The Complicated Morality of Joel Miller

Hello! I’m back with more The Last of Us stuff because I’m not quite done with it all. I want to talk about how the first game (and the first season) ended, and the maelstrom of morality debates that followed the incredible, tortured conclusion.

What follows will include spoilers, so if you haven’t played the game or watched the series, you might want to go ahead and do that and then come back to this.

For those of you who need a recap, Joel and his charge, Ellie, make it to the Fireflies after crossing the entire (former) United States of America. They made this journey because Ellie is immune to the mutated cordyceps fungus that is making horrific zombies out of nearly everyone. The Fireflies are hoping to make a vaccine against the fungus; thereby restoring society that was utterly obliterated when humanity lost its collective mind.

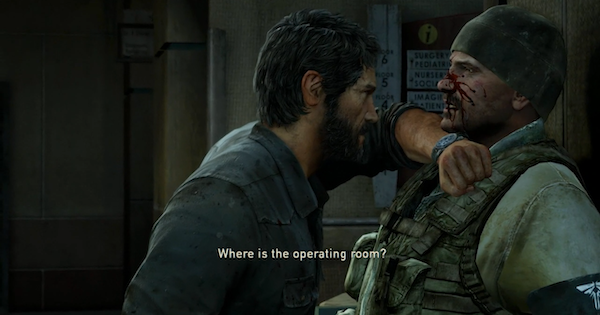

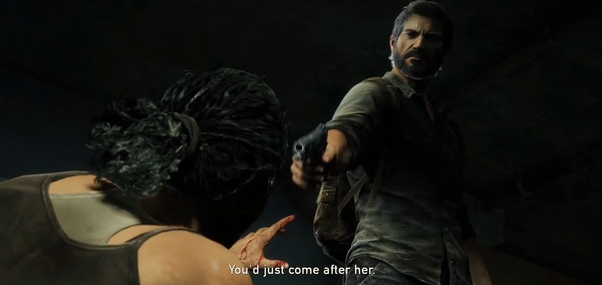

In the beginning Ellie, and therefore the audience, is convinced that the secret lies in her blood. When she and Joel arrive, however, it is revealed that actually, they must cut into her brain — killing Ellie. Joel, who was first very reluctant to have anything to do with this sassy child but grew ever more attached as they journeyed together, decides that this is unacceptable. He rescues Ellie. That rescue results in the utter obliteration of just about every Firefly in the facility.

When the game came out, there were arguments across forums about whether what Joel did was the right thing. Joel, in this game (and its adaptation) is a true anti-hero. Heroes, when it boils down to it, are selfless creatures. They would sacrifice themselves or their happiness in order to save the world. But when presented with that option, Joel casts it aside. Rightly or wrongly, he rejects the conception of hero at its most basic iteration.

He acts selfishly. He saves the life of someone he loves, and damns all of humanity in doing so. In fact, his character arc was never “hurt and selfish violent man grows into selfless, softer hero.” It was always “hurt and selfish violent man heals his many emotional wounds.” He remains, ultimately, selfish and violent.

I love Naughty Dog for making this so. It makes for a far more compelling protagonist; one whom I feel particularly protective of, even though I know he’s not, by most measures, “good.”

It’s a wonderfully morally grey area, and it’s been fascinating to observe. While I know precisely where I stand on the issue, I understand both sides of the aisle. Is it ethical to murder a child in the hopes of saving humanity, or does our morality demand we save the child and damn humanity? Is murder justifiable in this case? For either side? It truly boils down to a singular question:

Is one life worth thousands? Millions?

But there’s a lot of nuance and suppositions in the arguments for and against that make this more contentious than one might think initially.

On one hand, the doctor who has worked with the Fireflies in order to get this chance at a vaccine is thinking large-scale. All of humanity could be spared from this terrible infection. If a vaccine is created, all the fear, and the abuses of power created by that fear (hello, Fedra) would be hopefully resolved. Humanity could return to pre-infection society, and all the evils that occurred in the quest for survival could be put behind them. On an individual level, families wouldn’t be torn apart (sometimes literally) by infection. Runners would no longer be created, sobbing as they tear their own loved ones apart to feed. So many lives could be saved and improved.

I know a good many people who fall into this camp. They give many reasons, like those listed above, but also remark on Ellie’s character. Ellie would have unquestionably consented to her own death in the hopes of saving humanity, is the argument.

To be fair to them for this assumption, I’m actually quite certain that they are correct in this supposition. I have absolutely no doubt that Ellie would consent.

But, and this is a massive “but,” they never ask for that consent. They do not give Ellie any choice in the matter. They simply put her under, and prepare for murder. Were they right to do so? Was Joel right to stop them?

On the other side, we have people arguing that murder is murder, and murdering a child, no matter the reason, is evil. Under no circumstances do the ends justify these means.

This goes beyond simply understanding Joel’s motives. He’s lost so much already; including his daughter at the very start of the fungal apocalypse. Ellie filled that enormous hole. Of course he would fight to protect her (and, ultimately, himself. There was no way he’d willingly go through that kind of pain again).

There are many arguments for this side of the divide. For starters, there was no real guarantee that a vaccine could be procured at all (though those that were in the know did confirm that it would have worked). There were too many “maybe”s and “if”s to make killing Ellie a worthwhile choice; particularly since she was the only immune person that they knew of. Was killing her in an attempt to find a vaccine without an absolute guarantee the moral thing to do? Would it be immoral not to try, if trying might offer a chance to save humanity?

And while it’s true Ellie likely would have consented to death to save humanity, there are complications with that consent. She’s fourteen year old girl, struggling with survivor’s guilt AND had just been through a terribly traumatic incident (thanks, David, you absolute [redacted]) that would have had a profound effect on her psyche. Even if they had acquired her consent, given her emotional state, would it have been a reasoned decision?

There are other arguments which range all over the map.

There’s the question of humanity itself. There is a wildly misanthropic argument to be made against trying to save humanity at all. Prior to the apocalypse, humanity was a blight – mass deforestation, poisoned water-systems, emptied water tables, runaway global warming… To hit a little close to home at present, it really seems like the best way to save the world is to well, do away with us altogether. So… cordyceps damned humanity, but saved the world. Is saving humanity actually ethical at this point? Is returning to pre-pandemic life with all its late-stage capitalist cataclysms something they really ought to be striving towards?

We do tend to centre humanity in all of our considerations for obvious reasons. It has to be said though, when people talk of ‘saving the world’ they’re actually talking of ‘saving humanity’ and those two things are not really the same, are they? Not currently, in any case (when taking humanity as a whole – certainly arguments can be made for certain individuals or groups… but then that opens up an whole other bag of moralistic problems).

Humanity in the narrative didn’t exactly make a stellar recommendation for itself, between fascist military juntas, mass-murdering ‘freedom fighters’ and bandits, and let’s not mention paedophilic cannibals.

Further, it’s not like humanity couldn’t adapt to their new reality. We are the cockroaches of the mammalian world, after all. We’ve conquered almost every single biome. In this narrative, humanity did endure, creating a society that wasn’t predicated on being the very worse version of itself. Tommy and his wife, Maria, showed us that such a life was possible. Yes, under this reality, cordyceps would always be a problem, but with careful management and cooperation (which I would argue is the only way humanity will survive anything we will face), a good life is possible. Would it be harder than life without the fungus? Yes. Duh. Would we be without many of the luxuries humanity has become accustomed to (and have destroyed the world for)? Yes. Is that a bad thing? Depends on your perspective, I guess.

Humanity wasn’t exactly starting from absolute zero. It may well be that a cure or vaccine could be discovered later, without having to resort to the murder of a child.

I think it’s pretty clear where on the divide I fall, even if you haven’t read my previous articles on the game and it’s HBO adaptation. I don’t think the Fireflies were right. I don’t think killing Ellie was the right or moral thing to do, even if it resulted in a viable vaccine. I am 100% on Joel’s side. But I also know that it’s complicated, and I am in no way claiming moral superiority here.

The complication is why I find this story so compelling, and I am relishing bouncing between forums and debates, reading everyone’s perspective. There are so many great arguments to be had on either side.

My interest in the conundrum remains strong. Where on the divide do you fall? Kill Ellie and hope to save humanity, or save Ellie and hope humanity can find its way? Let me know in the comments below.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favourite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, occasionally teaching at the University of Ottawa, and cuddling her cat. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, teaching about historical death, and cuddling a furry murderer. Her latest novels are Skylark, Daughters of Britain, and Human.

Joel’s Dilemma is a weirdly, wonderfully inverted version of the (in)famous Trolley Problem. In the original, the Agent can watch a runaway trolley car run over 5 people or throw a switch to divert it to another track and kill 1 person. The situation presumes some perfect knowledge, so for Joel, we need to add in the information that, yes, the experiment on Ellie will produce a vaccine (saving the 5 people, at the cost of killing 1). But, for Joel, the active move is saving Ellie, so effectively, he is throwing the switch to send the trolley down the crowded track (kill 5, save 1).

And also we color everything with personal knowledge, as Joel knows/loves that 1 person. Which takes up another ethical conundrum: “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” That is probably Joel’s line of reasoning in a nutshell. As well as noting that this particular trolley is far from “runaway”; it is being actively piloted down that Ellie-occupied track. So Joel would not be letting Nature takes its course with Ellie’s death but would be participating (even if only passively) in her death.

The Trolley Problem is generally a thought experiment to examine the Principle of Double Effect: doing an action to cause both a “small” bad and a “big” good result, so that the net outcome is positive (+4 lives saved). There is no clear answer, though, and lots of issues about how “small” that bad result needs to be compared to the “big” good, or how morally “clean” the action itself has to be (e.g., is it OK to shoot an operator to stop the piloted trolley?).

With all the parties in Joel’s Dilemma looking ethically compromised (wanna tell Ellie what the plan is, first, Fireflies?), I tend to side with Joel. The other great fictional treatment of this issue is Ursula Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”, and her heroes do exactly that: walk away from an ethically flawed situation (which I interpret as a metaphor for Buddhism’s refusal of our material existence’s illusions). For Joel, the stakes are higher; he is not leaving Ellie in a miserable condition but allowing her to be condemned to death. Lock and load, Joel. Lock and load.

To be honest, I’m not sure Joel had much reasoning beyond his personal motivations. I don’t think he considered the lives that could be saved at all. He wasn’t not there. I don’t think he would ever get there. He’s too selfish, in my opinion, to even consider it.

Losing Ellie would hurt too much, so he’s not going to lose Ellie. I honestly think it’s that basic for his character (as I’ve interpreted it, in any case).

And I love that about him.

The problem with the Trolley Problem is that it continues to be “The Trolley Problem” – and the reason for that is that someone used a toy railway to demonstrate that *IF* the switch that diverts the rail is at all functional, it’s actually possible to save everyone.

So now some new allegorical framing device is needed to present the dilemma of passively allowing or actively preventing a tragedy at the expense of having actively committed a harm.

Back to the matter at hand, I agree – the situation in The Last of Us is ethically compromised – nobody gives Ellie the opportunity to choose to sacrifice herself willingly, there’s no explicit guarantee of a cure (in fact, one examination of the underlying situation surmises that her brain would *not* contain a cure, that Ellie is infected by a benign competitor strain of Cordyceps and as such, her living to pass on this more symbiotic Cordyceps to others is the actual cure!) Joel made the best decision based on an incomplete picture of what was going on. Heck, the fact that the Fireflies didn’t tell Ellie the truth I take as an indicator that they could very well be lying to Joel too.

Yeah, I’m fully on Joel’s side here.

One way to update the Trolley Problem is to turn it into the Autonomous Vehicle Problem: A self-driving vehicle can deliver its passenger to their destination safely but will endanger/kill 5 pedestrians, or it can divert to spare the pedestrians but crash and kill its passenger. I suspect most of us would, at least initially, imbue the Autonomous vehicle with some obligation to its passenger’s safety, which would make this version correspond a bit more to Joel’s ethical issue over saving Ellie and killing a lot of Fireflies.

And, interestingly, we get a fail from our usual science-fiction AI ethical standard, Asimov’s 3 Laws of Robotics, since the First Law (“A robot may not injure a human, nor through inaction, allow a human to come to harm”) prevents the Autonomous Vehicle from doing anything other than shutting down.

I’ve never played The Last of Us (or seen the series) so this is pure speculation – but I’m guessing Joel’s decision was simply a ploy by the original game designers to create an additional level? Joel delivers Ellie to the Fireflies, only to then discover what they intend to do to her. So of course he has to shoot his way out – ie, the designers were more preoccupied with milking the storyline than moral nuance.

Maybe. I don’t think that’s right, though. While the moral conundrum itself might not have been the focus of the scene in game or in adaptation, I do think that Joel’s character, and the impossible situation he found himself in, absolutely was. It was in service to the story, rather than ‘milking’ it. I really do feel like Neil Druckman and the team at Naughty Dog had a story to tell. Rather than a book or a show (initially, at least) they used the medium of a video game to tell it; and did so brilliantly.

The Last of Us was a brilliant story, brilliantly told that also happened to combine great, fun, and often terrifying game play.

Video games have been at the top of some of the best story-telling of late, what with The Last of Us, Ghost of Tsushima, both recent God of War games (the 2018 title and Ragnarok), and Hellblade – just to name a few that I’ve played. They’ve managed to tell their stories incredibly well; better than some books I’ve read and most shows I’ve watched.

That does seem credible, particularly as there’s a lot more effort put into the world-building and character development these days. I guess people’s expectations are higher? Interesting to see how it’s evolved, though – ie, into an examination of how to tell a good story.

I know that in the case of God of War, I was utterly blown away by the 2018 release. The previous games were fun, but the story wasn’t great and was really just a device to get the player to obliterate as many pixelated beasts as possible. Fun, but not really affecting.

My heart damn near exploded at the end of the 2018 release.

Not all video games, obviously. The PvP and fighting games generally have story-ish, but the focus is rightly on the game play. That said, so many of the modern games are producing exceptional stories (let me tell you how I sobbed, SOBBED at the end of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice).

Even a quick google reveals an interesting shift in term of motive – ie, from revenge to something more positive: honouring a dead partner, rescuing a loved one etc.