Vintage Treasures: The Bantam John Crowley

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

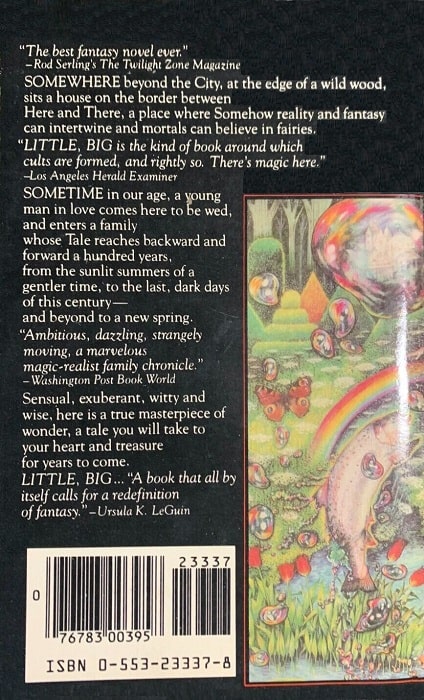

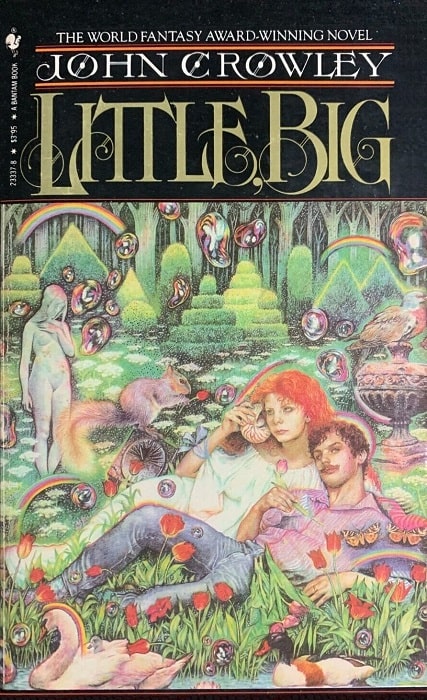

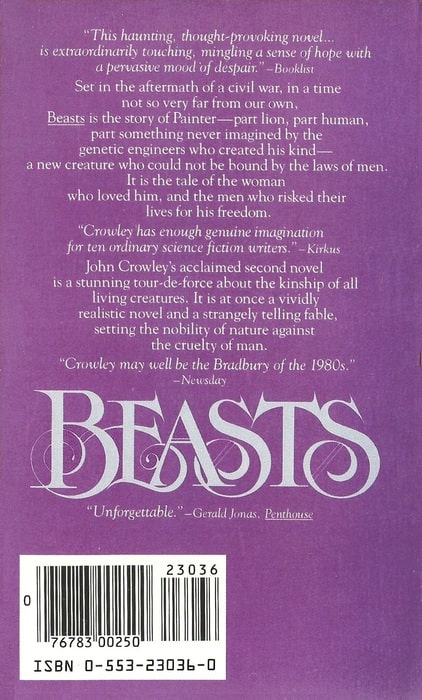

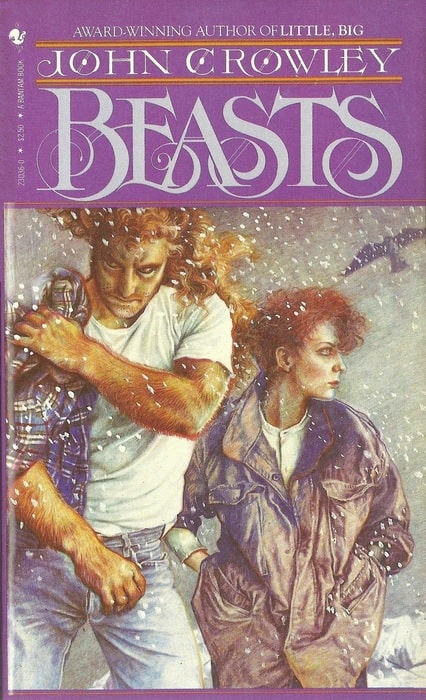

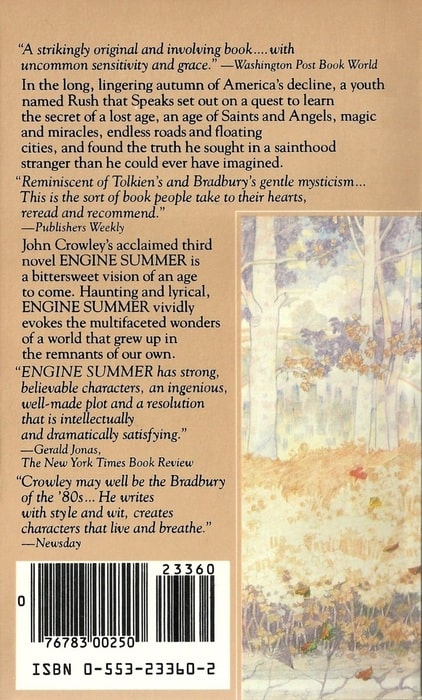

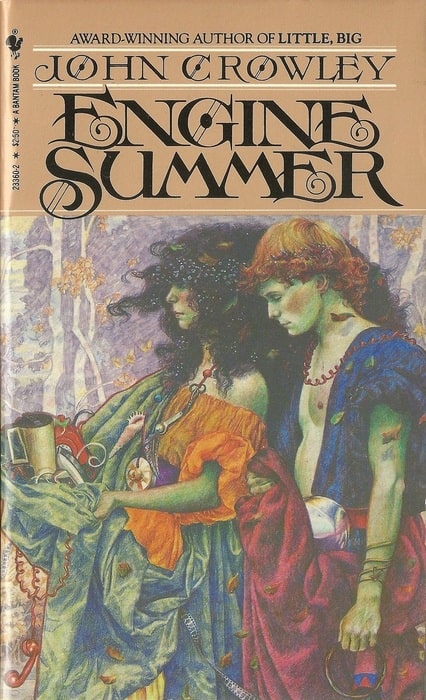

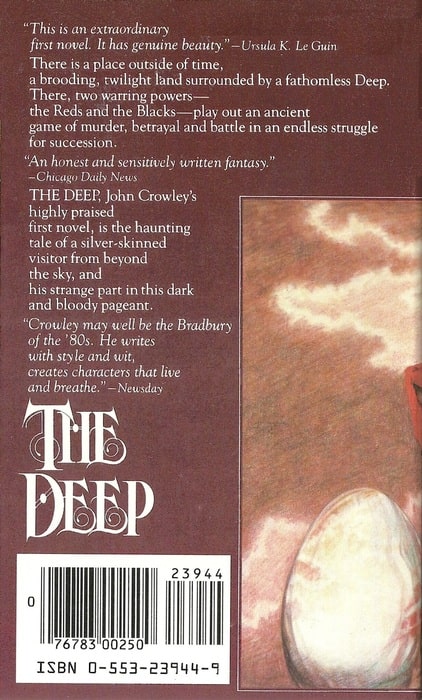

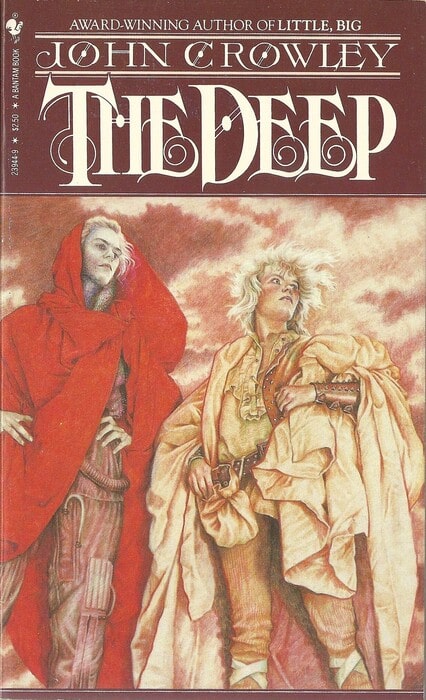

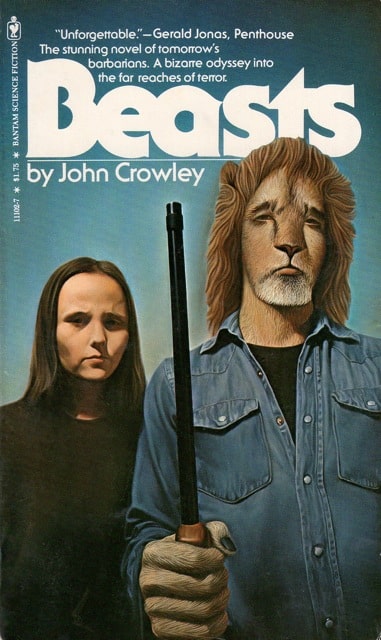

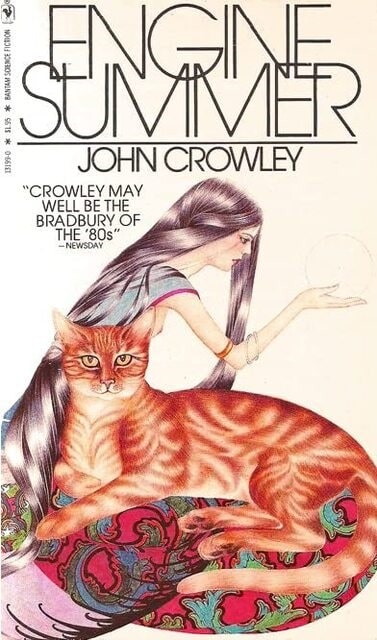

Four John Crowley paperbacks published in rapid succession by Bantam: Little, Big, Beasts,

Engine Summer, The Deep (October, November, December 1983, and January 1984). Covers by Yvonne Gilbert

In 1981 Bantam Books published John Crowley’s masterwork Little, Big, which Matthew David Surridge calls “the best post-Tolkien novel of the fantastic.” It was an unexpected hit, receiving nominations for every major fantasy prize, including the Hugo, Balrog, BSFA, Locus, and Nebula awards, and winning both the Mythopoeic Award and the World Fantasy Award. Six years later, when Locus surveyed its readers on the All-Time Best Fantasy Novel, it placed 10th. When Locus repeated the poll eleven years later, it moved up two slots into 8th place.

It’s fair to say the book’s popularity took its publisher by surprise. Bantam Books hadn’t bothered with a hardcover release — or cover art — for Little, Big; instead they published it in a nondescript trade paperback edition and snuck the book into stores under the cover of night in September 1981. They hadn’t even planned a mass market edition. It was rave reviews and word of mouth that did the rest.

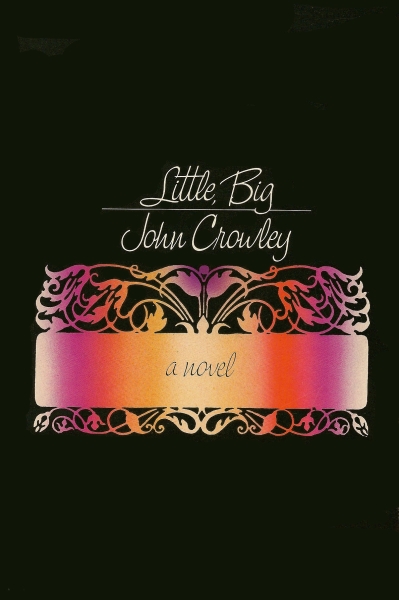

Bantam made up for it two years later, after the thunderous accolades for the book made the magnitude of their mistake obvious. They released Little, Big in a handsome paperback edition in October 1983 (two years and one month after the the trade edition) with a fine cover by Yvonne Gilbert, and in rapid-fire sequence they re-released Crowley’s entire back catalog, one novel every month: Beasts, Engine Summer, and The Deep, all with covers by Gilbert. It was the first time Crowley had ever been given any real attention by a publisher, and it helped thousands of new readers discover him for the first time.

Little, Big (Bantam first printing, September 1981)

The Bantam John Crowley editions are highly prized by collectors today. They make an attractive set of the first four novels by one of the most important American fantasists of the 20th Century, and they can be tough to find in good condition.

We’ve covered much of Crowley’s work here at Black Gate. Here’s Mark Rigney, from his 2014 article “In Praise of Little, Big.”

One of the great pleasures of adulthood is stumbling onto those unexpected moments when the world reveals that it still has secrets to impart. John Crowley’s novel Little, Big provokes in me exactly that response.

Those who have read the book fall into two distinct categories. The first group raises baffled eyebrows and perhaps does not even make it through Book One; when this group sat down to order, this is clearly not the meal they expected or wanted. The second group adores Little, Big, and can barely speak coherently about it for fear of needing to sit down suddenly or perhaps burst into a gully-washer of hand-wringing tears. I belong to the latter crowd and what I love best about Little, Big (1981) is that I have only the most limited understanding of why the book affects me as it does.

Let’s face it, I read books now as a writer, which means I am in the business of unpacking the techniques and hidden machinery of every tome I plunder — sorry, not plunder: read. I really meant to say “read.” Plunder is for pirates.

My point remains: the better the book, the more I want to plumb its mysteries, vivisect its wildly beating heart, and fully behold what makes it tick.

With Little, Big, I remain largely in the dark. In the dark, and in tears.

Steve Case delivered a fine review of The Deep to us back in 1979.

Some authors create slender, nearly flawless works of fiction. Books like little jewels on the shelf — cut just right, gleaming, standing alone. Beagle managed this a few times: A Fine and Private Place, The Last Unicorn. Goldman turned his into a movie that was nearly as good: The Princess Bride. Swanwick and Wolfe have done it with literary science fiction: Stations of the Tide and The Fifth Head of Cerberus, respectively. The Deep is a book like this: finely wrought, chiseled, alien.

Is this tiny 1975 volume science fiction or fantasy? On the one hand, the book starts with the Visitor, a damaged android who arrives in the book’s world with no memory of what he is or his mission. But the world he’s in, the culture and factions of which his ignorance provides the perfect excuse for a narrator’s artful explanation, is purely fantasy: a kingdom riven by conflict between Reds and Blacks, with a city at its center and wild wastes surrounding, ringed on all sides by the Deep.

The world, as different characters explain at different times, is a platter or a plate suspended on the Deep by a great pillar. And even when the android journeys to the edge of this world and meets the Leviathan who dwells there, when he learns the nature of the engineered conflict and how humans were first settled on the world, Crowley doesn’t ever default to pure science fiction. Even if the reader can credit a resettled humanity in the far future, reset to medieval technology with continual wars to control the population, the story still leaves you with a flat world upon the Deep. Somehow, this central oddity works; it keeps a surreal wrinkle in the heart of the world Crowley creates…

Where Crowley excels, and what makes the book so memorable, are the descriptions, both of people and scenes, running through the book. There are moments of iridescence in the language itself. The story seems almost secondary to Crowley’s love of words, an excuse for the language itself.

Read the whole thing here.

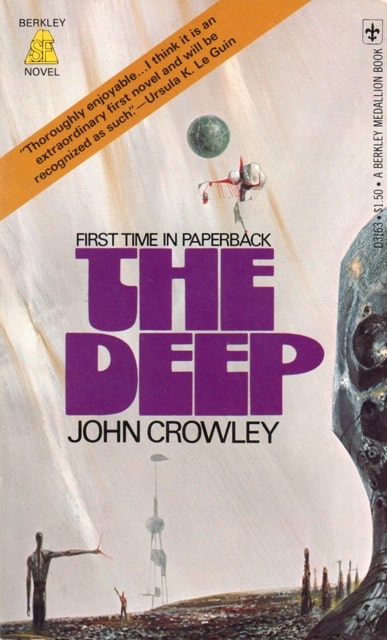

Bantam had published earlier paperback editions of Beasts and Engine Summer; The Deep first appeared in paperback from Berkley Medallion. Here’s what they looked like.

|

|

|

Original paperback editions: The Deep (Berkley Medallion, July 1976), Beasts (Bantam , June 1978), and

Engine Summer (Bantam, March 1980). Covers by Richard Powers, uncredited, and Elizabeth Malczynski

All three were originally published in hardcover by Doubleday. Here’s the complete publication history:

The Deep

Doubleday — hardcover first edition, April 1975; cover by John Cayea

Berkley Medallion — first paperback edition, July 1976; cover by Richard Powers

Bantam Books — paperback reprint, January 1984; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

Beasts

Doubleday — hardcover first edition, September 1976; cover by John Cayea

Bantam Books — first paperback edition, June 1978; cover uncredited

Bantam Books — paperback reprint, November 1983; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

Engine Summer

Doubleday — hardcover first edition, March 1979; cover by Gary Friedman

Bantam Books — first paperback edition, March 1980; cover by Elizabeth Malczynski

Bantam Books — paperback reprint, December 1983; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

Little, Big

Bantam Books — trade paperback first edition, September 1981

Bantam Books — first mass market paperback, October 1983; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

BG columnist Rich Horton posted what remains, in my opinion, the finest review of Engine Summer I’ve seen, at his blog Strange at Ecbatan.

Engine Summer [is] one of my favorite SF novels of all time… So, what came before?

Well, first, two previous novels: The Deep (1975), and Beasts (1976). I found The Deep not long after its publication, and, expecting nothing much, was really impressed. Beasts probably got more notice, but though I thought it just fine, it wasn’t as mysterious and original (to my mind) as its predecessor. Then came Engine Summer, which just detonated in my soul. Apparently it was Crowley’s fourth novel, Little, Big (1981), which detonated in everyone else’s soul… Neither should his short fiction be forgotten: the novellas “Great Work of Time” and “The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines”, as well as the short stories “Snow” and “Gone,” are thoroughly magnificent…

What is Engine Summer, then? In a way it is a bildungsroman set in a society which has abandoned even the possibility of a bildungsroman. In another way it is a post-apocalyptic elegy, resembling at a distance perhaps Edgar Pangborn’s Davy… The narrator is a young man named Rush That Speaks, who grew up in a commune of sorts called Little Belaire… it is centuries (probably) after an apocalypse called the Storm. (This is never clearly described, but it seems more an infrastructure collapse than the result of a war or of an overt catastrophe.) Most people died, but the Long League of Women had been planning how to cope for a long time, and they, it seems, enforced some sort of return to living lightly on the Earth for the survivors… They call people in their history with important stories to tell “Saints.” And along the way, Rush That Speaks decides he wants to become a Saint. The people of Little Belaire have one critical characteristic: they are Truthful Speakers (a Heinlein allusion?): “they say what they mean, and they mean what they say.”

This being a bildungsroman of sorts, Rush must leave his home. And so he does, first spending a year or so with an hermit who Rush thinks might be a Saint, a man called Blink. Then he wanders further, trying to find Dr. Boots’ List, the group Once a Day joined. There are other wonders: the Planters, source of the unearthly psychotropic fungus that Little Belaire harvests and sells; the mystery of the silver glove and the ball; the mystery of the letter from Dr. Boots; the avvengers; and the Four Dead Men. And, of course, the question of where (and who?) Rush That Speaks is as he tells his story.

The story is magnificently written, not in any ostentatious way, but supremely gracefully. The choices of names, as I’ve said, are lovely. The simple descriptions of things – some familiar to us, some new – are beautiful; and we see things like “Road” newly as Rush That Speaks describes them. And the mysteries are made – if not clear, at least perceptible – in good time, and in a very satisfying way.

Read the rest here.

|

|

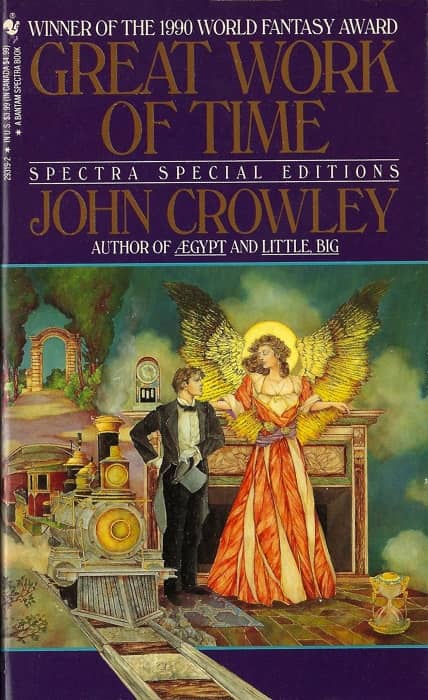

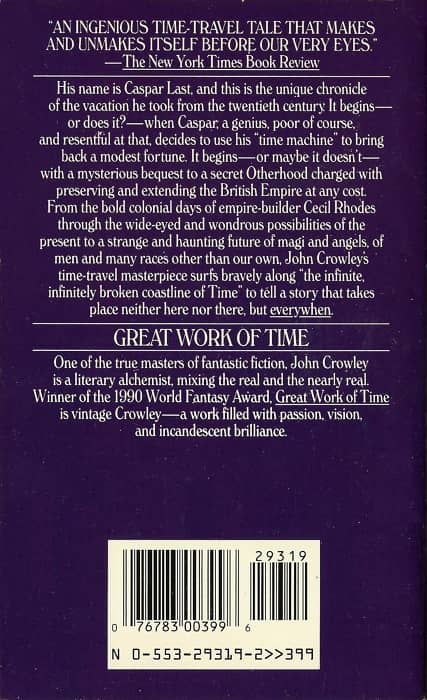

Great Work of Time (Bantam Spectra, 1991). Cover by Thomas Canty

Bantam continued to bring Crowley’s work into print in wonderful paperback editions, including his Ægypt sequence (starting in 1989), his novella Great Work of Time (1991) and the omnibus Three Novels (collecting The Deep, Beasts, and Engine Summer).

Our previous coverage of John Crowley includes:

Vintage Treasures: Great Work Of Time

A Slender, Forgotten Gem: The Deep by Steve Case

Ka

John Crowley’s Aegypt Cycle, Books One and Two by Mark Rigney

Vintage Treasures: The Deep

In Praise of Little, Big by Mark Rigney

Bad Habits by Matthew David Surridge

Here’s the complete deets on the Bantam paperbacks above.

The Deep (176 pages, $2.50 in paperback, January 1984)

Beasts (211 pages, $2.50 in paperback, November 1983)

Engine Summer (209 pages, $2.50 in paperback, December 1983)

Little, Big (627 pages, $3.95 in paperback, October 1983)

All four were published by Bantam Books with covers by Yvonne Gilbert. Little, Big remains in print today; the other three have been out of print for many years.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

I had the Bantam Little, Big years ago, and when I picked up a different edition I gave the Bantam away to someone I thought would appreciate it. Little did I know that it would eventually be “highly prized.” Oh well…

Let’s put this in perspective…. was the “different edition” you picked up the first edition?

Ha! I should be so lucky…

I’ve read a lot of Crowley and been mostly impressed, but have never been able to get through Little, Big. I just find it too fey with all the cutesy names. I’ve tried twice. My favorite is Great Work of Time.

I never read Little Big , partially out of perversity (everybody else was reading it) and partially because – like Steve – I found the basic premise too fey for its own good. I did read Aegypt, though (now retitled and part of a quartet) and thoroughly enjoyed it. I read it again a few years back and it was every bit as good as I remembered.

Haven’t read nearly as much Crowley as I should (Little, Big once, but I’m not quite sure I grokked it), but I do love those covers.

I have a pile of John Crowley novels all queued up for re-reading. He’s definitely one of our best.

I will confess I still prefer the original MMPB covers for THE DEEP and ENGINE SUMMER. I mean, you can never go wrong with Richard Powers; and Elizabeth Malczynki’s cover for ENGINE SUMMER is just gorgeous. (Though I don’t like her cover for Le Guin’s BEGINNING PLACE all that much.) It seems she worked for Bantam from 1977 or so through 1981, and did covers for them at that time, including for some of McCaffrey’s Pern books. She still does art — has a site called The Dragon Studio — but the ISFDB doesn’t show illustrations after 1981.

It’s true, Elizabeth Malczynki’s cover for ENGINE SUMMER is gorgeous.

But I’m SUCH a sucker for matching art (and cover design) on my bookshelf. To me the Bantam editions will always be definitive.

I have the original Bantam edition of LITTLE, BIG and I like it too, even relatively plain as it is. I am awaiting delivery of the deluxe new edition, heavily illustrated, before I commence a long overdue reread.

Also — one of my great regrets — though not my fault — is that the panel discussion we had at Boskone a few years ago about Crowley — with Faye Ringel and a couple more people — was not successfully recorded. (There was a videographer but he never posted the video — not sure what happened.) I remember discussing “Great Work of Time” and ENGINE SUMMER and being brought to tears somewhat to my embarrassment. But Crowley does that.

The Beginning Place was called Threshold over on this side of the pond. The cover art was by Alan Cracknell. Julek Heller did the cover for Little Big.

https://biblio.co.uk/book/little-big-crowley-john/d/738337497?aid=frg

https://www.mwbooks.ie/pages/books/6950/ursula-k-le-guin/threshold