Things Your Writing Teacher Never Told You: It Was Only A Dream…

Just as there are certain guitar licks, walkdowns, turnarounds, and other patterns that can help with the flow and structure of a song, writing and storytelling have some generic techniques that can be used to great effect, or great failure, depending on how, when, and why they’re applied.

Just as there are certain guitar licks, walkdowns, turnarounds, and other patterns that can help with the flow and structure of a song, writing and storytelling have some generic techniques that can be used to great effect, or great failure, depending on how, when, and why they’re applied.

The most universal and familiar in fiction is probably the framing device that starts many children’s stories: “Once upon a time…” and ends them with, “And they lived happily ever after.” Those phrases are an emotional touchstone for most readers, taking them back to a magical time when stories were a centerpiece to our lives.

But most of these shortcut techniques aren’t used as often, and aren’t guaranteed to evoke a specific emotional response. Let’s look at a risky writing technique: The “It Was Only A Dream…” ending.

I generally hate this kind of ending, because it feels like a trick. It feels like the writer is chanting “Neener neener!” and laughing at the audience who fell for this prank.

However, as Eric Cherry (my frequent writing-neepery partner) and I explored specific instances of it being used, I realized that I didn’t always hate it. I just have such a strong emotional reaction when it’s used badly that it overshadows my appreciation of the times when it’s used well.

To use it in a way that respects the audience, it should shine the light of what we know about the story through a prism that reveals new facets to the story, rather than negating all that came before. It should make us embrace what we’ve already experienced within the story, and then view all of that in a new way.

Though you find this technique used across a spectrum of media, let’s take three well-known examples from television, all of which happened in the Eighties. (Well, one was in 1990, but close enough.)

Dallas, Don’t You Dare!

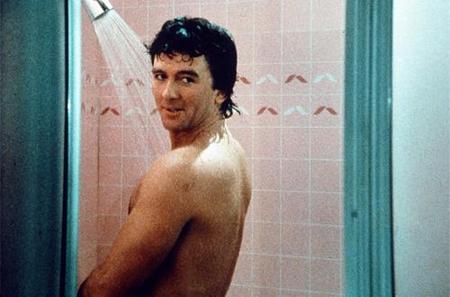

The first instance that leaps to mind, at least to people who are over the age of 40 or who watch re-runs of 1980’s prime time soap operas, is the 1985-86 “Dream Season” of Dallas. The entire 9th season of this cheesy melodrama — in which Bobby Ewing, a popular character, was killed off — was annulled by the first episode of the 10th season, where Bobby is shown in the shower, thus revealing that the entire previous season had all been his wife’s bad dream.

Cue the obnoxious “Haw-haw!” laugh by The Simpsons’ biggest bully, Nelson Muntz.

The writers may have killed the Bobby Ewing character off because the actor, Patrick Duffy, wanted to leave the show. And maybe it made sense — since both Dallas’s ratings and Duffy’s career seriously declined after he left — to bring the character back.

But soap operas, like the fantasy and horror genres, are very good about bringing dead (or mostly-dead) characters back to life. (Hey, Buffy died twice.) So there were plenty of other revival techniques that could have been used that weren’t so disrespectful to both the audience and the other characters of Season 9. But the writers basically painted themselves into a corner and then panicked and ran across the wet floor, rather than brainstorming creative ways to escape.

The only good thing to come from the Dallas Dream Season is it sparked an idea for an elaborate ending to the Newhart situation comedy in 1990.

Oh, Bob!

A little background for those who don’t spend hours watching nick@nite. The comedian Bob Newhart starred in two legendary television comedies. In the Seventies, he played psychologist Bob Hartley in The Bob Newhart Show. (This is back in the days when TV comedies often used their star’s name for the title of the show, even when the character had a slightly different name. See as another example The Mary Tyler Moore Show, whose show character is named Mary Richards.) Bob’s character was married to Emily, played by Suzanne Pleshette. It was a good show, and it was big hit for many years. But all good things come to an end, and the show was wrapped up in 1978.

A little background for those who don’t spend hours watching nick@nite. The comedian Bob Newhart starred in two legendary television comedies. In the Seventies, he played psychologist Bob Hartley in The Bob Newhart Show. (This is back in the days when TV comedies often used their star’s name for the title of the show, even when the character had a slightly different name. See as another example The Mary Tyler Moore Show, whose show character is named Mary Richards.) Bob’s character was married to Emily, played by Suzanne Pleshette. It was a good show, and it was big hit for many years. But all good things come to an end, and the show was wrapped up in 1978.

In the last episode of the 1977 season, both Bob’s wife and his receptionist are pregnant. But in the beginning of the next and last season, Bob reveals that both pregnancies were all a bad dream. (Maybe this is where the Dallas writers got their idea.) This isn’t the cool moment — that’s still coming.

In 1982, Bob Newhart returned to the national sitcom lineup with a show called Newhart, in which he plays a Vermont innkeeper named Dick Loudon. His wife was Joanna, played by Mary Frann. They’re surrounded by a cast of quirky characters. Like his previous sitcom, this show was an immediate hit and won numerous awards. But again, all things must end. This show wrapped up in 1990. But it did so with a final episode that goes down in the annals of TV as one of the best endings of all time. That’s not hyperbole. TV Guide magazine chose it as the best finale in television history.

Throughout the final episode, weird things happen. It starts with a Japanese tycoon buying out the entire resort town, with only Dick and Joanna holding out, while everyone else takes the money and runs. It quickly moves to five years later, when their inn is now situated in the middle of a golf course. All their old friends and employees come back to visit and create ever-escalating bizarreness and chaos. Silent characters speak for the first time, and the normally unflappable Dick finally storms out, shouting, “You’re all crazy!” and is promptly knocked out by a golf ball.

In the final scene, we see Bob Newhart in bed with his wife… from the previous show. Dr. Bob Hartley explains his weird dream to Suzanne Pleshette, and it is revealed that his entire second sitcom was just a crazy dream his character from his previous sitcom had had.

It is a brilliant send-up of Dallas, and it pokes fun at many of the tropes and characters of both Newhart’s shows.

Let’s look at one more detail the writers included: they wove parts of the theme song and credits of the previous show throughout the final episode, thus doing some subtle foreshadowing of the ending. It was the perfect wrap-up of both the Newhart series, and it was a brilliant use of the “It Was Only A Dream…” trope.

A Gentle Snowfall

“It Was Only A Dream…” fits most easily into ludicrous, comedic stories. It is, in effect, a punch line. But with effort, it can be made to work effectively with more dramatic stories, as well. The final example I want to explore here is St. Elsewhere. This medical drama was also a black comedy, though it was billed as “Hill Street Blues in a hospital.” It featured an ensemble cast and serialized storylines. So, it could be argued, it fell smack in the middle of Dallas and Newhart in style and tone. It was not a big hit, but it had a cult following among the key young demographics, and it earned a lot of Emmy Awards . It ran for seven seasons, from 1982-1988. And yes, that really was Denzel Washington in the cast.

“It Was Only A Dream…” fits most easily into ludicrous, comedic stories. It is, in effect, a punch line. But with effort, it can be made to work effectively with more dramatic stories, as well. The final example I want to explore here is St. Elsewhere. This medical drama was also a black comedy, though it was billed as “Hill Street Blues in a hospital.” It featured an ensemble cast and serialized storylines. So, it could be argued, it fell smack in the middle of Dallas and Newhart in style and tone. It was not a big hit, but it had a cult following among the key young demographics, and it earned a lot of Emmy Awards . It ran for seven seasons, from 1982-1988. And yes, that really was Denzel Washington in the cast.

In the final episode, the hospital is scheduled to be shut down, but is still, for a little while, treating patients. An older doctor tells Howie Mandel to go home, he’s finished his residency. There’s no more for him to do. Howie says, “No sir. It ain’t over till the fat lady sings.” And right on cue we hear an operatic soprano start up. A curtain in one of the ER bays is pulled open, and we see a hefty woman in full Wagnerian Valkyrie getup singing. The scene fades into an even older doctor’s office where he’s listening to a mellow, rather sad, opera song as he packs his things. Outside the window of the hospital, it is snowing, blanketing the grounds.

The final scene shows a grandpa watching over an autistic teen. The boy’s father comes in. (Both men were doctors in the series.) Through dialogue, we learn the man is a construction worker. The house that the three generations of men live in is small and shabby. The boy is sitting on the floor shaking a soccer-ball sized snow globe. The men talk about how that’s all he does, and how they don’t really understand this autism thing he has. The boy is coaxed into putting the snow globe in its stand, and all three leave the room to get ready for dinner.

The camera zooms in, and as the snow continues to swirl in the globe, the hospital is revealed. The whole series has been the fevered imaginings of an autistic boy who can’t communicate all the complicated, complex things going on in his mind to his dad, his granddad, or the world.

The camera zooms in, and as the snow continues to swirl in the globe, the hospital is revealed. The whole series has been the fevered imaginings of an autistic boy who can’t communicate all the complicated, complex things going on in his mind to his dad, his granddad, or the world.

The show’s constant blend of drama and humor, with transitions that moved the show seamlessly between the two tones, is what made the “It Was Only A Dream — Snow Globe” ending perfect.

Before We Roll the Final Credits

I guess the real problem with this sort of ending is that, after two wildly-popular shows do it so very successfully, and one does it so spectacularly horribly in front of all America, it’s hard to imagine how you could make the technique feel fresh and vibrant. Those series pretty much own that technique. Should writers stay away from it now, for fear of (at best) being called derivative, or (at worst) being compared to the Dallas failure?

Quite probably. At least that’s the advice I’d give most writers.

Of course, people are always saying there’s nothing new that can be done with vampires, and then Nancy A. Collins, and then Anne Rice, and then Stephenie Meyer, and then Charlaine Harris comes along. You may not like what they all did with vampires, but they did reinvent and re-energize one of the oldest tropes in the field. In the right hands, old things can become new again.

So, how do you feel about the “It Was Only A Dream…” trope? Have you read that ending in any genre short stories or novels? Did it work, or didn’t it? Why? I’d like to hear from you.

Tina L. Jens has been teaching varying combinations of Exploring Fantasy Genre Writing, Fantasy Writing Workshop, and Advanced Fantasy Writing Workshop at Columbia College-Chicago since 2007. The first of her 75 or so published fantasy and horror short stories was released in 1994. She has had dozens of newspaper articles published, a few poems, a comic, and had a short comedic play produced in Alabama and another chosen for a table reading by Dandelion Theatre in Chicago. Her novel, The Blues Ain’t Nothin’: Tales of the Lonesome Blues Pub, won Best Novel from the National Federation of Press Women, and was a final nominee for Best First Novel for the Bram Stoker and International Horror Guild awards.

She was the senior producer of a weekly fiction reading series, Twilight Tales, for 15 years, and was the editor/publisher of the Twilight Tales small press, overseeing 26 anthologies and collections. She co-chaired a World Fantasy Convention, a World Horror Convention, and served for two years as the Chairman of the Board for the Horror Writers Assoc. Along with teaching, writing, and blogging, she also supervises a revolving crew of interns who help her run the monthly, multi-genre, reading series Gumbo Fiction Salon in Chicago. You can find more of her musings on writing, social justice, politics, and feminism on Facebook @ Tina Jens. Be sure to drop her a PM and tell her you saw her Black Gate blog.

I don’t think making a parody of a bad thing counts as an example that it can be done well. If we laugh because of it, it’s because we’re laughing at those people who thought it would be a good idea.

“It was a dream” can be interesting. But “It was ALL JUST a dream” does not. I think it can never be anything but bad.

It’s lying to the audience and then laughing at them for being too dumb to notice something they could not possibly have noticed.

I think it’s quite possibly the worst cliches in fiction ever.