Fantasia 2020, Part XXX: Undergods

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

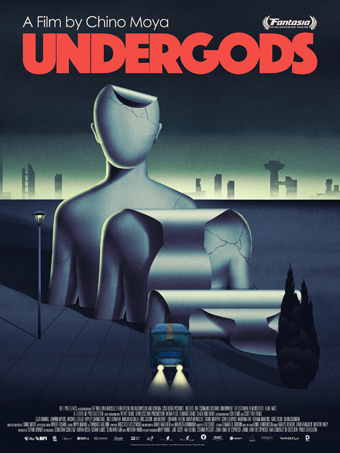

This year’s Fantasia Festival had a film in that tradition called Undergods. Written and directed by Spaniard Chino Moya, it’s officially a co-production from Estonia, Sweden, Belgium, and the UK. A series of interlaced stories told by a couple of bored men on a long journey by truck, it openly refers to the work of E.T.A. Hoffmann, one of the early masters of the kind of fiction I described above. That made Undergods the second Hoffmann-influenced film I saw at Fantasia after Tezuka’s Barbara, which was inspired by the tales of Hoffmann at several removes. Hoffmann was a writer who played about with doubles and alter-egos — one of his unfinished novels, Kater Murr, imagined the autobiography of a complacent bourgeouis housecat written on the back of letters by a frenzied Romantic composer — so it’s interesting to note that Barbara evoked the content of Hoffmann’s stories without their complexity of form, while Undergods had the form of stories commenting on stories without much of the fantastic content.

The film opens with the truckers (Johann Myers and Géza Röhrig), gathering corpses in a ruined city. They start talking about their dreams, which leads to them telling three stories. In the first, an older man (Michael Gould) and his wife (Hayley Carmichael) take in another man (Ned Dennehy) who claims to be a tenant in their building who’s locked himself out of hs room; he’s helpful, but doesn’t leave, and soon appears to be manipulating them for some unknown reason. From there we pass to a father telling his young daughter about the aftermath of those events, and then launching into a bedtime story. That story’s about an old and wealthy businessman (Eric Godon) who betrays a brilliant but naive architect (Jan Bijvoet); in revenge the architect kidnaps the businessman’s daughter (Tanya Reynolds), leading the businessman to team up with her boyfriend to try to find her — eventually ending up in the city of the corpse-gatherers. The last story begins where the last ended, with a prison in the ruined city, where an inmate (Sam Louwyck) is released to return to his family in a modern city in the developed world; Sam’s wife (Kate Dickie), thinking him dead, has long since married Dominic (Adrian Rawlins) whose perspective we follow as the family tries to adapt to Sam’s reappearance.

That’s a lot of plot. But the stories, intricately connected as they are, gain little in the telling. The actors are fine, the cinematography’s solid with gusts to excellent (particularly in the images of the ruined city), and the visual storytelling’s effective. But the writing never catches fire. The characters aren’t especially vivid, for all the efforts of the actors, and the individual plots end up disappointing. There’s some tension in the businessman’s search for his daughter, but the development’s random. The mysterious tenant’s manipulation of the elderly couple is random. And Dominic’s adjustment to Sam’s return is incongruous without feeling Kafkaesque, overlong and unfunny (despite the best efforts of Rawlins).

That’s a lot of plot. But the stories, intricately connected as they are, gain little in the telling. The actors are fine, the cinematography’s solid with gusts to excellent (particularly in the images of the ruined city), and the visual storytelling’s effective. But the writing never catches fire. The characters aren’t especially vivid, for all the efforts of the actors, and the individual plots end up disappointing. There’s some tension in the businessman’s search for his daughter, but the development’s random. The mysterious tenant’s manipulation of the elderly couple is random. And Dominic’s adjustment to Sam’s return is incongruous without feeling Kafkaesque, overlong and unfunny (despite the best efforts of Rawlins).

The frame story’s intriguing, and there’s potentially something fascinating in the way that the corpse-collectors in the science-fictional world tell stories about our world. Modern developed society becomes the setting for the dreams of people living among ruins, for wonder-tales and impossible things. The points of connection between the two worlds is also well-handled; you get the sense of the ruined world as the substructure of this one. Sam and the labourers in his prison perhaps represent the workers in poorer countries who make the goods the rich countries consume; his inability to talk about his experience could be a way of demonstrating how the rich world does not want to hear of the experiences of others.

But this way of thinking leads to what I have to consider a failing in the film. I want to stress that viewed purely on its own terms I thought Undergods was an interesting misfire; and I stress that because in illustrating why it misfired I’m going to cheat as a critic, and cite the director’s own thoughts about what he was trying to do with his film. For Moya, the film’s about the collapse of “civilisation built by the white male,” who “fear ‘the Other’: an abstract entity that represents everyone that is not themselves and that has come to steal their jobs, their houses, their wives, daughters, sons and ultimately their countries.” This is a perfectly reasonable theme, but it doesn’t come across very well, at least in part because most of the characters representing Otherness are also white men. That is: they’re others as individuals, but not Others in the sense of being members of groups visually distinct from the white men Moya’s trying to critique.

But this way of thinking leads to what I have to consider a failing in the film. I want to stress that viewed purely on its own terms I thought Undergods was an interesting misfire; and I stress that because in illustrating why it misfired I’m going to cheat as a critic, and cite the director’s own thoughts about what he was trying to do with his film. For Moya, the film’s about the collapse of “civilisation built by the white male,” who “fear ‘the Other’: an abstract entity that represents everyone that is not themselves and that has come to steal their jobs, their houses, their wives, daughters, sons and ultimately their countries.” This is a perfectly reasonable theme, but it doesn’t come across very well, at least in part because most of the characters representing Otherness are also white men. That is: they’re others as individuals, but not Others in the sense of being members of groups visually distinct from the white men Moya’s trying to critique.

The architect who kidnaps the merchant’s daughter is a foreigner. But then he also takes out his vengeance on someone who didn’t wrong him, so not a great image of an alternative kind of mentality. For that matter, the mysterious tenant of the first story is also someone who comes in to the life of an everyday couple and disrupts it in disturbing ways. Sam does not end up being a positive factor in his old family’s life, either. You could make that work; you could illustrate the everyday lives of the couple in the first story being part of a system that exploits others. You could emphasise the merchant’s exploitation of the architect and also give the merchant’s daughter more of a voice in the story. You could talk about the brutality of civilisation fostering brutality in marginalised others. But that doesn’t happen, and the film’s exploration of otherness generally fails to register.

It is in fact far closer to the Hoffmannesque theme of the doppelganger — an Other who is not foreign, but who is clearly linked to oneself. But nothing much comes of this theme. I can’t see how the film works thematically even given what Moya wanted to do with it. There is definitely a sense of things running down, and of the cruelty underlying the everyday capitalist world. But the stories don’t illustrate or develop this theme in any compelling way. Undergods has some interesting aspects, but remains a clever work of form in search of content.

It is in fact far closer to the Hoffmannesque theme of the doppelganger — an Other who is not foreign, but who is clearly linked to oneself. But nothing much comes of this theme. I can’t see how the film works thematically even given what Moya wanted to do with it. There is definitely a sense of things running down, and of the cruelty underlying the everyday capitalist world. But the stories don’t illustrate or develop this theme in any compelling way. Undergods has some interesting aspects, but remains a clever work of form in search of content.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.