Review: Spooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the Past by Jeb J Card.

Funny story about Mayan gifs glyphs.

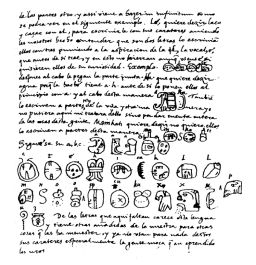

Before the 1860s, Mayan glyphs were an untranslated Rorschach Test for those who wanted to find lost worlds — spiritual or physical — in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica: “Weird swirly writing style, therefore Egyptians from Atlantis who understood the Secrets of the Universe.”

Then Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg discovered a 16th-century document in a Spanish archive. It seems Spanish government officials were presumed corrupt until proven otherwise, so had to lodge a defence of their actions in office. For some reason, Diego de Landa, Archbishop of Yucatan included a bilingual alphabet in his.

The Mayan Rossetta Stone!

Brasseur rushed off to translate the Madrid Codex — a compilation of Mayan writings that had somehow survived the bonfires of the Inquisition.

Unfortunately, he didn’t realise that the Archbishop had monumentally screwed up, presumably because he was doing the Western thing of TALKING VERY LOUDLY TO THE NATIVES.

So when he said, “How do you write H?” he got back the Mayan for glyphs for… yes, you’ve guessed it, “Ah-che”. We can guess that “K” would have come back as “K-Ay” and so on. This just like in Terry Pratchett’s The Color of Magic where the places are all called things like “Big Tree” and “Your Finger You Fool,” and in Bonny Scotland where the government maps have a superfluity of “Black Lakes.”

De Brasseur heroically wrung a translation out of the Codex and was delighted to find evidence for the fiery destruction of Atlantis and the diffusion of high culture to the Americas from the West: this was a scholar whose mindscape was populated by Phoenicians in Brazil, Mayas at the Temple of Solomon, hidden meanings in colonial documents, and establishment conspiracies to cover up the quality (!) of pre-Hispanic craftsmanship.

Erk.

It wasn’t until about a century later that a Russian academic realised the Archbishop’s error, but he was a Russian and it was the Cold War, so it took two decades before anybody took him seriously.

I’m telling you this in part because it’s both cool and funny, but mainly because it illustrates some of the main themes of Spooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the Past, an academic book by Dr Jebb J Card, host of the Archaeological Fantasies podcast (entertaining listening in these stressful times).

The book isn’t about Mayans. Rather, it’s a pretty definitive history of alternative archaeology and its context, covering not just intellectual history, but social, cultural and political. It throws light — some of it harsh — on the tropes we love in our fiction. It even has something to say about HP Lovecraft…

This is very much an academic text. Approachable, but it helps if you have a rough idea of the historical context and are comfortable with words like syncretic. It starts off in a slightly formal tone — perhaps on the assumption that some academics will only read that far — but thankfully slides towards the chatty, with humorous asides and subtitles like “Closing the Barn Doors after That One Weird Horse Got the Hint and Left.”

Granted that it’s an academic text and well written, I still have a few niggles. Dr Card could have supplied us with more signposting, tying anecdote to overall argument. Characters and institutions sometimes reappear after a hiatus, but with no tagging to remind us who they are. The index makes up for this, but it would have been better to have clauses like “who we last met looking for Atlantis in the Azores” and “the same institution we saw purchasing mummies on the black market.” This would have made it easier to follow the passages of sometimes labyrinthine institutional history, which — though illuminating from a gaming or fictioneering source material point-of-view — didn’t always feel tied to the main theme.

Even so, this a highly readable book that Stephen Pinker would approve of. I’m guessing it supports a course Dr Card teaches, which explains the price. For your money, you get a robustly bound hardback, 274 pages of well written-text and illustrations followed by footnotes and a detailed bibliography. It’s pretty much the last book on Alternative Archaeology you’ll “need” to buy, which is what you’re really paying for. (Me, being a penniless minor author, I blagged a review copy.)

By “Spooky Archaeology,” Dr Card means the ideas and practices that we now think of as “Alternative Archaeology,” but which were not always “Alternative.” In other words the stuff of Indiana Jones and HP Lovecraft. You can therefore treat the book as a catalogue of cool ideas that failed to swim upstream far enough to make the evidence-based spawning grounds.

The sweeping and lively narrative covers: ancient archaeology and restorations — both Egyptians and Mayans investigated and restored their heritage; magic and tomb robbing, ancient and modern — did you know some modern Egyptian tomb robbers still use magical protection?; occult and psychic archaeology, antiquarianism, mummies and curses — including the original Egyptian story of a mummy that went walkabout; crystal skulls — all fake; lost continents – Atlantis and Mu; colonialism and diffusionism; haunted places and artifacts; real-life Indiana Jones figures; archaeologists who were spies; Theosophy and modern occultism — Dion Fortune, Aliester Crowley; witchcraft; modern ritual murder; ancient aliens; and HP Lovecraft in context.

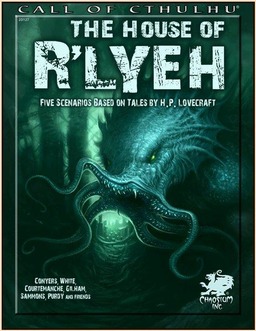

This breadth makes for an amazing read, but is a challenge to review in detail. Suffice it to say that you could mine this for, say, Call of Cthulhu and not run out of inspiration for a long time.

However, Spooky Archaeology is more than just a cabinet of curiosities. It also explains how those curiosities work culturally, and where they came from. In some ways it’s a Social History of Archaeology.

Let’s go back to the comedy of the Mayan gifs glyphs (which occupies just a couple of pages of the text) and unpack the story from Dr Card’s perspective. (A slightly terrifying exercise — when I summarise academic books I half expect the author to pop up and give me a mark out of 30, and later I get nightmares about sitting final exams.)

Until Archaeology fully professionalised after WWII, Spooky Archaeology was — mostly — mainstream. Serious scholars entertained the possibility of lost continents, or lost Egyptians planting civilizations, and investigators deployed dowsing and conjured witch cults up from tenuous textual evidence. Professionalisation didn’t however destroy Spooky Archaeology because an increasingly educated population felt snubbed by the gatekeepers who dared to demand detailed evidence and chains of reasoning, and they preferred their version of history anyway: the poorly understood past is the playground for the imagination.

It all looks awfully like LikeWar‘s, Fake News: novel, simple, and resonant.

It’s novel because it contradicts the mainstream historical narrative: “A Scholar looked at Lost Cities on both sides of the Atlantic. What He Discovered will SHOCK you to the core…”

It’s simple because it collapses the complexities of history into “proto-history,” so that Medieval Mayan pyramids and Ancient Egyptian pyramids coexist, and then offers simply explanations for complex phenomena, here explaining the parallel rise of civilizations in terms of cultural transfer from Old World to New, or Lost Continent to both.

It’s resonant because… well, what’s not to like about a secret history of tragic lost civilisations and intrepid explorers who know the secrets of the universe? And for less comfortable reasons…

Which brings us to Politics and Colonialism.

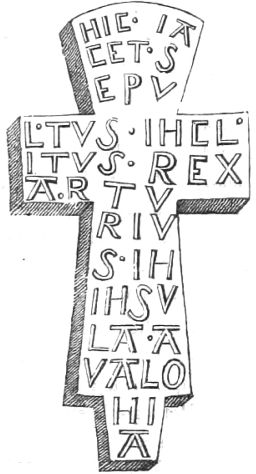

Archaeology has always been political. King Henry I had “King Arthur” dug up in order to establish that he wasn’t coming back to kick out the Normans, and at the same time to align his dynasty with British mythology. Napoleon III turned Alesia into a national shrine in order to take refuge in nationalism. And at times archaeologists were also agents, “just happening” to investigate in sensitive areas — this explains some otherwise eccentric expeditions going after the Ark or the Yeti — or accepting funding in return for keeping an eye out for enemy bases.

Where Colonialism is involved — as here with the Mayan glyphs — certain tropes keep popping up (the names here are my own):

Two related tropes seem to reflect a suppressed sense of guilt: “Cursed Tomb/Artefact” and “Haunted Burial Ground”. Paging Lady MacBeth…

The remaining tropes seem designed — perhaps evolved? — to make the coloniser feel better about doing the colonising. “We Understand Your Illuminated Ancestors Better Than You Do” projects mystical fantasies onto the pre-colonial generations, and therefore spins the coloniser as their true spiritual successor, and the “natives” as having fallen from grace, so deserving subjugation. “A Lost White Tribe Built Ur Monuments, Therefore Colonialism” is even worse because it makes the colonisers into the actual heirs, and the indigenous people into mere lately-come squatters. (We see this in the Mound Builders “controversy”.) The “Aliens Did It” variation is only slightly better, but still erases local achievements and connections.

This is not polemic. Dr Card isn’t trying to guilt trip us over our love of Lost Tribes and Sunken Continents, he’s just putting Spooky Archaeology in the context of its cultural history.

It does, however, have some interesting implications for us and the things we like.

First, it helps us better understand the Pulp Era fiction we gleefully consume, what assumptions and obsessions drove scholars and explorers, what ideas were taken for granted. Perhaps it illuminates HP Lovecraft’s dark humor: “Alien Space Slugs Built Your Monuments AND Your Species, Therefore Doom and Nihilism.” It certainly makes it easier to portray or even create Lovecraftian characters.

Second, it suggests that some tropes have second-order effects that most of us find distasteful. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying a yarn that’s “of its time,” but we probably don’t need any new secret origin stories, unless they’re set in space.

The conclusion for Dr Card is that Spooky Archaeology isn’t going to go away any time soon. It has its roots the profession’s past, and spookiness is spawned by the very nature of the exercise — you can’t rummage around in the mythical without getting some myth stuck to your boots. Archaeologists should stop shrugging off the fake news and engage in the public discourse. If it were slightly fluffier and less expensive, Spooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the Past would be a direct contribution to that effort.

However, as it stands it’s a must have for the thinking tabletop gamer, reader or writer whose imagination stretches to the ancient and the mysterious. As I said, this is probably the last book you’ll need to buy on the subject of Alternative Archaeology.

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of The Wreck of the Marissa (Book 1 of the Eternal Dome of the Unknowable Series), an old-school space adventure yarn about a retired mercenary-turned-archaeologist dealing with “local difficulties” as he pursues his quest across the galaxy. His other titles include Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”) and Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

“you could mine this for, say, Call of Cthulhu and not run out of inspiration for a long time.”

Say no more, Bwana!

Fascinating stuff as usual, Harold. I remember that Celtic epic, ‘The Tain’ (ie, ‘The Raid’) as being regarded as a window into Iron Age culture until it transpired it was written in the 8th century by some monk, who seems to have borrowed liberally from a variety of sources, and who wrote it for political reasons.

Your Illuminated Ancestors. Post-colonial cultures may bear some of the culpability, too. There was a push to promote ‘The Celts’ as a distinct race during the early days of Irish independence. Are Heavy Metal fans a distinct race? Who knows? Maybe, I guess.

it’s interesting how one piece of evidence can be open to multiple interpretations. For example, the idea that the Celts decorated their homes with the heads of their enemies is now under question – the heads more likely being those of comrades who’d fallen in battle.

We loved the Tain in highschool – Kinsella translation got passed around as the source for 2000AD’s Slain. Not surprised that it is something of an Ossian.

There is a plausible theory that Asser’s Life of Alfred is also a forgery: wrong style of writing, most of it drawn from the Anglo Saxon Chronicle – probably created as an elaborate way to validate a monastery’s land rights.

Authenticity defended fiercely by scholars who built their careers on the book, who in turn set about debunking the magnum opus of the scholar who cried forgery. Tit for tat! Academic fake news!

The Kinsella version is great. I still get 2000Ad every week and the current edition has a Slaine story in it.

Looks like King Arthur’s historicity is also under scrutiny –

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/dec/13/king-arthur-by-nicholas-j-higham-review

Seem to be a lot of scribes/monks/clerks in the middle-ages with time on their hands!

King Arthur fictional? OMG! I’m shocked.

But actually there’s so little textual evidence, it’s impossible to say for certain either way: I mean, a couple of entries in the Easter Annals which could be interpolations, a throw away reference in Gododin – “He glutted ravens on the battlements, though he was not Arthur” – some terse entries in Nennius. Plus it’s not clear whether Arthur *was* Arthur, and not an alternative name for Ambrosius or even, so help me god, Magnus Maximus.

However, the idea of a dynasty of warlords running the army, while the cities and provinces devolve, is a plausible one since it is so similar to what happened in Gaul…