There are Dragons in my Romance Novel! The rise of Romantasy

If you’ve been to Barnes and Noble lately, or on any major social media platform, there’s a word you’ve probably seen: Romantasy. It’s the marketing buzzword of 2024, and it refers to books that are the Reese’s cup of two very popular genres: Romance and Fantasy.

Did we need this portmanteau? Is it just marketing? Or is Romantasy a meaningful label?

First, some history. Because it’s me, and I can’t do a post without digging into a couple of millennia of history.

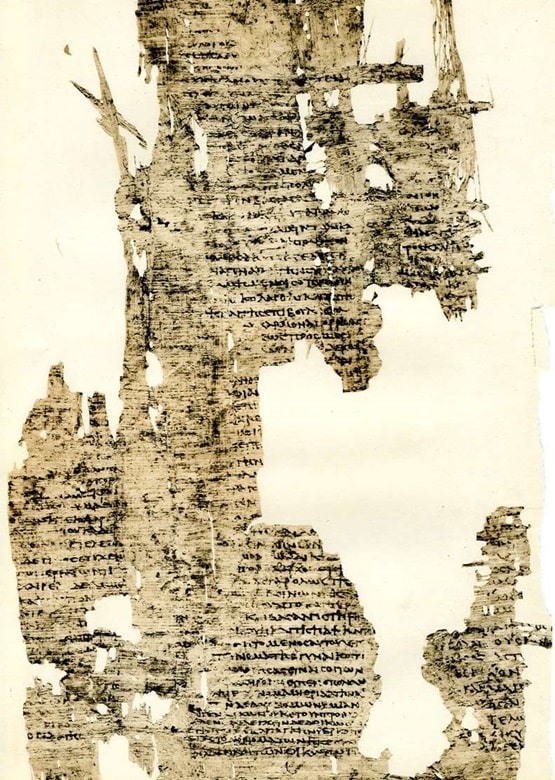

The first prose fiction we have are romances. The earliest novel we have in European literature is Callirhoe, written by Chariton of Aphrodisias somewhere between the first century BCE and the second century CE. The plot puts the modern soap opera to shame: our heroine, Callirhoe, is the most beautiful woman alive. Literally: she is Syracuse’s version of Helen of Troy. Did I mention this was set in Syracuse and that she’s the daughter of a famous hero of the Peloponnesian Wars? That’s right: our oldest known novel is a Mary Sue Historical Fiction.

And I’m just getting started. She has the very good fortune to fall in love with Chaereas, who is also by complete and total coincidence the most beautiful MAN in the world. They marry, they are expecting their first child, and Chaereas is incited by his idiot single friends into a jealous rage. He goes home drunk and kicks Callirhoe in the stomach, resulting in her death. The entire city mourns, Chaereas is very sorry, he builds a tomb in her honor (but faces no criminal charges because it wasn’t a crime to murder your wife, apparently), the entire city mourns and gives her an elaborate funeral.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, this is the end of book ONE. Of EIGHT.

A fragment of the text of Callirhoe, found in Egypt

I’ll save you the rest of the plot, which involves three fake deaths, two separate bands of pirates kidnapping our hero and heroine, two rounds of paternity guessing, the Emperor of Persia, and (Spoilers!) an ending in which Callirhoe forgives Chaereas for murdering her and they live happily ever after back in Syracuse.

This utterly unhinged work then sets the pattern for the novel from this point forward. We don’t know if this was truly the first novel ever written. But of the few novels we have, all follow the pattern of a central love story that motivates the main characters through wild adventures and ridiculous quests until they either attain their Happily Ever After or they die tragically.

So when, in the thirteenth century CE, French writers began publishing volumes of fiction written in the vernacular rather than Latin, they called them “Romances”, or books written in the Roman style. This is why Ivanhoe is subtitled “A Romance”, for example, and adventure fiction such as The Three Musketeers would have earned the title as well.

As the nineteenth century saw the explosion of popular publishing, suddenly genre got gendered. Books that focused on the adventure element of the historical romance became “masculine,” books in which there are very few female characters and those who do exist are distant paragons or prizes to be won rather than fully integrated characters. Books that focused on the “domestic” concerns such as romance and ultimately marriage became “feminine.”

This is the fundamental split in the family tree that makes up every category you see in the “Genre Fiction” half of every bookstore. Fantasy and Sci-Fi (along with Mysteries and Westerns) evolved from the Adventure side of the split, while Romance got to keep the house and the name and evolved its own ecosystem.

Ok, class, I can tell you’re all shuffling your feet. I swear, I’m getting somewhere.

When we talk about genre, what we really mean is “What rules is this story going to follow? What kind of story should I expect?”

Some of us don’t like the idea of rules for fiction. Some of us don’t like too much focus on labeling genre. But when it comes to choosing what to read and our enjoyment of a story, in any format, genre expectations are critical. When you break genre rules, you can break your audience’s trust.

Bryce Dallas Howard in The Village (Touchstone Pictures, 2004)

For example, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004). Coming after Unbreakable and Signs, expectations were sky-high for this feature. Those expectations came crashing down upon the film’s release. There are several reasons for that, but chief among them is the fact that it was billed as a Horror movie. Trailers focused on the monsters in the woods, villagers running in fear, and flickering torchlight in the darkness, all of which absolutely signaled to the audience that this was going to be a very scary movie.

But The Village isn’t the story of a small colonial era settlement under siege from monsters. At its heart, it’s the story of two people in love and the lengths they will go to save each other. (Also, the world building is too weak to sustain the twist at the end, the script was so stilted that not even William Hurt and Sigourney Weaver could save it, the entire plot around Adrian Brody’s character is gross…) Then of course at the last minute it jumps genre rails entirely in the cinematic version of a badly timed record scratch.

What made this so jarring is that any story in the “Adventure” family tree follows a fairly specific set of plot beats, and any story in the “Romance” family tree follows another.

In an Adventure story, whether it’s a western, a sci-fi, or a fantasy novel, the plot beats are set by The Quest and are acted out primarily through external events. In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker buys a droid, which shows him a clip of a movie, which sends him to Ben Kenobi, who gets him to Mos Eisley, where they find Han Solo and Chewbacca, etc. and feelings don’t really come into it.

The characters absolutely have feelings. Those feelings do matter to the motivations behind the plot. But the driver of the story is the events that unfold, and often the emotions are entirely secondary. This is why you can have entire Mystery or Sci-Fi stories in which literal or metaphorical androids are the main character. Riddick doesn’t need to have an emotional arc, and heroes of the 1980’s were notorious for their lack of any emotion other than “homicidal rage”.

In a Romance story, the beats of the story depend entirely on the internal lives of the characters. Their emotions, their thoughts, their histories all play out through events in the real world, but those events serve as external manifestations of the emotional journey the characters undergo. This is why you can have entire movies in which, according to non-fans, Nothing Happens.

In a Romance story, the beats of the story depend entirely on the internal lives of the characters. Their emotions, their thoughts, their histories all play out through events in the real world, but those events serve as external manifestations of the emotional journey the characters undergo. This is why you can have entire movies in which, according to non-fans, Nothing Happens.

If you absolutely hate the romance genre, this is one of three reasons why. From the Adventure perspective, Jane Austen’s Persuasion is a 83,000 words in which a bunch of people move house, go to a couple minor public events, and a teenager gets a bad concussion. From the Romance perspective, it’s an elaborately detailed series of emotional quests, all of which are crafted in negative space.

When it comes to modern publishing, defining your genre is about a lot more than audience expectations. Among adult fiction (AKA fiction written for adults, not, er, Adult Material Fiction), Romance is the reigning queen at 1.5 Billion dollars of the publishing market. In contrast, Fantasy brings in 500 million annually. Diana Gabaldon, author of the Outlander series, intended to sell it as a Science-Fiction story because it deals with time travel. Her agent suggested they tried to sell it as a Romance instead.

“What’s the difference?” Gabaldon asked.

“One hundred thousand dollars,” her agent replied.

But Outlander is a tricky novel to categorize. It truly is not science fiction: while it utilizes time travel as a plot device, it’s not about time travel. The characters are people who can time travel, but it’s primarily a historical fiction with an extremely strong romance element. The plot is still driven by the ridiculous series of unfortunate events the Mackenzie-Frasier clan is subject to.

In recent years, more and more novels fall into this area in between Romance and Fantasy. Previously, most of the books in this category were described as Urban Fantasy: novels which contained a modern, urban setting but with plots driven by the Fantasy elements of the story. Without werewolves, Mercy Thompson is just a mechanic. Without Vampires or a psychic ability, Sookie Stackhouse is a waitress. Those novels traditionally do have a strong romantic element to them, enough that it alienates some readers who really just want to see Harry Dresden ride a T Rex down Michigan Avenue. (And who doesn’t?)

But when Urban Fantasy became firmly established as both a fertile creative ground and as a stable market for publishers to make money, we saw a sharp rise in what is traditionally called Paranormal Romance. These are the Romance family version of Urban Fantasy, typified by writers such as Kressley Cole and Jeanette Frost. They’re the offspring of the Gothic element of genre fiction, much more Brontë and Stoker than Jane Austen, stories in which the rules of the Romance genre are followed but the plot still relies heavily on elements of the supernatural.

But what happens what happens when you have all the elements of High Fantasy – a magic system, an entirely fictional world populated by multiple sentient species, and themes of an epic struggle between cosmic forces?

In a perfectly fair world, it would primarily come down to one question:

Is the main character DATING one of the cosmic forces? If no, High Fantasy. If Yes, it’s a Romance.

But this is not a perfectly fair world. In THIS world, Romance makes the money, but Fantasy gets movie contracts and artistic respect. This is why I went into the history of the genres above and want to highlight it again:

Romance is considered feminine. Adventure Fiction is accounted masculine. Moovie makers have been reluctant to sink the kind of money that is absolutely essential to making a successful High Fantasy project into a genre that is believed to only hold appeal to women. Ticket sales hold this up: genres perceived as masculine tend to get audiences that are close to 50/50 in terms of gender. (And because we’re talking American capitalism, it’s still binary.) Movies perceived as “women’s movies” do not. In other words, “Men like sports” is a perennial stereotype, but sports movies get 50/50 audiences. Bridget Jones’ Diary did not.

However, we have a growing body of novels that truly do straddle the line between High Fantasy and Romance. The most commonly mentioned titles in this category are A Court of Thrones and Roses by Sarah Maas, Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros, and From Blood and Ash by Jennifer Armentrout. These books have been explosively popular, with Maas’ latest, The House of Flame and Shadow getting midnight release parties in most cities. Publishers (and writers!) would very  much like to leverage these successes into larger platforms.

much like to leverage these successes into larger platforms.

But even beyond marketing concerns, we run into hard genre rules that can cause real problems among readers. This is much less the case on the Fantasy side of things: if there is magic, Fantasy readers will accept a story as Fantasy. What sets Romance apart from every other genre (except perhaps mystery, which has its own hard rules) is the set of genre conventions that dictate what plot elements are allowable. These rules are both why the genre is so consistently popular and why it receives so much criticism for being formulaic and predictable.

In Fantasy, one of the main characters can die. The love interest can die. Main characters can cheat on each other and remain main characters. The main characters can save the world together and just be friends. Sex, on the page or behind a closed door, is entirely optional. And above all else, the success of the story is determined by how compelling the events are and how well the hero navigates them.

If you do any of these things in a Romance novel, you’ll have a riot on your hands.

So the territory that Romantasy is mapping now is that in which the requirements of a Romance are met. Our main characters will get a happy ending, although there is far more flexibility in what counts as a happy ending in Romantasy than there is in Romance. The romantic relationship of the main characters is a primary driver of the plot and must remain central. But it must also contain strong elements of Fantasy, and it will not be a successful Romantasy if the Adventure elements of the story do not also provide a substantial amount of the plot.

In other words, Romantasy is in many ways a return to the historical origins of the novel, in which strong elements of questing and adventure are paired with central romantic elements in narratives that balance the requirements of both genres.

I don’t know if “Romantasy” is the name we will continue to use. It is a marketing buzzword. But it’s a buzzword that is describing a very real emerging trend. Given that two of the 5 on the NYT Bestseller list fall under this umbrella, it’s a trend that I think is here to stay.

Just hopefully with a better name.

This has me wondering, though.

Does Fantasy have any hard rules? What would you say they are?

Fantasy, the oldest genre, just has one requirement: to draw the reader into a world that is distinctly other than what the reader could encounter in real life. And that not only means encounter first-hand, but also encounter in what are supposed to be factual accounts of experiences that other people have had. Where those other people could be either contemporaries or previous generations (as long as their time is not too far back). The quality that makes that world “distinctly other” could be based in magic, technology, alternate history, ancient history, a world that resembles ours but is clearly not the same, surreal happenings that violate the laws of physics as we understand them, people with “superpowers”, ghosts or other occult phenomena, etc. There’s a lot of territory.

Regarding romantasy: the impression I get is that some romance-infused fantasy is a kind of Extruded P0rn-like Substance churned out because marketing departments of publishers think it’s an easy sell. So it has some kinship to the old imitation Tolkien tome marketing fad.

And many people are under the impression that Fantasy is a kind of regurgitated infantile male wish fulfillment pulp that relies on fairy tales.

Wild, isn’t it, how people can come up with condescending and inaccurate generalizations of things they clearly know very very little about.

There is a lot of wish fulfillment stuff out there. Power fantasies where the social misfit discovers their special power that makes them a Chosen One. Sex fantasies where the protagonist gets hot sex with no messy interpersonal or social consequences. Sex fantasies where the protagonist gets hot sex which leads to a fabulous committed permanent relationship. Revenge fantasies where the social or political group that the reader doesn’t like gets stomped and humiliated. Religious fantasies where God punishes all the people the reader doesn’t like. AI will probably be writing things like this to the marketer’s specifications soon.

Thankfully that all still amounts to a fraction of the total fantasy written. Fantasy is large and contains multitudes.

That’s true of fantasy in the broad sense, or “literature of the fantastic.” But I think genre fantasy is rather narrower. Just as “science fiction” as a category includes narratives whose fantastic elements are justified by appeals to science or technology, “fantasy” as a category includes narratives whose fantastic elements are justified by appeals to myth, legend, and things that appear in myths and legends. Its ancestry probably lies in stories based on the “age of fable,” the events of Greek (and Roman) mythology, not put forth as true—nobody believed in the Greek gods, or in their appearances in, say, the Lusiads—but as traditional modes of story.

So — first I’ll say I loved the essay — it makes all kind of sense.

In direct response to this question, I think different subgenres of fantasy can have somewhat hard rules. But they’re sort of obvious , by definition stuff. Urban Fantasy is in present day more or less. High Fantasy is in a secondary world. Stuff like that. But no strict plot rules, though as with much genre fiction there is sort of a tropism towards eventual success for at least a subset of the heroes.

And of course Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories”, though far from the last word, and not exactly focused on the whole genre, is really fruitful food for thought.

Romantasy is a word created in 2022 by Hugo Roman, a french publisher belonging to the Hachette group.

Fantasy romance existe in France since the begining of the 2010. Published by small publisher or romance specialized. The fantasy romance is the most consumed niche of the fantasy today.

The problem in France is the vanishing of the masculine readership in the Millenials. And the primauty of the female readership, has led to the increasing of the romantasy.

Behing the word, it’s also to create an umbrella to mix fantasy romance and romantic fantasy. In France in the 2000 the word “bit lit” was created to mix the female driven urban fantasy and paranormal romance.

And in 2023 the word romantasy was used by Orbit and Harper Voyager who belong Hachette Group. And the group was purchased by the lat right billionnaire Vincent Bolloré. I suspect a conservative attack behind the marketing operation.

See also: video game Baldur’s Gate 3, which has a high fantasy save-the-world plot but with character romance as a main story driver for many (though not all) players.

Great read – I learned a lot about genres here. Thanks!

Terrific historical perspective, thank you for including that. I never got antsy once — and I’m masculine 😉

I’ve been cringing at this word, but you’ve now made it more palatable for me and easier to re-explain.

Great article.

Yeah, I do not like the word itself. I really hope we find a better label. It’s infantile and I think it ultimately hurts the brand. Which is a shame because I think there is some really good fiction in there.

Sarah Maas is really the defining artist of this sub-genre, and while I won’t say she’s of Jane Austen’s caliber, she’s easily on par with a Stephen King. She’s really been pegged in the Girl Lit corner, even though Throne of Glass is 100% High Fantasy with a small dose of romance.

But. There has been a recent trend on Tik Tok of women getting their partners to read A Court of Thrones and Roses, which is 100% “Romantasy”. And they genuinely like it. The dudes are discovering ACOTAR, and it’s… frankly hilarious. Because it’s a ripping good story!! And while the romance is a very big aspect of that story, the romance to action ratio is a lot lower than you’d think.

So where would Jaqueline Carey fit on the romantasy spectrum? (And count me as one of those people who while I don’t have a problem with the _idea_ of the genre, typing the word itself made me throw up in my mouth a little.)

Shamefully I’ve never made it through Kushiel, but my IMPRESSION is that it’s really not. It’s a Fantasy with strong erotic elements.