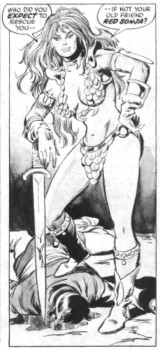

In Defense of Red Sonja: The Chain Mail Bikini

After only two appearances in Conan the Barbarian (issues 23 and 24), Red Sonja was already on her way to becoming a fan favorite. A strong, intelligent woman with the courage of Conan, if not his strict moral code (or upper body strength). Her dress sense (a chain mail tunic and red shorts) provided ease of movement and showed just enough skin to be sexy without being exploitive.

After only two appearances in Conan the Barbarian (issues 23 and 24), Red Sonja was already on her way to becoming a fan favorite. A strong, intelligent woman with the courage of Conan, if not his strict moral code (or upper body strength). Her dress sense (a chain mail tunic and red shorts) provided ease of movement and showed just enough skin to be sexy without being exploitive.

So where did the chain mail bikini come from?

Before the Internet, fan art was published mostly in fanzines or pin-up pages in comics. Artist Esteban Maroto was the first to draw Red Sonja in her now-famous bikini and, having nowhere else to publish it, mailed it to Conan writer/editor Roy Thomas. The visual was so striking that, when she next made an appearance, artist John Buscema drew her in the same outfit. Furthermore, Maroto was hired to draw the back-up story in that same issue. And to make it a hat-trick, a third artist (none other than Boris Vallejo) painted the cover art with the metallic swimwear.

The issue where all this took place would have been iconic anyway. Savage Sword of Conan 1 premiered in August 1974. The popularity of Conan the Barbarian had made the publication of a second Conan book just good business sense. To give you an idea of just how popular the character was, Marvel wouldn’t get around to publishing two Spider-Man titles until 1976.

Of course, Savage Sword would promise to be far from more-of-the-same. Its format as an over-sized black-and-white publication classified it as a magazine rather than a comic book. “So what?” you may ask. In 1974, comics were still heavily regulated by the Comics Code Authority. There was only so much violence (and sex) that could be shown in Conan the Barbarian. But as a ‘magazine’, Savage Sword of Conan could show as much violence (and, eventually, nudity) as Marvel dared. And as the series went on, they dared a lot.

Right now, as I type this and most likely as you read it, a movie titled John Carter of Mars, based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel A Princess of Mars, is in production. Not in development. Not in pre-production. Not in meetings. It is in front of cameras. Andrew Stanton, director of the brilliant CGI Pixar films Finding Nemo and WALL·E, is shooting John Carter of Mars from a script by Stanton, Michael Chabon, and Mark Andrews, in London this very minute, in this dimension, and it will reach theaters in 2012, in time for the novel’s one hundreth birthday.

Right now, as I type this and most likely as you read it, a movie titled John Carter of Mars, based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel A Princess of Mars, is in production. Not in development. Not in pre-production. Not in meetings. It is in front of cameras. Andrew Stanton, director of the brilliant CGI Pixar films Finding Nemo and WALL·E, is shooting John Carter of Mars from a script by Stanton, Michael Chabon, and Mark Andrews, in London this very minute, in this dimension, and it will reach theaters in 2012, in time for the novel’s one hundreth birthday.