Diceless Adventuring: Bounty Hunter

For the past three years, Kickstarter has had an annual event known as Zine Quest:

Our annual Zine Quest prompt bestows creators with this valiant mission: Bring your RPG to life with maps, adventures, monsters, comics, articles, and interviews. To participate, launch a two-week project for a single-color unbound, folded, stapled, or saddle-stitched RPG zine on A5 or smaller paper.

The zines tend to be small in size, and thus relatively inexpensive. This year, I participated, purchasing a few supplements for Mothership (you can read my review of this RPG here) and Mörk Borg along with a few full-fledged RPGs. One of these was Bounty Hunter, which I received in PDF and hard copy a few weeks ago.

The game was created by Guy Sclanders, a personality on YouTube who offers often excellent advice for gamemasters (GMs) and reviews on his How to Be a Great GM channel. Bounty Hunter focuses on an original setting and a non-traditional mechanic for RPGs: it is diceless.

In the Kickstarter campaign, Sclanders wrote:

I wanted to make the easiest-to-play TTRPG ever. It had to have some mechanics, it had to inspire awesome adventures, and… it had to have zero math, no dice, and just be a blast to play regardless of the player’s TTRPG experience.

Instead of dice to determine success or failure, the players and GM spend action points (AP) to complete actions, do tasks, and anything else that would require dice rolls in more traditional games. Spend the AP and the task succeeds. The exceptions to this automatic success are when the opposing player (whether player characters [PCs] or non-player characters [NPCs]) spend more AP.

The basic game scenes are divided into Freeform and Dramatic. Freeform are those times when the order of character actions is not generally important. Dramatic is when they are. In either case, players may have to spend AP to complete tasks, but Dramatic scenes have a bit more structure.

Dramatic scenes are divided into two phases. Players can choose to act in the first phase or wait until the second. If the former, they must spend 1 AP to act. Making an attack, defending against an attack, using a skill, and other such things cost an additional 1 AP to do, regardless if the player chose to “pay” to go in the first phase or not. These are called significant actions. Free actions include saying a few words, running up to 12 meters, and opening a door.

No matter what, the player can only perform one significant action per round. One exception is that players can always defend against two mental actions. Interestingly, players are subject to a limited number of actions against them in turn: two mental actions and two physical actions. Alas, if you’re getting shot at, you are subject to an unlimited number of ranged attacks.

What a player says they are doing, they succeed at, but defending actions are prioritized over attacking. Thus, if a character defends against an attack, they successfully do so. This does cost them both their significant action and 1 AP, which means they cannot defend more.

Throughout the book, a few Game Master Critical Concepts are scattered. These little notes highlight certain recommendations or approaches to the game. One of the interesting ones is that players should not be able to consult with each other if they are going to act or not in the First Phase. Additionally, they are given 5 seconds to decide if they will. After that, they have 5 seconds to say what they are going to do. If not, they lose out on the phase or action (the example text of play includes this). This is a smart concept to add. Because this is a diceless game with no random “generator” at all, the forcing into quick thinking and action helps to create tension and excitement along with the benefit of keeping a combat scene moving.

Outside of combat, many tasks are opposed (interrogating a person, for example). In this case, the player determines they want to spend 1 AP. The GM decides that person being interrogated wants to resist and spends 1 AP to do so. Deadlock. The player can then decide to continue — spending another AP if so. The GM then decides if they want to continue resisting. The play goes on like this until someone decides not to spend the AP or runs out of AP (in which case, they are unconscious).

The game also includes rules for skill chains, repeating skills, and extended skills. These are variations on a singular skill, 1 AP cost use. Chains means that multiple skills are necessary to complete a task. Repeating means the player must spend 1 AP on a regular interval to keep doing the action. Extended are for when using a skill means that the player does not have to repeat the 1 AP cost.

The player has 34 skills to choose from when creating characters. The list will be recognizable and largely familiar to RPG players.

Some advanced, optional rules allow the GM to tweak the experience of the game by allowing the GM to determine how much AP is necessary to successfully complete the task — in essence a difficulty level. However, this is not known the player, who must state what they think it costs. If the player gives an AP that matches or exceeds the GM’s value, the player succeeds at the task. Regardless, the player spends the AP. This also applies to combat. Here, the defender (whether the player or a GM’s NPC) determine how much they want to spend to defend an attack, which is kept secret. The attacker then declares how much they will spend. If the attacker spends more AP than the defender, the attack hits.

AP also functions as a sort of hit point or damage calculator. Successful attacks reduce your AP by set amounts depending on the weapon and type of attack. Exposed to the hard vacuum of space? Lose 5 AP per round. Sleep deprived? Lose 5 AP for every day you have not slept. Hit with a knife? Lose 5 AP. A phase pistol deals 10 AP of damage. Armor will absorb all of the damage from the first or second attack on the person (depending on the quality) but that’s it.

Fortunately, you can regain AP by resting, medical assistance and so on.

This all begs the question, how much AP does characters have? All characters begin games with 20 AP. This can increase as you play. At the end of every adventure, the player gets 1 Reputation Point. Players start at Reputation 1. Each Reputation level costs a set number of Reputation Points and brings with it benefits (like 5 additional AP, additional skill level, etc.).

Character creation is straightforward. Pick one of the eight species, which gives you a skill. Then you go through a process of choosing a background, education, career before being a bounty hunter, and why you became a bounty hunter. Each of these choices provides a specific skill. Note that skills levels are not needed. You either possess the skill or you do not.

You then choose an ability. This is a feat or talent that provides a bonus of some sort. For example, the Die Hard ability lets a character who reaches 0 AP to regain 5 AP once per day. Others provide more damage (usually once per scene), night vision, and so on.

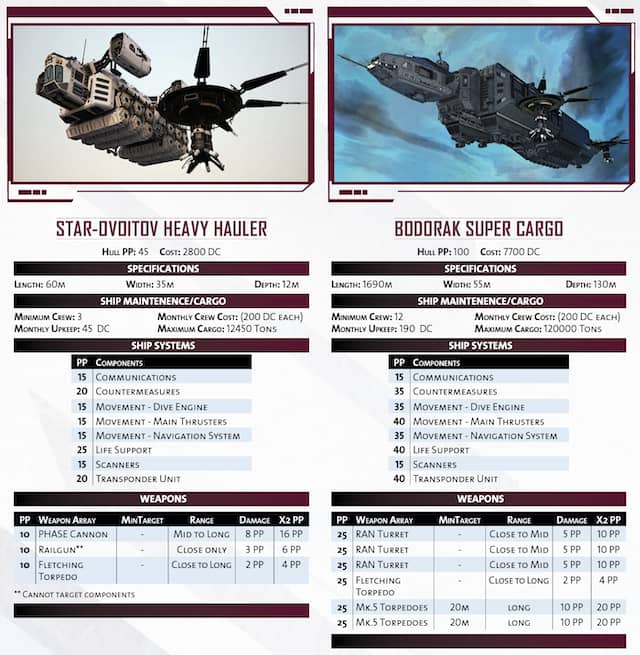

The game treats starships with relative ease. Combat and piloting them are no different than regular combat or completing other tasks. Ships have a Power Pool (PP), which are the analogue to AP. While using AP to pilot, shoot the guns, etc., still applies, PP factors in on damage done to the ship, how the individual components (like scanners, life support, etc.) function, and so on. The size of the ship determines how much PP it has, which is then allocated to the components that ship has. These can be shifted around using some skills, which improves the effectiveness of the component.

The core rules also provide a number of enemies and monsters the characters will encounter, but given the dice-less nature of the game, what is most important are the number of APs that enemy has. This can then be dialed up or down depending on the threat level of the enemy. In other words, it is very easy to re-skin these enemies for different enemies or create a quick one on the fly.

My omnibus addition of the game includes setting information that goes into a bit more detail about the specific species, the technology, and the Huntari Region of space. A number of factions and star systems are fleshed out. The book ends with a short introductory adventure.

This is a straightforward game to play and craft stories in. For those looking for a quick and easy system to play in along with a good starter setting, Bounty Hunter may be the game for you. The question that I have wrestled with the entire time is: Do I like the diceless system?

First, I think the approach taken here works from a mechanics standpoint. The players are entrusted with full control over their characters, their actions, and how the choose to spend action points. The game even injects methods for ensure tension in the decisions (you have five seconds to decide).

Second, while nearly every RPG contains an element of resource management, Bounty Hunter is only about resource management (if we’re talking only mechanics here). Yes, in Twilight: 2000, managing your ammo, fuel, and food is necessary to get the full experience. In Free League’s upcoming rule set, players also need to manage the number of actions they perform; however, this feels very much like a traditional game.

Third, I like the random element of the dice, and eliminating that random component was a design decision in making Bounty Hunter. Yes, players will make bad die rolls and fail when they probably should have succeeded, but I think that creates opportunities for interesting story telling that comes from outside the players or GM’s minds. We have to frame the story around those random results. Frankly, some of my best memories playing RPGs are when the players take a gamble or are in a tight spot and collect their dice, shake them in their hands, and roll them.

That said, with the back and forth between AP usage with the GM, Bounty Hunter is not just sit around and tell a story together. The players need to think about their actions, what it is important to spend them on, and keep back a few — perhaps — for taking some damage. I’m just not sure I can generate those thrilling moments where the outcome rests on a few dice.

The end result: I do not think Bounty Hunter is for me, but it may appeal to others. And that’s okay.

You can get a copy of Bounty Hunter here.

Patrick Kanouse encountered Traveller and Star Frontiers in the early 1980s, which he then subjected his brother to many games of. Outside of RPGs, he is a fiction writer, avid tabletop roleplaying game master, and new convert to war gaming. His last post for Black Gate was Co-Op Adventuring in Dungeons & Dragons. You can follow him and his brother at Two Brothers Gaming as they play any number of RPGs. Twitter: @twobrothersgam8. Facebook: Two Brothers Gaming.

I have not done much diceless roleplaying. I played Amber Diceless and I played and ran Everway, which includes randomization (the Fortune Deck) but differentiates its ranks strongly (each +1 in an Element means 2x the ability) so that it does not involve randomization to determine winner/loser (save for ties). I tend to agree with you, Mr. Kanouse, that I prefer to have the dice/cards add some “spice” to the mix, but I also confess that I am so familiar with that style of mechanics that I could just be biased. Please let us know if you hear how well Bounty Hunter makes out when it gets to the tabletops of more gamers.

Will do! I like the random element of dice….or even cards.