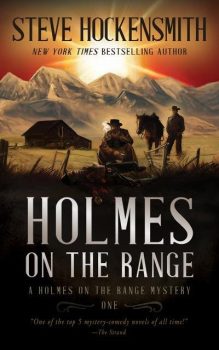

Holmes on the Range: A Chronology (October 2025)

There are a lot of ways to go about writing a Sherlock Holmes story. Some folks attempt to very carefully emulate Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s own style, and to turn out a tale that feels as if it might have been penned (or typed these days) by the creator of the great detective himself. No surprise that results vary. GREATLY. Hugh Ashton and Denis O. Smith are the best I’ve found in this regard. Last week, I took a deep dive into Steve Hockensmith’s Holmes on the Range series. You might want to click over and read that. Below, I present a complete chronology of the series (along with a list in publication order, following). Each entry comes with a non-spoiler summary – the kind of thing you’d find on a dust jacket or on a back cover. I think this is a useful reference to a terrific series. Steve himself reviewed and assisted, so it’s accurate. Come back next week for a Q&A with Steve, to wrap up our series.

There are a lot of ways to go about writing a Sherlock Holmes story. Some folks attempt to very carefully emulate Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s own style, and to turn out a tale that feels as if it might have been penned (or typed these days) by the creator of the great detective himself. No surprise that results vary. GREATLY. Hugh Ashton and Denis O. Smith are the best I’ve found in this regard. Last week, I took a deep dive into Steve Hockensmith’s Holmes on the Range series. You might want to click over and read that. Below, I present a complete chronology of the series (along with a list in publication order, following). Each entry comes with a non-spoiler summary – the kind of thing you’d find on a dust jacket or on a back cover. I think this is a useful reference to a terrific series. Steve himself reviewed and assisted, so it’s accurate. Come back next week for a Q&A with Steve, to wrap up our series.

A HOLMES ON THE RANGE CHRONOLOGY

ss – short story; nvlla – novella; nov – novel

(ss) Shadow of the Badger (1871)

Te next story kicked off the Holmes on the Range series. But Steve wrote a prequel involving Gustav, when he was just six years old. His mother is in bad shape after having her fifth child who I believe is Otto). The eldest – eight year old Conrad, – has a ‘plan’ to save their mother, and Gustave joins him in the effort.

(ss) The Truest Story Ever Told (1879)

Oswin Diehl, operative of the Double-A Western Detective Agency, had been a solider in the U.S. Army. This is a flashback to his time in charge of some cavalry Buffalo soldiers, assigned to hunt down an Apache chief, causing trouble with his band of renegades. When a not-friend from his West Point days shows up with some green soldiers, plus a newspaper reporter who doesn’t let facts – or even reality – get in his way, problems ensue. Includes an appearance by another future Double-A Western op.

(ss) Dear Mr. Holmes (July 1892)

So begins the Holmes on the Range saga. Gustav (Old Red) and Otto (Big Red) Amlingmeyer travel to Brownsville, TX, to sign on for a cattle drive. They’re gonna help move three thousand Mexican longhorns all the way up to Billings, Montana. En route one night, there’s a stampede. As they get the herd back in place, two of the cowboys are found, stomachs slashed, eyes cut out, and scalped. Clearly, Indians had raided the drive and killed the men. Except, Gustav’s not quite so sure. For the first time, he gets to try out the Holmes methods he’d heard sitting around the campfire and listening to Otto read “The Red-Headed League.” A stranger shortly joins the group, a lawman shows up, fireworks ensue, and Big Red gets the detection’ bug.