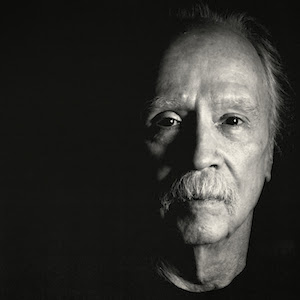

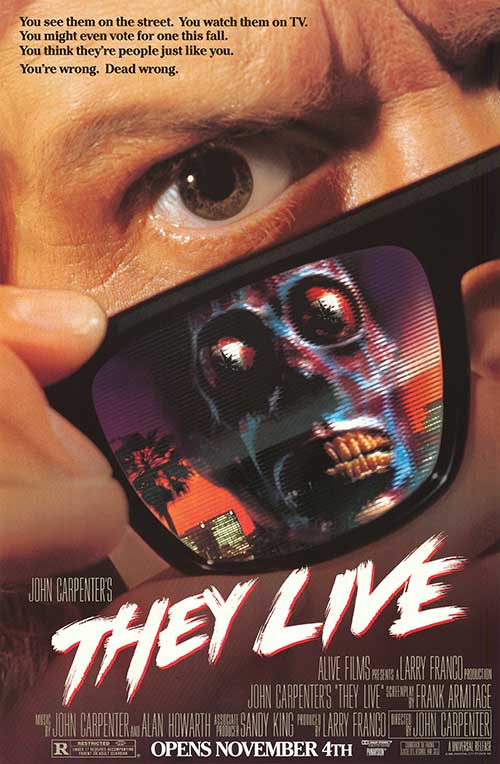

The Complete Carpenter: They Live (1988)

“What’s the threat? We all sell out every day. Might as well be on the winning team.”

“What’s the threat? We all sell out every day. Might as well be on the winning team.”

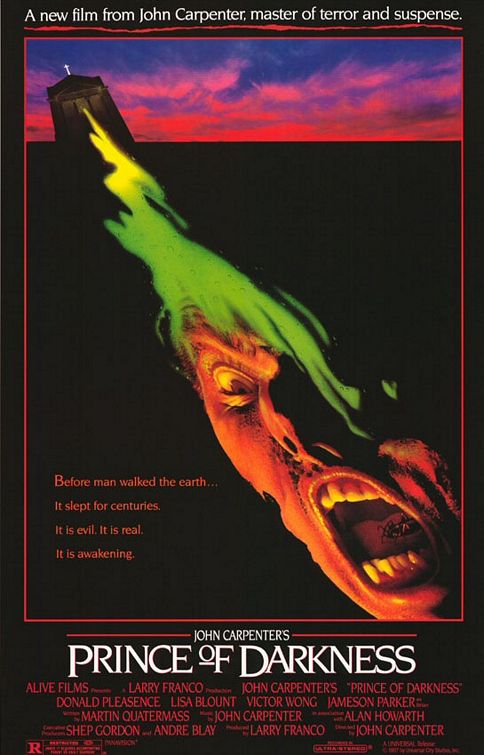

The career of John Carpenter spans four decades, but the 1980s was his special golden era. Although his ‘80s films may not have always succeeded at the box office, their run of quality is humbling: Escape from New York (1981), The Thing (1982), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and Prince of Darkness (1987). While Christine (1983) and Starman (1984) aren’t in the same tier as that group, they’re good movies audiences still enjoy today.

No other film could have closed out the John Carpenter Decade better than They Live. It’s not only the last movie he made in the ‘80s, it serves as a DO NOT QUESTION AUTHORITY curtain closer on the entirety of the decade.

The Story

Only four characters in the movie have names, so let’s get the actor attributions out of the way: Nada (Roddy Piper), Frank Armitage (David Keith), Holly Thompson (Meg WATCH TV Foster), and Gilbert (Peter Jason). “Frank Armitage” is also Carpenter’s screenwriter pseudonym, giving the impression that a fictional character in the movie also wrote it. That nicely predicts the meta-horror of In the Mouth of Madness by six years.

Nada is a drifter who’s come to L.A. searching for work. He meets another construction worker, Frank, who introduces him to the shanty town and homeless shelter of Justiceville. There’s something strange going on under the surface of Justiceville, however, and Nada discovers the shelter organizers using a nearby church to develop strange science equipment — and a bunch of sunglasses, for some reason. After a suspiciously timed police raid demolishes Justiceville, Nada escapes and finds himself in possession of the sunglasses. When he puts on a pair, he can see the disturbing truth of the world: ghoulish alien creatures disguised as the rich and powerful actually rule the planet. They’ve peppered all visual media with subliminal messages of submission to mindless consumerism to cow the human population.

But Nada is all out of bubblegum and he ain’t having this. He gets Frank to work with him — after they savagely beat each other in a back alley for five minutes — and then seeks out the underground resistance. However, they’re not only facing alien invaders, but also the human collaborators who have sold out for their slice of ‘80s yuppiedom.