Fantasia 2019, Day 6, Part 1: Ad Astra Book Launch, and Nao Yoshigai x 4: Of Blooming Flowers and Dead Skin

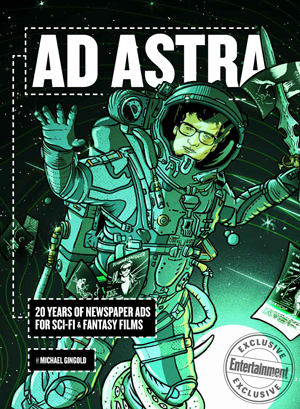

On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films.

On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films.

Gingold, a former editor-in-chief of Fangoria, said he’d collected ads since he was 12 years old, and the book thus covered films from the original Star Wars through to A Phantom Menace. He showed some of the images included in the book while discussing trends in newspaper ads — and in movies, noting that science fiction began to perform reliably at the box office in these years with Moonraker the most popular James Bond film up to the time of its release in 1979, while in the summer of 1980 The Empire Strikes Back and Friday the 13th were the only real financial successes. Gingold went on to say he had a sympathy for smaller films, such as Mighty Peking Man, a Shaw Brothers movie first released in North America as Goliathon.

He observed that while we debate ‘special editions’ of films today, the idea perhaps began with the 1980 version of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Among the ads he showed was the one for Dune packed with expository text; and variant ads for films like Excalibur and Flash Gordon. Some films had seasonal ads, as Superman II did for July 4 or ET for Christmas. On the other hand, other films (like Howard the Duck) had to change their ads in an attempt to rebrand the film. Review ads began to emerge (prompting an ad for Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure that mocked the format), as did ads featuring tag lines or actor’s name — a whole sub-genre of ads for Arnold Schwarzenegger movies placed the name “Schwarzenegger” in all-caps at the top of the ad. Gingold also noted that he included in the book some of his favourite quotes from his favourite dyspeptic movie critic Rex Reed; such as, for example, Reed’s line that The NeverEnding Story was “worse than girl scout cookies.”

From the book launch in Concordia’s York Amphitheatre I crossed the street to the De Sève Theatre. There, I watched a program of short films by experimental director Nao Yoshigai. Yoshigai’s a dancer and choreographer as well as filmmaker, and her work has already met with considerable acclaim; her piece “Grand Bouquet” was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes. Fantasia’s program, Nao Yoshigai x 4: Of Blooming Flowers and Dead Skin gathered four of her shorts together, culminating with “Grand Bouquet.”

The first short was “Stories Floating on the Wind,” a nine-minute film centred on a young woman (Ema Maeda) bicycling around a coastal Japanese town. She encounters wildlife and strange children; the soundtrack emphasises the rush of wind, and the lighting brings out the startling brightness of the colours she sees. There’s a densely realist feeling to the film even as the richness of the sensory experience moves it beyond realism, and some of the puzzling things she sees imply something else going on. I thought the movie was a strong experience, but I struggled to find a story in it.

The first short was “Stories Floating on the Wind,” a nine-minute film centred on a young woman (Ema Maeda) bicycling around a coastal Japanese town. She encounters wildlife and strange children; the soundtrack emphasises the rush of wind, and the lighting brings out the startling brightness of the colours she sees. There’s a densely realist feeling to the film even as the richness of the sensory experience moves it beyond realism, and some of the puzzling things she sees imply something else going on. I thought the movie was a strong experience, but I struggled to find a story in it.

“The Pear and the Fang” was next, a thirty-minute tale co-written by Yoshigai with Tomoyuki Takahashi about a recluse named Ayano and a pear farmer named Satoko. Satoko finds one of her pears missing and a bloody fang beside it. Ayano finds a pear in her apartment and a tooth missing. The connection seems obvious, but watching these two come together over the course of the film is engaging because the process is dreamlike and unpredictable, a lovely and engaging queer love story.

Ayano grows obsessed with pears, filling her apartment with round green fruit as she seeks the one with just the right flavour and just the right sound when she bites into it. Satoko struggles with her career in the orchards where she is falling behind other farmers. Both characters come across well, but although there is dialogue in this film and a clearer narrative than the other shorts the primary effect is still of a gentle surrealism. The sound and visuals are as meticulously designed as in the other films, but paradoxically because the dialogue lets us understand more about the characters we get more out of their body language and non-vocal communication.

The story’s simple on one level, but told well. It’s a deeply satisfying short, a kind of visual poem or stylised fable. The richness of the colours and soundscape give a strange dimension to the storytelling, emphasised by the quiet weirdness of the characters and the elliptical structure. It’s an unusual way to tell a tale, and it works.

The story’s simple on one level, but told well. It’s a deeply satisfying short, a kind of visual poem or stylised fable. The richness of the colours and soundscape give a strange dimension to the storytelling, emphasised by the quiet weirdness of the characters and the elliptical structure. It’s an unusual way to tell a tale, and it works.

The 37-minute “Hottamaru Days” followed. Set in a house in which a young woman (Risa Oda, I think; credit information is scanty) lives with four white-clad dancing spirits. They draw closer to her, and gather up her shed hair and flakes of skin like relics. But there is danger to her in how close they come.

This film left me baffled. There is no dialogue I can recall, and meaning is expressed through dance, an artform to which I am not sensitive in the least. It is pleasant to look at in its colour choices and angles. But I found it uninvolving and slow as I tried to understand what was happening and why I should care. Notwithstanding that bafflement, the film was relatively engaging, and I suspect this has to be considered a successful movie for which I am simply the opposite of the ideal audience. The music is interesting, the rhythm and dance have a kinetic unpredictability, and the house has a sense of place and character; if I understood what I was watching or had any emotional reaction to it, I’d probably like the film quite a bit.

The 14-minute “Grand Bouquet” was last (its Japanese title, which I could not find, apparently directly translates as “For You, Who Are Now The Most Beautiful”). It’s a simple enough structure: a woman (Hanna Chan) sits in a white space and is confronted by a mass of darkness. The darkness challenges her, and she tries to answer, but only vomits flowers. The darkness assaults her, and she continues to try to respond.

The 14-minute “Grand Bouquet” was last (its Japanese title, which I could not find, apparently directly translates as “For You, Who Are Now The Most Beautiful”). It’s a simple enough structure: a woman (Hanna Chan) sits in a white space and is confronted by a mass of darkness. The darkness challenges her, and she tries to answer, but only vomits flowers. The darkness assaults her, and she continues to try to respond.

There is a weird violence in this film, and striking imagery. The flowers are bright and oddly slick; the blackness and the whiteness of the monster and of the background give a striking contrast. Chan effectively gets her character across through motion and expression. It’s another movie in which it’s hard to see exactly what’s going on, but in this case I felt it didn’t matter. The conflict had a kind of archetypal feel that made it work. There is a director’s statement that makes a direct connection between the story of the film and the MeToo movement, though not necessarily in an obvious or simplistic way; Yoshigai writes about the movie as representing her voice, and it strikes me as powerfully ironic that in the movie the woman struggles to speak but cannot.

Over the course of the four movies I saw some common elements. First, most obvious, the films are built on physicality and motion. Yoshigai’s background in dance is clear and informs not only the blocking of the actors but also perhaps the rhythms of the editing. Second, colour and sound are important, worked out meticulously, presenting a kind of sensory lushness that’s always engaging. Third, on the level of story and theme, women, women’s experiences, and women’s loves and struggles are the subjects. Fourth and finally, the narratives are relatively basic and tend to work depending on whether they resonate as myth with the viewer. These are strong formal exercises in film, but to my mind their power as stories are not always enhanced by the particular approach to form they use. If you are interested in film purely as film, or have a more direct connection to the stories than I do, this may not be a problem.

After the movies, Nao Yoshigai and actress Hanna Chan (“Grand Bouquet”) came out to take questions. (As usual, what follows comes from hand-scribbled notes.) Asked first how she got into film from a dance background, Yoshigai said that she made “Hottamaru Days” at university, inspired by the idea of a woman dancing in a bath, and wanting to make a movie based on a dance. Asked how she approached sound and sound design, Yoshigai spoke of sound as equivalent to words, and how sounds tell her stories and how as a result she thinks about sound carefully. She also observed that Ayano (“The Pear and the Fang”) is her, while Satako is the other side of her.

After the movies, Nao Yoshigai and actress Hanna Chan (“Grand Bouquet”) came out to take questions. (As usual, what follows comes from hand-scribbled notes.) Asked first how she got into film from a dance background, Yoshigai said that she made “Hottamaru Days” at university, inspired by the idea of a woman dancing in a bath, and wanting to make a movie based on a dance. Asked how she approached sound and sound design, Yoshigai spoke of sound as equivalent to words, and how sounds tell her stories and how as a result she thinks about sound carefully. She also observed that Ayano (“The Pear and the Fang”) is her, while Satako is the other side of her.

She was asked about the title “Hottamaru Days,” and she said she made the word herself as a portmanteau of “hotteoku,” to leave something as it is, and “tamaru,” something that accumulates. She spoke about how that had to do with the bits of the body that drop from the human form, pieces of protein, and how that contrasted with the quest for love.

Asked about the process of making “Grand Bouquet,” Yoshigai said she wrote the script two years ago, but thought she would need a large budget to make it; she had never worked with CGI at that time. She was, however, lucky, and a moment came when she had the chance to make it, and the budget was not as much as she’d feared. She looked for sympathetic people willing to collaborate with her, and found her actress on Instagram. Chan said it was her first time collaborating with a Japanese director, and also her first time seeing Yoshigai’s work, which she compared to seeing her brain on screen; Chan said she liked seeing how Yoshigai thinks about movies. Chan was asked how difficult it was for her to play the movie with no dialogue, and she said it was quite difficult, as she wanted in-character to speak. She had to drop to the floor a lot, and imagine the blackness hitting her and talking to her, so the process was like an action film for her.

Asked about the process of making “Grand Bouquet,” Yoshigai said she wrote the script two years ago, but thought she would need a large budget to make it; she had never worked with CGI at that time. She was, however, lucky, and a moment came when she had the chance to make it, and the budget was not as much as she’d feared. She looked for sympathetic people willing to collaborate with her, and found her actress on Instagram. Chan said it was her first time collaborating with a Japanese director, and also her first time seeing Yoshigai’s work, which she compared to seeing her brain on screen; Chan said she liked seeing how Yoshigai thinks about movies. Chan was asked how difficult it was for her to play the movie with no dialogue, and she said it was quite difficult, as she wanted in-character to speak. She had to drop to the floor a lot, and imagine the blackness hitting her and talking to her, so the process was like an action film for her.

Yoshigai was then asked if she tried to engage the senses beyond sight in her cinema, trying to film the invisible; according to my notes, she said through the translator “You see invisible things in my film? Thank you so much.” She said that there are many invisible things in the world, that cannot be recognised by human beings; she wants to make a movie not only for human beings. Asked about the locations in her movies and their influence in the films, she said that “Hottamaru Days” was a house story, so important to get right; the longer one lives in a house the more of a person will be attached to things there, and something of the person will be visible in the layout of furniture as things will be placed where they can be used easily. Thus the house is an extension of the body. She had to look hard to find the right house but finally did, a place that is a studio now but was a lived-in house only 10 years before. She tried to shoot without moving furniture or furnishings, and allow them to provide ideas. She felt it was important to shoot things as they were, to shoot reality, and allow reality to meld with the things as they were in her mind.

Yoshigai was then asked if she tried to engage the senses beyond sight in her cinema, trying to film the invisible; according to my notes, she said through the translator “You see invisible things in my film? Thank you so much.” She said that there are many invisible things in the world, that cannot be recognised by human beings; she wants to make a movie not only for human beings. Asked about the locations in her movies and their influence in the films, she said that “Hottamaru Days” was a house story, so important to get right; the longer one lives in a house the more of a person will be attached to things there, and something of the person will be visible in the layout of furniture as things will be placed where they can be used easily. Thus the house is an extension of the body. She had to look hard to find the right house but finally did, a place that is a studio now but was a lived-in house only 10 years before. She tried to shoot without moving furniture or furnishings, and allow them to provide ideas. She felt it was important to shoot things as they were, to shoot reality, and allow reality to meld with the things as they were in her mind.

That ended the questions, but I still had another film to see that night — a documentary, and one that would be followed by an unexpected surprise.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.