The Timeless Strangeness of “Scanners Live in Vain”

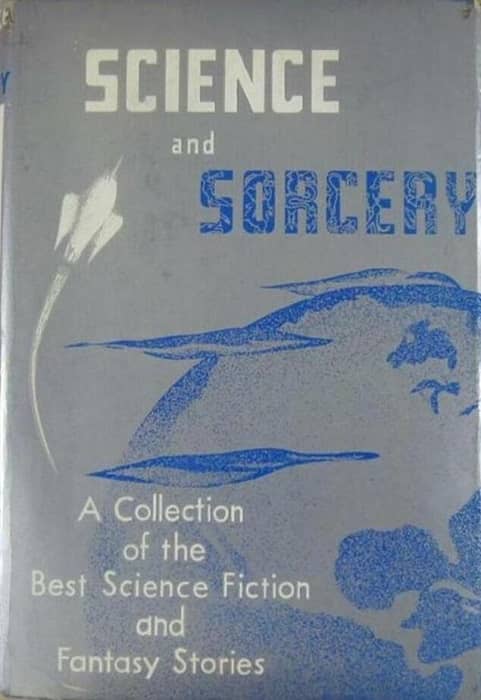

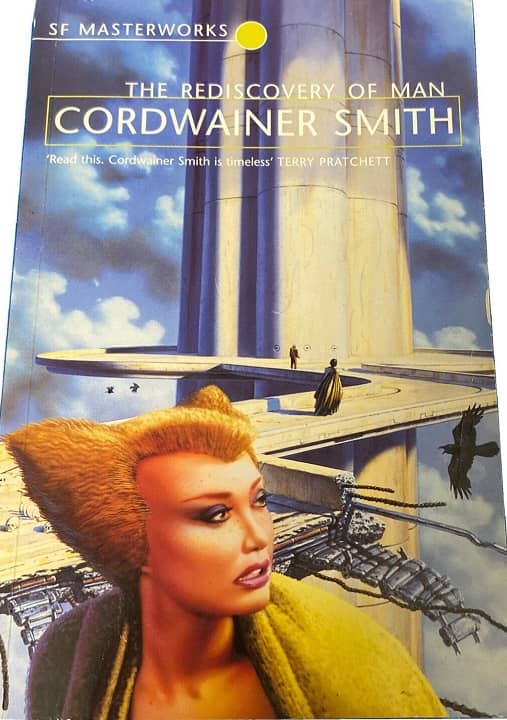

Fantasy Book No. 6, January 1950, first appearance of

“Scanners Live in Vain” by Cordwainer Smith. Cover by Jack Gaughan

I recently had occasion to reread Cordwainer Smith’s Science Fiction Hall of Fame story “Scanners Live in Vain.” This was probably my fifth rereading over the years (soon followed by a sixth!) — it’s a story I’ve always loved, but for some reason this time through it struck me even more strongly. It is a truly great SF story; and I want to take a close look at what makes it work.

In this series I often discuss the background details of a story’s publication history, and of its author, first — and these are especially interesting in the case of this story; but I don’t want to bury the lede either. So I’ll discuss the story first, and then go over the history of its publication, and its author’s career. As ever in these essays, the discussion will be rife with spoilers.

“Scanners Live in Vain” opens with a famous pair of sentences:

Martel was angry. He did not even adjust his blood away from anger.

That second sentence is beautiful SF “incluing” (to use Jo Walton’s wonderful coinage): showing us within the text something strange about this future. The paragraph quickly makes it clear that Martel can see but not hear: “he… could tell by the expression on Luci’s face that the table must have made a loud crash;” and that he cannot feel his own body, or feel pain: “he looked down to see if his leg was broken.” And we learn that Martel is a Scanner, and that a Scanner scans instruments in his “Chestbox” to confirm his health. And that a Scanner can talk but can’t hear himself talk, and thus his voice is unpleasant to other people – in Martel’s case particularly his wife Luci.

The next line introduces the first actual new word: “I tell you, I must cranch.” (The word has become a part of the vocabulary of some SF readers!) “Cranching,” we learn, is a process by which a Scanner temporarily regains access to his sensorium — as Martel puts it “to be a man again, hearing your voice, smelling smoke. To feel again…” Alas, it is dangerous to cranch too often, and Martel has recently cranched.

|

|

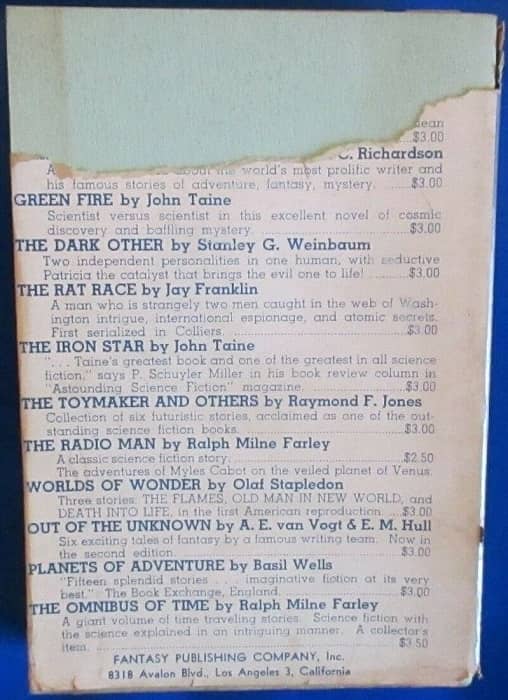

Science and Sorcery (Fantasy Publishing, 1953), first reprint of “Scanners.” Cover art by Crozetti and Walter

What follows is a sweet domestic scene, interlaid with more hints of future strangeness. Luci deploys the Cranching Wire after Martel asks her by writing with his “Talking Nail.” Now Martel can hear and feel and smell. Martel revels in his senses, especially smell (a Proustian touch?):

The crisp freshness of the germ-burner, the odor of the dinner they had just eaten, the smells of clothes, furniture, of people themselves…

(I loved the SFnal reference to a “germ-burner.”) He also loves the sounds – he sings a Scanner song, delights in the swishing of Luci’s dress. Soon Luci offers to play some new “smell recordings,” including one of a lamb chop, and asks Martel to identify it.

This is a delicious passage (pun intended) — conveying at once Martel’s rare experience of smell, the apparent vegetarian diet of Earth at this time, the rarity of “Beasts” on Earth, and, crucially, Martel’s association of the smell of burning meat with phantom recollections of injured men he had tended in the “Up-and-Out” on a burning spaceship. And we learn more about the Scanners:

The bravest of the brave, the most skillful of the skilled… protectors of the habermans… They make men live in the place where men desperately need to die.

We also learn of Martel’s agonized perception of his relationship with Luci — she, he feels, is chained to a man who is mostly not a man. “A man who has been killed and left alive for duty.”

|

|

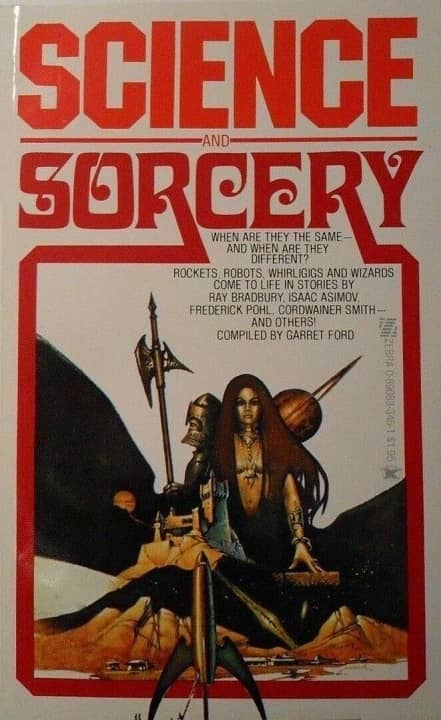

Science and Sorcery (Zebra Books paperback reprint, May 1978). Cover art by Tom Barber

This opening sequence, less than 20% of the story, seemed to me on this reread incredibly dense, extremely powerful. We don’t know much of this until later (perhaps in some cases until we read later stories) but the information hidden here, about the nature of the Instrumentality, about the history of Earth from now until the Second Age of Space (that is, the time of the Scanners) is remarkable. And, again, the more we know about habermans, about Scanners, about the “Up-and-Out,” about why Scanners live in vain, the more powerful this becomes.

And then comes the call that signals the change of everything for Scanners. An emergency call from the leader of the Scanners, Vomact. (A family that resonates throughout Smith’s history of the Instrumentality.) A Scanner who has cranched is normally not allowed at a Scanner meeting, but this is an emergency. Everyone must come. So, still cranched, Martel comes to Central Tie-In for the meeting. We are introduced to two of his closer Scanner friends, Chang and Parizianski. This scene effectively portrays Scanners as a group, a Confraternity – they way they look and act, especially in contrast to Martel’s cranched state, the way they communicate (lip reading and the Talking Wire), and their ritualistic reinforcement of their loyalty, their duty, and their separation from both the lowly habermans (“the scum of mankind … the weak, the cruel, the credulous, and the unfit.”) and the “normal” humans: the Others, in Scanner terminology.

To clarify a bit: Scanners are men who have volunteered to undergo the Haberman process — to have their sensorium (except for sight) detached from their consciousness. As such, they monitor the habermans — criminals who have been sentenced to the near death of the Haberman Process as an alternative to the death penalty. The Scanners scan the instruments of the habermans to make sure they are not overstressing their bodies — and they scan themselves too. Thus:

Habermans we are, and more, and more. We are the chosen who are habermans by our own free will… All mankind owes most honor to the Scanner, who unites the Earths of mankind…

Why are habermans and Scanners needed? Because of the First Effect of Space travel: the Great Pain of Space. The only way to survive is to feel nothing. And so habermans are made to labor on spaceships while human passengers sleep through the journey. And since without feeling habermans would hurt themselves, and without supervision they would not work, Scanners must keep an eye on their instruments for bodily damage.

|

|

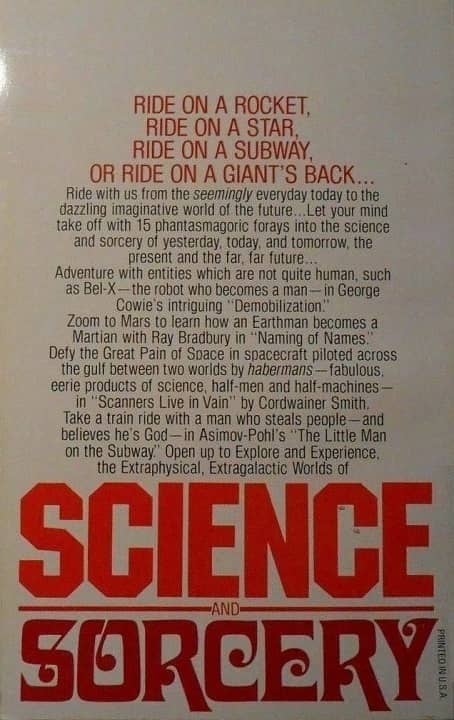

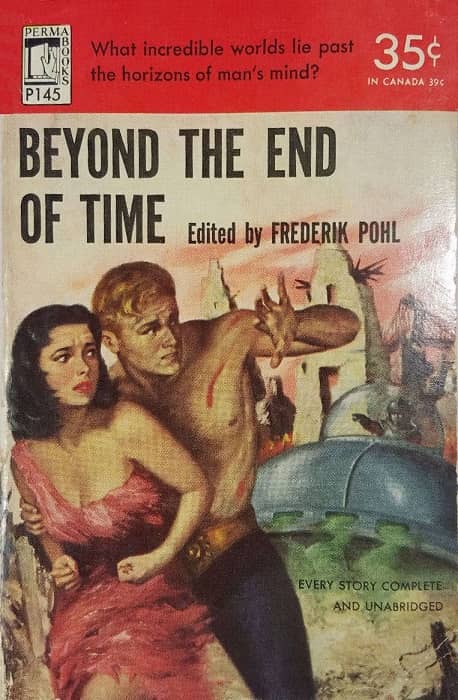

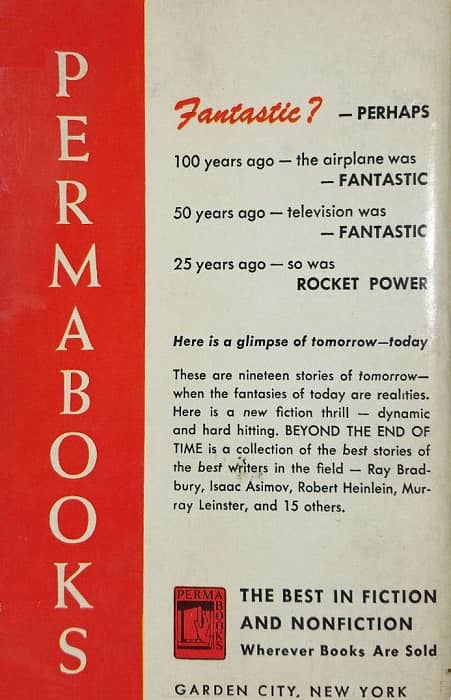

Beyond the End of Time, edited by Fred Pohl (Permabooks, January 1952), first mass market reprint of “Scanners.” Cover art uncredited

But now we learn the reason for the meeting: a man named Adam Stone has developed a process to insulate unmodified humans from the Pain of Space. Thus, Scanners live in vain. And Vomact, arguing that either Adam Stone is lying (his solution doesn’t work) or that even if it does, the loss of status of the loyal and heroic Scanners will bring disorder, even war, to Space. And he invokes the Scanners’ “secret duty.” If the code of the Scanners is violated, no ships go out, and if no ships go out:

The Earths fall apart. The Wild comes back in. The Old Machines and the Beasts return.

And the secret duty says that those who violate it must die. So, “Adam Stone must die.”

There is much to unpack here. Smith’s prose in this story doesn’t fully achieve the incantatory power of his later work, but it is tremendously forceful, intense. And it does reach incantatory heights in this sequence, with the repeated invocations of the Scanners’ duty, and their law. The references to the past of this distant future — the Old Machines, the Beasts, the Unforgiven, the Manshonjaggers — are powerful, intriguing, ambiguous. This sequence also shows — and we see this in many Instrumentality stories — the harsh nature of the Instrumentality. The punishment meted out to the habermans is horrifying — forced labor in the Up-and-Out, disconnected from one’s sensorium, followed only by death. (And of what are the habermans guilty? They are “criminal or heretics” or just “credulous” or “unfit” (italics mine) — perhaps some are murderers, but some are only guilty of thought crimes. And they are not simply executed, but tortured via forced labor.)

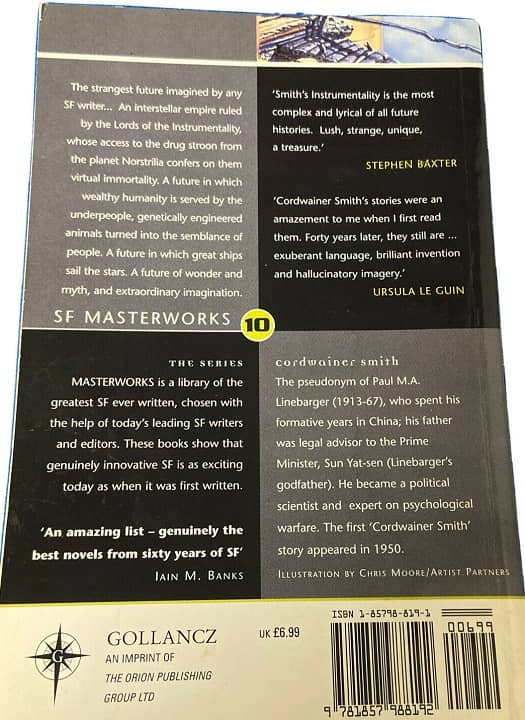

Table of Contents for Beyond the End of Time

The Scanners as a group are immediately ready to execute Vomact’s command, but a few resist. One is Parizianski, who wonders “What if Stone has succeeded?” — this means freedom for the Scanners: “Men can be men” — and mercy for the habermans: “The habermans can be killed decently and properly, the way men were killed in the old days.”

In his cranched state (and also perhaps because he is married — apparently (and not surprisingly) this is all but unheard of for Scanners) Martel feels the wonder and hope of this message deeply. The story lets Martel meditate, for a moving few pages, about his history as a Scanner, the horrors he’s seen, the pain he’s felt, his agony over what Luci has to put up with in their marriage. But in the end only he and a few more vote against Vomact, and the order is issued — Adam Stone must be killed. Martel’s protests are ignored, and even his friends who voted with him, come to support Vomact, out of loyalty to the discipline of the Scanners.

This leads to the inevitable conclusion — Martel betraying the Scanners, rushing to Adam Stone’s place and learning of his success and how he managed it, and then confronting the Scanner sent to kill Stone, who of course turns out to be his friend Parizianski. The conclusion — Martel waking, fully human, in Luci’s company and hearing from her the happy news about the Scanners, with only one exception, is powerful and moving again.

This is a long story (perhaps 13,000 words) but it proceeds at a fierce rush. And for me, the first time through, it was easy to see the surface, and be excited and thrilled by the basic idea, but miss or forget the depths — the weird hints of the Instrumentality’s past; the dark realization that the quasi-Utopian Instrumentality is brutal at its core; the alternately lovely and severe evocations of the life and work of a Scanner and of Martel’s feelings under the Cranching Wire; the almost scriptural declarations at the Scanners’ meeting; the delicious revelation of what Adam Stone did to shield living humans from the pain of space (oysters in the ships’ outer hulls!) and the crushing truth of what Martel had to do to save Adam Stone.

|

|

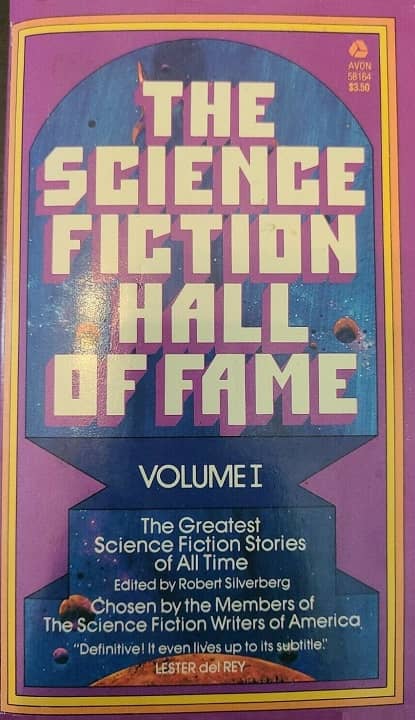

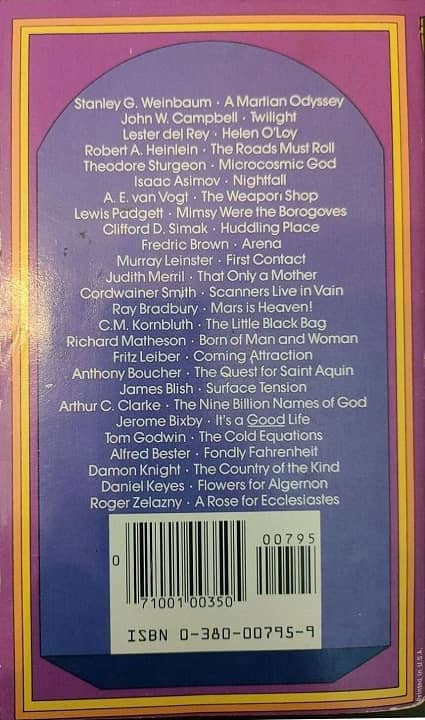

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, edited by Robert Silverberg (Avon, July 1971).

The prose, as I have said, is not as well-developed as in the best of Smith’s later stories, but it is vigorous and evocative – I have quoted some passages but not the best – I loved, for instance, Martel’s comment upon briefly seeing the stars:

The stars are my enemies. I have mastered the stars but they hate me.

Another nice touch is the phrase “the dark inward eternities of habermanhood.” The sketch of Martel’s relationship with Luci – and his memories of their courting – is sweet and affecting. The denseness of “incluing” – even minor details of that future such as traveling from place to place by flying – is remarkable. This is a story that improves and deepens upon rereading, as with most great stories.

And where did it come from? “Scanners Live in Vain” was “Cordwainer Smith”‘s first published story. He wrote it in 1945, submitted it to all the extant SF magazines, and finally let it go to a very low-end semi-professional venue, Fantasy Book, edited by William Crawford. (Some sources say he wasn’t even paid by Crawford.) Crawford’s efforts in the SF field were actually moderately significant — he published four magazines — Marvel Tales, Unusual Tales, Fantasy Book, and Spaceways.

It’s worth noting that the issue of Fantasy Book featuring “Scanners Live in Vain” also featured stories by Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl (in collaboration), Stanton Coblentz, and Alfred Coppel — all names of at least moderate weight in the field. And Frederik Pohl’s involvement, in particular, seems to have proved important for Smith’s career. (I should add that for most of his efforts, including Fantasy Book, Crawford was collaborating with his wife Margaret, and they often used the joint pseudonym Garret Ford.)

|

|

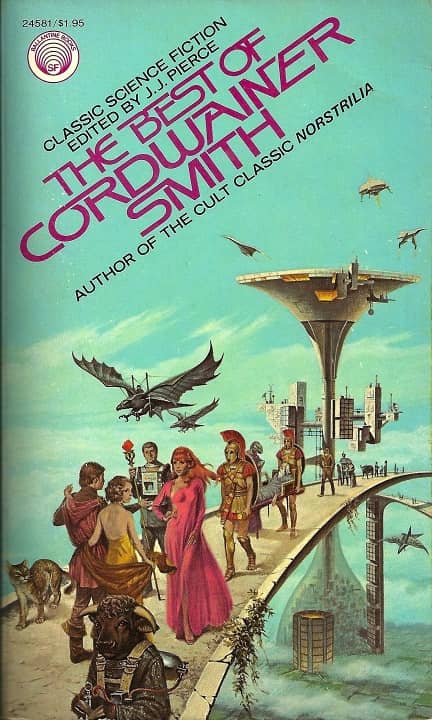

The Best of Cordwainer Smith (Ballantine, September 1976). Cover by Darrell Sweet

By the way, there’s a reproduction of Paul Linebarger’s cover letter to his submission to Fantasy Book. It’s addressed to “Mr. Ford” – obviously Linebarger didn’t know about the Crawfords’ editorial pseudonym. The letter suggests that “Scanners Live in Vain” is more “literary fiction” than “pulp,” and that perhaps as Fantasy Book is “off-trail” that might appeal to them. He says they can find him in Who’s Who, with reference to his already published books (at that time, mostly or entirely non-fiction.) And he includes $3.00 for a subscription to the magazine (including back issues) — there’s some advice for an aspiring writer!

It’s not clear that “Scanners Live in Vain” had any broad immediate impact. After all, Fantasy Book was a marginal magazine. But the story did get reprinted twice in the next three years after its first appearance. One reprint was in Science and Sorcery, an anthology edited by “Garret Ford,” which is to say, William (and probably Margaret) Crawford, and published by the Crawfords’ company. It consisted of stories from Fantasy Book and a few originals (one suspects, stories submitted to Fantasy Book but not published before the magazine folded.) There were only 800 copies printed of this edition.

But the other early reprint was in an anthology edited by Frederik Pohl, Beyond the End of Time. This was a paperback from a then respected publisher, Permabooks, with presumably a big print run. It featured writers such as Asimov, Heinlein, Clarke, and Bradbury; and such major stories as Clarke’s “Rescue Party,” Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” and C. M. Kornbluth’s “The Little Black Bag.” I suspect it was this anthology that first brought “Scanners Live in Vain” to a wide audience. (And — good as the stories I’ve mentioned are, “Scanners Live in Vain” is even better.)

The question is — how did Pohl know of this obscure story, only published in a marginal magazine? And the answer, I imagine, may be that Pohl also had a story in that issue of Fantasy Book! (This was “The Little Man on the Subway,” co-written with Isaac Asimov, and published as by “James MacCreigh.”) (Robert Silverberg, just 15 years old when the story came out, reports that he did find “Scanners” in Fantasy Book, and was immediately taken by it — and in fact it was Silverberg who arranged for the first Cordwainer Smith collection, and selected its contents. This was You Will Never Be the Same, from Regency Books in 1963.)

Of such happenstance as Pohl having a story in that issue of Fantasy Book, I think it is possible that a major career was born. For not only did Pohl reprint “Scanners Live in Vain,” a reprint that likely led to its selection for The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I; but Pohl didn’t forget the mysterious “Cordwainer Smith.” And in 1955, according to Mike Ashley’s Transformations, Pohl “encouraged” “Smith” to submit a story (“The Game of Rat and Dragon”) to Galaxy, then edited by H. L. Gold. Not long after, Pohl was working for Gold at Galaxy, and he wanted to get more stories from Smith. To that point, as far as I know, his only contact had been through Smith’s agent, Forrest J. Ackerman. (A less Linebarger-like figure than Ackerman I can hardly imagine!)

|

|

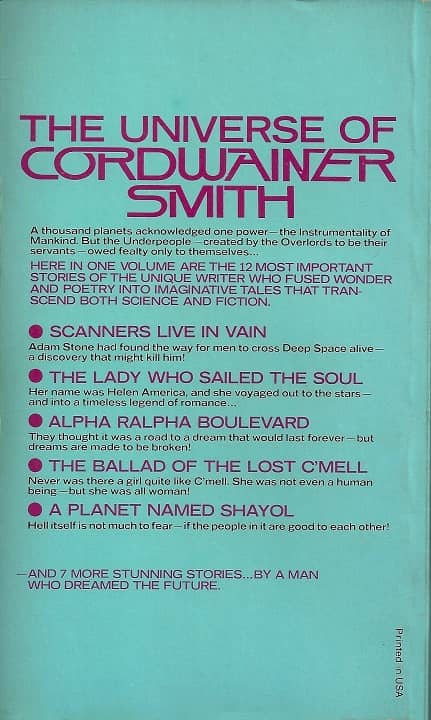

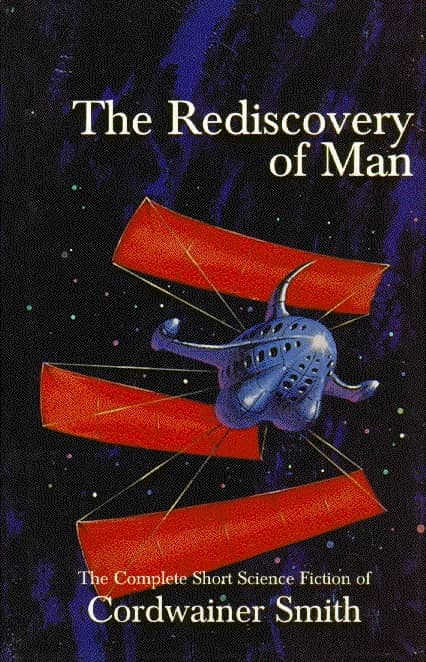

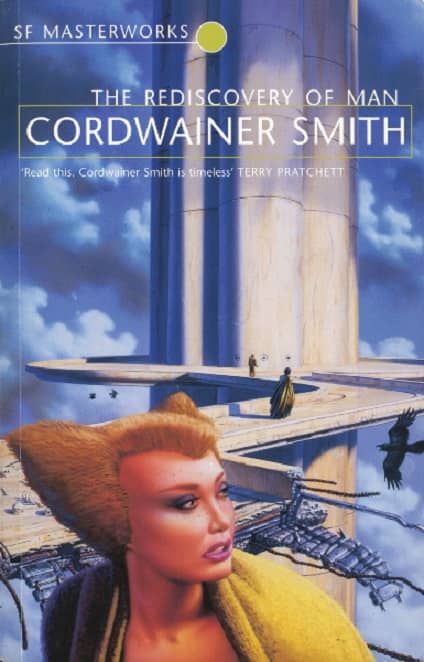

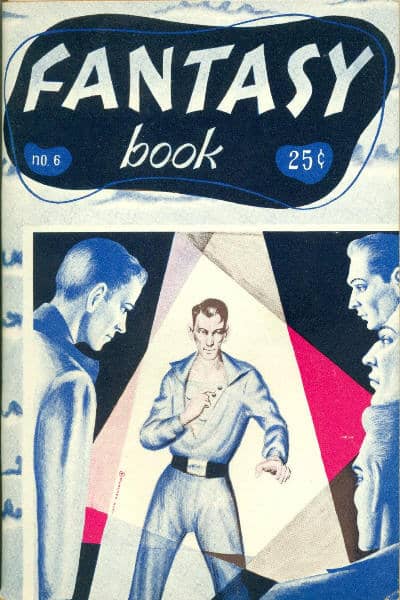

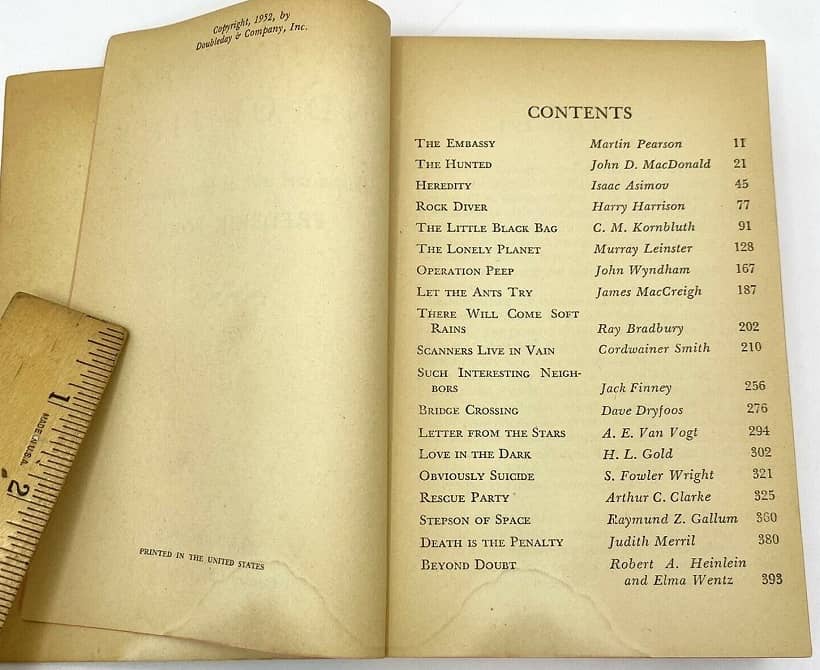

The Rediscovery of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of Cordwainer Smith, NESFA Press edition

(June 1993) and SF Masterworks edition (May 1999). Covers by Jack Gaughan and Chris Moore

But, Pohl says, he got a call out of the blue, from a man calling himself Paul Linebarger. Pohl was a bit confused until Linebarger said “I write science fiction as Cordwainer Smith.” Pohl ended up buying a dozen of Linebarger’s stories, mostly for Galaxy and If after he took over the editing reins from Gold, but also for his original anthology Star Science Fiction #6. (I’ve talked previously in this series of essays about Pohl’s role in James Tiptree, Jr.’s, career; and also about his role publishing Samuel R. Delany’s great novella “The Star Pit.” Add his advocacy for Delany’s Dhalgren, which he published at Bantam despite his bosses’ skepticism about the commercial prospects of a very long rather experimental novel; and you can see continued evidence for the importance of Pohl’s editing to the history of SF.)

I spent some time comparing the two versions of the story I have to hand, one from The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One; and one from The Best of Cordwainer Smith. The first was published in 1970 but seems to be directly based on the Fantasy Book printing. The second, from 1975, has some editorial changes, minor but interesting. Either the editor of The Best of Cordwainer Smith (J. J. Pierce) or perhaps a copy editor at Ballantine, chose to eliminate the numbered section divisions in the original; and also chose to eliminate the eccentric capitalization Smith used for some of the unique aspects of the story – he capitalized such terms as Cranching Wire, Up-and-Out, the Great Pain of Space, the Talking Nail, the Tablet, and so on. In both these cases I think the text of the original version is actually to be preferred.

The later version also makes a couple of very slight word changes (substituting “kin” for “kith” twice – in one case correctly, in the other case I think mistakenly; and also cleaning up and clarifying one phrase: “Most meetings that he attended seemed formal heartening ceremonial” becomes “Most meetings that he attended seemed formal, hearteningly ceremonial” which I think is an improvement; and also changing the spelling of “Manshonjagger” to “manshonyagger,” which I think was done for consistency with later Instrumentality stories.)

|

|

The Rediscovery of Man, SF Masterworks edition (May 1999). Cover by Chris Moore

I note as well that the version in The Rediscovery of Man, the exceptional NESFA Press edition collecting all of Cordwainer Smith’s short SF, adopts the original version with only the “formal, hearteningly ceremonial” change. I think that edition should be considered definitive.

“Cordwainer Smith,” as noted above, was a pseudonym, for Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger. And Linebarger is a remarkably interesting man aside from his “Cordwainer Smith” side. He was born in 1913, his father a lawyer who was advising Sun Yat-Sen, the first President of the Republic of China after the overthrow of the Emperor. (Sun Yat-Sen, in fact, was Paul Linebarger’s godfather.) Linebarger’s family moved often, and he lived in several countries, and by adulthood was fluent in Chinese, English, and German. He held a Ph.D. in Political Science from Johns Hopkins, and taught at Duke. He was an expert in Far Eastern affairs, and during the Second World War served for the Army in China, and became close to Chiang K’ai-Shek. He was a leading expert in psychological warfare, and called himself a “visitor to little wars,” advising our allies about propaganda.

Linebarger first married in 1936, and had two daughters. After a divorce, he remarried. His second wife, Genevieve, collaborated on several of his stories, and apparently one of the posthumously published “Cordwainer Smith” stories, “Down to a Sunless Sea,” is by her alone. Linebarger also published three novels before any of his “Cordwainer Smith” stories appeared: Ria (1947) and Carola (1948), both as by “Felix C. Forrest”; and Atomsk (1949), a spy thriller published as by “Carmichael Smith.”

He published poetry as by “Anthony Bearden.” He finished three other novels in the late 1940s, General Death, Journey in Search of a Destination, and The Dead Can Bite. They have not been published, and I know nothing about them. The other three 1940s novels seem reasonably well regarded by “Cordwainer Smith” fans, though I have not yet read them myself.

Smith became something of a sensation in the SF field after Pohl’s rediscovery. The wide revelation of his identity, after his death at only 53 in 1966, added to his mystique, and a few additional stories plus various collections dribbled out, culminating in 1993 with the massive NESFA Press collection of his complete short fiction, The Rediscovery of Man. He was never really forgotten (and Baen published new editions of his fiction in the 2000s) but in a way he seemed to fall into a slight eclipse for a while, not exactly dismissed but regarded by some as an outlier, sort of a curiosity.

The Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award awarded to Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore in 2004

In this context the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award, founded by his daughter Rosana Hart in 2001 (and sponsored by the Cordwainer Smith Foundation), is interesting, for it aims to bring worthy SF writers who have fallen into some degree of obscurity into greater notice. (Full disclosure: as of 2021, I am part of the jury for that award, along with Steven H Silver, Grant Thiessen, and Ann VanderMeer.)

At any rate, it seems to me now that Smith — though never forgotten — is recently being to some extent rediscovered again, and his importance only seems to be growing. It is astonishing, truly, that his stories, written between 1945 and 1965, still seem fresh, still seem, as Robert Silverberg once suggested, to be the work of a time traveler from the distant future, telling of events from his past. Or perhaps it is only I who have rediscovered him — everyone else never forgot — but my recent rereading, not just of “Scanners Live in Vain” but of stories like “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard,” “Drunkboat,” “No, No, Not Rogov!” and others, has been remarkably rewarding.

It is clearer to me now than ever before how original Cordwainer Smith’s work was, and remains, how emotionally powerful he could be, and how sneakily influential he was.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a review of Saint Death’s Daughter by C. S. E. Cooney/ His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written nearly two hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Fantastic article. This story is so, so fine, and even in its excellence an amuse-bouche to the extraordinary feast that is the short fiction of Cordwainer Smith.

“to be the work of a time traveler from the distant future, telling of events from his past.”

Or the work of a soul split between scientific work in contemporary America and science-fictional adventure on a distant planet (perhaps called Barsoom?). At least if the speculation (started by Brian Aldiss in his history of sf, The Billion-Year Spree) is true that Dr. Linebarger was the real-life figure behind “Kirk Allen”, the dual-souled physicist of “The Jet-Propelled Couch”, a psychiatric case related by analyst Robert Lindner.

Whatever the truth, the existence of the stories is (as you noted, Mr. Horton) another debt we sf readers owe to Frederik Pohl, himself closing in on qualification for the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award, alas. (And is there an award in genre fiction with a better name?)

I’ve read various articles about the theory that Linebarger was “Kirk Allen” and at this point I’m leaning towards skepticism. Probably we’ll never know for sure.

Excellent article.

Cordwainer was easily the most interesting writer of speculative fiction in the too few years he was active. Of his stories I’ve read so far, apart from Scanners the story that impressed me most was Mother Hitton’s Littul Kittons. I have a feeling Frank Herbert too was impressed with that story…

I read “Scanners Live in Vain” in TSFHoF Volume 1 back in like 1989– I remember having a little trouble getting into it because it was so timelessly strange, but it was interesting enough to keep me engaged. It is also one of those stories that really carved out a place in my memory– a true classic!

And, Rich, Basil Wells, an old hand at sf as well as other sorts of fiction by 1950, shouldn’t be overlooked…the purchaser of the issue would have several inducements from name-recognition off the TOC alone, even before wonder what this Shoemaker Craftsman person might have cobbled together.

[…] A VISIT TO THE INSTRUMENTALITY. Rich Horton tours the worldbuilding of Cordwainer Smith in “The Timeless Strangeness of ‘Scanners Live in Vain’” at Black […]

[…] A VISIT TO THE INSTRUMENTALITY. Rich Horton tours the worldbuilding of Cordwainer Smith in “The Timeless Strangeness of ‘Scanners Live in Vain’” at Black […]

The 1970 Berkley edition of “You Will Never Be The Same” has “manshonyagger” and “formal, hearteningly ceremonial”. A note on the Acknowledgments page says “Chapters of this book originally appeared as magazine pieces and have been specially revised for inclusion here” , for what it’s worth.

Thanks! (Sorry I didn’t see your comment earlier.) This is good information.

[…] agent, who certainly knew his identity. Rich Horton has an excellent piece at Black Gate, “The Timeless Strangeness of ‘Scanners Live in Vain‘”, 2022, which reveals a lot about how information on Cordwainer Smith started to be […]