read Mallory, but I need to. I wasn’t familiar with this story, which concerns a sword that only the pure in heart can draw from a scabbard and the tragedy that comes from it. And no, Arthur isn’t the one who can draw the sword. Again, Amazon provided an inexpensive copy.

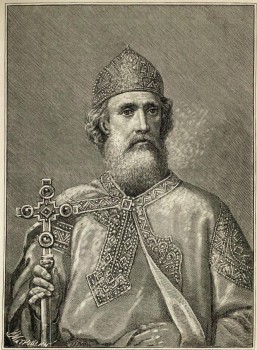

Next Carter moves into eastern Europe and The Kiev Cycle, which concerns Prince Vladimir of Kiev. He was the last of the pure Scandinavian prices of the city and a real historical figure. Vladimir is similar to King Arthur in that many of the stories deal with the adventures of his Bogatyrs, who were heroic warriors. “The Last Giant of the Elder Age” (trans. Isabel Florence Hapgood), though, is pure myth. It concerns the death of the last giant of the previous age.

The Kalevala is the national epic poem of Finland. It was compiled in 1849 In “The Lost Words of Power” (trans. John Martin Crawford), the hero Wainamoinen has been given a task to complete by the mother of his beloved, build a ship without using his hands. In order to complete his task he needs three words of power. This is the story of his quest to find them.

“Wonderful Things Beyond Cathay” from The Voyages and Travels of Sir John de Mandeville is an early travelogue consisting of a lot of tall tales. There’s no real story here, just descriptions of exotic places which may or may not be real written by a man who may or may not have existed.

The Gesta Romanorum (The Deeds of the Romans) is a collection of fables and tales that were compiled in the Middle Ages. The book is a collection of stories ranging from Classical times to what was contemporary at the time of compilation. Subject matter includes historical figures as well as kings and empires that never existed. Carter selected a group which he called “Tales of the Wisdom of the Ancients”. They’re shorts and often have a moral point, but I enjoyed them quite a bit.

Next is “The Magical Palace of Darkness” from the Medieval romance Palmerin of England. It was quite popular in its day and is referenced in Don Quixote (yes, that Don Quixote). Palmerin is a wandering English knight.

In the selection Carter included, he attempts to rescue an enchanted Greek princess. This one was a bit of a slog, as it consists of dense prose. Dialogue isn’t offset by new paragraphs or quotation marks. An English teacher would say that to call the sentences run-on would be an understatement. (One sentence opening a section of the story is over 19 lines long.) Still, there’s a cadence to the words that makes the reading enjoyable and not as much of a slog as you might expect from simply glancing at the text on the page.

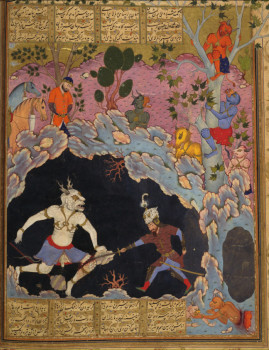

The Shah Namah (The Book of Kings) is the national epic of Persia. It was commissioned by one king to be the history of Persia from the Creation to his reign. The project wasn’t finished until 300 years later and even then took 35 years to write.

I have no idea how long it is; Carter doesn’t say. He does say that he didn’t care for any of the English translations available at the time, so he translated a portion himself. “Rustum Against the City of Demons” is the story of an aging hero who must rescue the foolish young prince who humiliated him after the princes is kidnapped and taken to a city of demons.

Carter translated the hero’s name as “Rustum”, but all other references I’ve seen have it as “Rustam”. The illustration to the right is the climax of the story and comes from a copy of the Shah Nama. Click image to enlarge.

Other than some poems, which I’ll mention in more detail next, the last selection is by far the longest. I’m not sure why Carter decided to include the entire text of Voltaire’s The Princess of Babylon.

The story opens with the king of Babylon having a contest to see who is worthy to marry his daughter. The kings of Egypt, India, and Scythia compete, but they aren’t able to complete the tasks set before them. A young man of common birth, Amazan by name, appears riding a unicorn and carrying a bird which turns out to be a phoenix. He’s able to complete all the tasks.

Of course he and the princess fall in love. He receives a message his father has died and goes home. All the kings are rejected, which launches three armies marching on Babylon. The princess manages to manipulate the situation in order to be sent on a pilgrimage during which she plans to visit her lover.

Only she’s captured by the king of Egypt. She pretends to love him in order to escape. A crow reports to Amazan that she has been unfaithful, and heartbroken, he set out to wander the world. When the princess reaches Amazan’s house and learns why he’s left, she pursues him.

And this is where the story went off the rails. What follows is the princess pursuing her lover throughout Europe and Asia and always missing him. Voltaire uses this technique to make social commentary on the different societies. The whole thing had a Cabellesque feel to it, in that the chronology and to a lesser extent geography didn’t always have an internal consistency. Before he started the social commentary, the fantasy was quite enjoyable, but that went out the window about a third of the way through.

There’s not a hard and fast line between the poetry and the stories since many of the selections in Dragons, Elves, and Heroes come from an older poetic tradition than most modern readers are familiar with. I went with what a modern reader would call poetry in making the distinction.

Poems included in the book are “Puck’s Song” (Rudyard Kipling), “Tom O’Bedlam’s Song” (Anonymous), “Prospero Evokes the Air Spirits” (William Shakespeare), “Childe Rolalnd to the Dark Tower Came” (Robert Browning), a selection from The Faerie Queen (Edmund Spenser), and “The Horns of Elfland” (Alfred Lord Tennyson). All of the poems fit the theme of the anthology.

Now, for the two of you who are still with me, to sum up. I found Dragons, Elves, and Heroes to be one of the most enjoyable titles in the BAF series that I’ve read so far. With the exception of Voltaire, I liked all of the stories to a greater or lesser degree. I think my favorites were the first few that drew on the Sagas. I’m not sure what that says about me, but those stories resonated with me more than any of the others.

Now, for the two of you who are still with me, to sum up. I found Dragons, Elves, and Heroes to be one of the most enjoyable titles in the BAF series that I’ve read so far. With the exception of Voltaire, I liked all of the stories to a greater or lesser degree. I think my favorites were the first few that drew on the Sagas. I’m not sure what that says about me, but those stories resonated with me more than any of the others.

I had expected the contents to be more work than they were. I was pleasantly surprised by how enjoyable the tales were. Maybe I’m developing (for lack of a better word) an ear for the rhythms of some of the older writers, or maybe it’s because so many of the selections had their roots in poetry, but I would be very open to reading more of this type of fantasy.

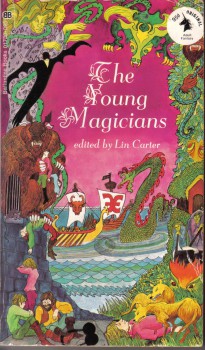

As I mentioned early on, Dragons, Elves, and Heroes has a companion volume. The Young Magicians picks up where the previous book leaves off and covers fantasy up to Carter’s time. I’ll not make any promises about how soon I’ll have the next post ready, since I’ve missed every writing goal I’ve set myself for the last three months. But I will get it done.

Join me, won’t you?

Recent posts in this series are:

Lin Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Lilith by George MacDonald

The Silver Stallion by James Branch Cabell

The Sorcerer’s Ship by Hannes Bok

Deryni Rising by Katherine Kurtz

Land of Unreason by Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp

The Doom that Came to Sarnath by H. P. Lovecraft

The Spawn of Cthulhu edited by Lin Carter

Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees

Figures of Earth by James Branch Cabell

Keith West blogs way more than any sane person should. His main blog is Adventures Fantastic, which focuses on fantasy and historic fiction.

With reference to the saga-hero, one may also check “Grettir at Thorhallstead” (apprxo. title) in Sam Moskowitz’s early 1970s anthology Horrors Unknown.

The whole saga is worth reading, though. It’s in Penguin Classics, but I like my University of Toronto paperback with good paper and even a few photographs, such as haunting images of Drang Isle, where Grettir made his last stand.

I recommend, for Malory, the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Le Morte Darthur: The Winchester Manuscript — except that one might skip the Tristram section, at least one’s first time through the Morte; I think readers are liable to bog down in them a bit, and arguably they are grafted on to the main narrative of Arthur, Merlin, the Round Table, Launcelot and Guinevere, the Grail quest, and the downfall of the House of Pendragon.

Browning’s “Childe Roland” is a weird masterpiece. I could wish that Carter had cut the Voltaire and substituted Coleridge’s “Christabel,” which even in its incomplete form is another weird masterpiece.

All of the BAF anthologies (and many of Carter’s non-BAF anthologies) were pretty top-notch — I think Carter’s greatest strength may have been as an anthologist. I might question some of his scholarship, but his awareness of the field at large (and especially the historical stuff) was second to none.

For your next project, read John Meyers Meyers “Silverlock,” track down all the works referenced therein, and read them. I think I managed to find and read about 90% of them, some of which overlap with the selections you mention above.

Major Wootton, I read Horrors Unknown back in high school, so I know I’ve read the story. I’m not exactly sure where the book is, so I’ll dig it out this weekend when I’ve got more time. And thanks for the recommendations on which editions to look for.

Joe H., I agree completely. I’m really looking forward to the rest of the anthologies.

Kan Lizzi, that’s a major undertaking. I read Silverlock when I was in college and loved it. But there were so many references. Maybe when I finish the BAF series…

Thanks for this! I have this and other Carter anthologies, picked up when I was a penniless student and such books were less than fashionable. Now I shall have to revisit the dusty boxes in the back of the cupboard.

I first read this anthology as a teenager in the early 70s. In the UK, the series was known as the Pan Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Pan being a popular UK publisher at the time. UK residents never got the full series – probably a mixture of copyright and lack of enthusiasm on the part of Pan. Lovecraft, Merritt, Cabell, Clark Ashton Smith were all sold in the UK, but under other paperback imprints such as Panther and Tandem. Anyway, in my UK edition, 7 stanzas of the Browning poem are missing. Carter’s intro does not state that he abridged the poem but there is an asterisk on the page which represents the missing stanzas. Is the full text in the US edition or is this a case of Carter taking liberties and not owning up to it? The missing stanzas are 12 through to 18.

I agree with Major Wooton that the Voltaire should have been dropped. He wrote better stuff than the Princess of Babylon, notably Candide which Carter dismisses as dreary but which is actually very funny. However, Candide is longer than the Princess of Babylon. Voltaire wrote plenty of shorter pieces, which would have been more appropriate. I also agree that Coleridge’s Christabel would have been a good choice, as would The Ancient Mariner and Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market.

The Shah Nameh is very long – probably over a 1000 pages. I have only ever seen abridged translations of it. Carter states that he is no Persian scholar. I suspect that his version is not based on the original but on other translations and is more a retelling than a translation per se.

Sorry, this all seems negative. This is one of my favourite anthologies, coming as it did, when I was fourteen. I was passionately fond of myth and legend and this book was the opening to the original narratives, rather than just retellings. It was here that I first encountered Norse Saga, Malory, Mandeville, the Mabinogion and the Kalevala as original text. Carter’s scholarship may have been woeful, but his knowledge of these literatures was vast.

Neil

Yep, that was always a hallmark of Carter’s scholarship — boundlessly enthusiastic and factually dubious.

And yes, I just checked my (US) copy and it seems to be missing the same stanzas of the Browning poem. (Ha! I _knew_ there was a reason I was hanging onto those Norton Anthologies of English Literature!)

Also agree with your conclusion re: the Shah Nameh — that he wasn’t translating so much as adapting.

“Goblin Market” — interesting that Carter didn’t reprint that one. It might be that his publisher said he must keep -poetry- to a minimum; that it puts off readers.

Otherwise, also what about Keats’s very eerie Faerie poem “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” or even Keats’s “Lamia”?

On the topic of fantasy poetry, “The Forsaken Merman” by Matthew Arnold would be a lovely choice.

Perhaps it is not as “heroic” as the rest of the pieces mentioned, as that seems to be a defining characteristic for the anthology selection. The same might be said of “Goblin Market”, which of course is wonderful, and I’d say heroic in its own way, but a sister’s love and self-sacrifice might not count as heroism in 1969.

M. Harold Page, you’re welcome. I’m enjoying doing these posts.

Neil, Joe H. is correct. Those stanzas are missing.I suspect the Shah Namah is something I would dip into from time to time rather than read straight through. After all, the author literally spent decades writing it. I’m not surprised it’s that long.

Several of you mention other poems, so I’ll address that here rather than individual replies. I loved the Ancient Mariner in high school, but I can see how it might not be considered heroic. Most of the other poems that have been mentioned I don’t recall reading, and some I’ve not heard of. I do enjoy poetry, so I’ll look them up and give them a try. Carter does say in his introduction, and repeats in other places, that he was looking for stories in a heroic vein and preferred imaginary world settings. I suspect that might be one of the reasons some poems that have been mentioned weren’t included.

So let me throw out this question: If you were making a reading list of fantasy poems, what fantasy poems would you include? You don’t have to limit yourself to heroic fantasy, either.

I can see that this is the Ballantine anthology that Lin Carter never got to edit – Adult Fantasy Poetry. He probably would have had a hard time persuading the publishers to go for it! Apart from the poems already listed, I would add Tennyson’s Lady of Shallot and, possibly, the Lotos Eaters; an extract from Milton’s Paradise Lost, actually not my cup of tea but relevant to the genre; The City of Dreadful Night by James Thomson – again, probably an extract as it is very long; perhaps an extract from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King; perhaps an extract from Spenser’s Faerie Queene – but it is a very strange work; an extract from Drayton’s Nymphidia along with Tolkien’s very telling review of it in his Fairy Stories lecture. If there was space, I would also include the whole of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, because it is so perfect. William Allingham’s The Fairies and too many poems to list by Yeats. Lastly, some poems by the likes of Lovecraft, Smith etc.

Neil

Oh and I forgot The Ingoldsby Legends by R H Barham. Popular in Victorian times but not read very much, these days, the legends are comic ballads and tales sending up Gothic novels, bloodthirsty penny dreadfuls and the like. They can be very funny. The most famous is The Jackdaw of Rheims, but that is one of the most anodyne. My favourite is the Lay of St Dunstan, which begins:

St Dunstan stood in his ivied tower

Alembic, crucible, all were there;

When in came Nick to play him a trick,

In guise of a damsel passing fair.

Every one knows How the story goes

He took up the tongs and caught hold of his nose.

Neil

Ha! I never knew that the Ingoldsby Legends were actually real — I just knew the name because one of the characters in King Solomon’s Mines (was it Quatermain himself) was a big fan, and recited the Legends during the famous eclipse scene.

What’s an even harder sell to publishers than poetry is drama, or so I understand. Carter did reprint one of Dunsany’s fantastic plays.

J. M. Barrie’s Mary Rose deserves to be better known to readers of fantasy, weird fiction, etc.

There’s also a play Johann Sigurjonsson, The Wish, based on an Icelandic legend of a pastor who practices black magic.

Here is something from the New York C. S. Lewis Society on Mary Rose:

Poe said that the death of a beautiful woman was the most poetical topic in the world. Not the death, but the disappearance, of a woman or girl is a choice idea for modern writers of fantasy.* Joan Lindsay’s fiction Picnic at Hanging Rock and the Twilight Zone teleplay “Little Girl Lost” by Richard Matheson are examples. Perhaps these are indebted to Mary Rose, a 1920 play that has been overshadowed by its author’s Peter Pan.

On vacation in the Hebrides with her parents, eleven-year-old Mary Rose disappeared from the small island where she was sketching. Twenty days later she was seen there again, and had no sense of the missing time. Her parents didn’t tell her about her disappearance or the efforts to find her, but, when a young man, Simon, courted her seven years later, they told him the story. A few years after that, the young married couple, parents of a little boy, came to “The Island That Likes To Be Visited,” and Mary Rose vanished again. Unmarked by time, she returned once more, after a hiatus of 25 years, during which period her husband, parents, and son suffered directly or indirectly because of their loss. The story’s present, however, is five years later, after Mary Rose, her husband, and her parents have died, when the son, who had run away to Australia, has come back to England and his mother’s home.

Lewis recalled Barrie’s play in a 1933 letter to Arthur Greeves. An “old haunting suspicion… raises its head in every temptation – that there is something else than God – some other country (Mary Rose… Mary Rose) into which He forbids us to trespass – some kind of delight wh[ich] …. would be real delight if only we were allowed to get it. [In fact, such a] thing just isn’t there.”

J. R. R. Tolkien saw a theatrical performance at some time, and read the play, first published in 1928. He comments on it in Note F to “On Fairy-Stories.” The 2008 expanded edition of the essay, edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas Anderson, contains a few additional lines on the play. It troubled Tolkien. Tolkien’s published note says that Barrie’s version of the common tale of humans who have spent years among the fairies is “painful… and can easily be made diabolic” if the performance changes the playwright’s conclusion by implying that the fairies –not Barrie’s angels – for the third time take Mary Rose or, rather, her ghost (thus depriving her of heaven). Tolkien’s manuscript addition says more about the “human torment” of the other characters thanks to the “malicious or inhuman” fairies’ abduction: Barrie’s own conclusion still offers no mercy for the victims. “[N]othing whatever is done with [their] horrible sufferings.” Is this, though, quite fair to the play as written? The Morlands confess to one another that their hearts were not broken, that is, their lives have not been utterly ruined, that happiness has broken through at times. Simon was able to serve his country well in the war, and though he apparently was a very difficult father to his motherless boy, yet the grown man who comes back from Australia is courageous and compassionate.

One should read Barrie’s play, if possible, in Peter Hollindale’s 1995 edition for Oxford’s World Classics, a volume that also includes Peter Pan and others.

In 2007, Mary Rose was revived at the Vineyard Theater in New York. The reviewer for the Times said that “this elegantly plotted ghost story [is] a more mature and mournful reworking of themes Barrie explored in the tale of the boy who refused to grow up.”

PS That Mary Rose article is copyright by the New York C. S. lewis Society, but reprinted here with the OK of the author (me).

Other poems that could be included in an anthology of fantasy poetry:

+ The Pied Piper of Hamelin (to go with Childe Roland)

+ The Raven by Edgar Allen Poe (duh)

+ The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll

+ Bishop Hatto by Robert Southey (more horror than fantasy but those rats seem to come from a speculative universe)

+ The Rape of the Lock (gnomes, sylphs, salamanders and faeries in a Terry Pratchett-style comic universe)

For fantasy poetry, how about “Darkness” by Byron. Also parts of Sigurd the Volsung by William Morris would fit in well.

Wow, ask a simple question and get some fantastic responses. I’ll have to do that again.

These are some great suggestions. I’ve not heard of many of them. I’m definitely going to have to get my hands on a copy of MARY ROSE. It sounds a little like Robert Nathan’s PORTRAIT OF JENNIE in reverse.

And there would have to be some of Robert E. Howard’s poetry.

I suspect Carter would have put together an anthology of drama if he could have sold the idea to the Ballantines.

NeilH, in the quote you provided (thanks, btw), is “nose” used in a literal sense or a James Branch Cabell sense?

Major Wootton, thank you for the quote.

Some of the later poems by Hilda Doolittle might work. Vale Ave probably comes closest to the mood of the existing anthology.

Nose is literal. The original legend is that St Dunstan was working in his forge, fashioning church bells or vessels, when the devil appeared in the guise of a woman. Dunstan pinched the devil on the nose with his tongs, to make him go away. But the author states he is going to ignore this legend and tell another, which is a variant on the Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Dunstan commands his broomstick to do certain tasks and is overheard by his apprentice Peter. When Dunstan is away, Peter commands the broomstick to bring him ale. Not knowing the command to stop the broomstick, ale is brought along with more ale, etc. etc. Peter breaks the broomstick in half, with the result that two broomsticks keep bringing ale. Unlike the Goethe ballad or the Mickey Mouse film in Fantasia, Peter comes to a bad end:

While Peter who, spite of himself now had drunk hard,

After floating awhile like a toast in a tankard,

To the bottom had sunk, And was spied by a monk,

Stone-dead, like poor Clarence, half drown’d and half drunk.

Neil

Sarah, I’ve not heard of Hilda Doolittle, but I’ll make sure to look her up.

NeilH, I was only joking, but thanks for the clarification and the quote.