A Demanding Work that Sings all the Stronger in 2018: The Queen of Air and Darkness by T.H. White

|

|

In my early teens, I discovered and devoured T.H. White’s omnibus quartet of novels, The Once and Future King. The first and most child-like remains the best known: The Sword in the Stone. After this, and unjustly neglected (by Disney and the world in general), come The Queen of Air and Darkness, The Ill-Made Knight, and The Candle In the Wind.

In my later teen years, I concluded that The Once and Future King, taken as a whole, was the single best novel I had ever read. Having reached the ripe old age of fifty, it’s time to re-evaluate. Is White’s work still worth its weight in gold?

Perhaps you recall Book One, in which the young King Arthur, known affectionately as the Wart, meets Merlyn, gambols through a lifetime’s worth of transformational adventures, and draws a certain sword from a stone. Hysterically funny, dreamy and given to long flights of fancy about hawks and birds, The Once and Future King still works genuine magic, even when its digressions and mood swings threaten to topple the whole everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink mess into a stew of narrative anarchy.

In short, it’s a full meal and then some, and I, along with fantasy lovers the world over, adore it still. (Ursula K. LeGuin, R.I.P., lent her opinion to one edition’s jacket copy, saying, “I have laughed at White’s great Arthurian novel and cried over it and loved it all my life.”) Yet, many seem unaware that the cycle, tracing Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, continues.

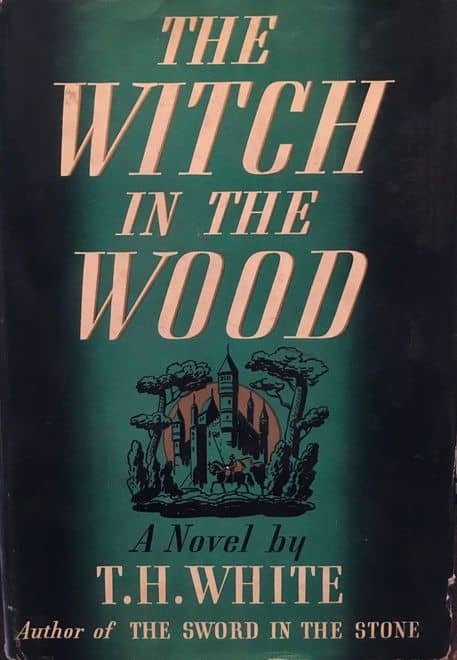

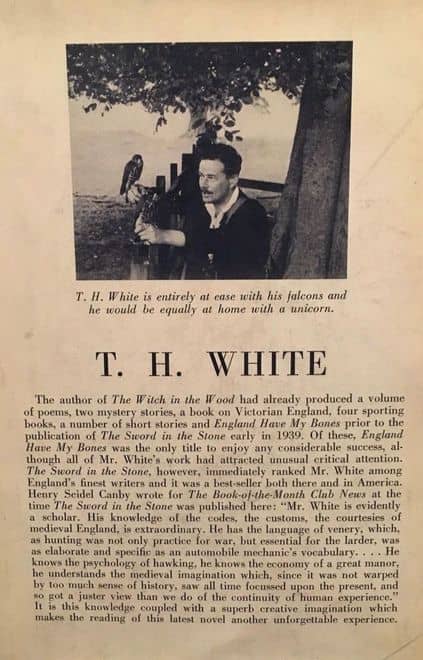

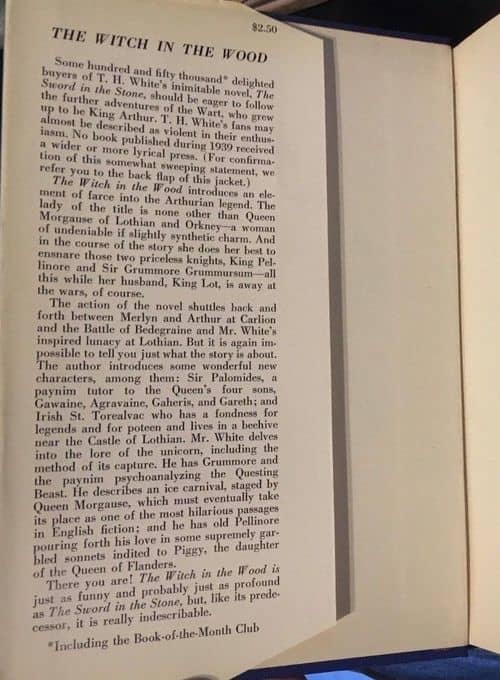

Book Two began life as The Witch in the Wood, and arrived in print in 1939, just as the world fell off a precipice it hadn’t seen coming, and descended into a darkness from which it is still fighting to recover. Revised and expanded, The Witch in the Wood became The Queen of Air and Darkness, and no book better upholds the argument for valuing a work as the sum of its discordant parts.

The queen referenced by the title is Morgause, Arthur’s half-sister, who in the book’s final moments seduces Arthur. The product of their union will be Mordred, the ultimate personification of human and personal doom.

The queen referenced by the title is Morgause, Arthur’s half-sister, who in the book’s final moments seduces Arthur. The product of their union will be Mordred, the ultimate personification of human and personal doom.

White only touches on the actual seduction; he understands that some pictures become most vivid when left unpainted. Indeed, Morgause herself hardly figures in the story, a tale that divides its time between three primary subjects: the funny but lethal Socratic arguments between Merlyn and Arthur; the growing pains of Morgause’s sullen, argumentative sons (Gawaine, Agravaine, Gaheris, and Gareth); and love, as illustrated by three bungling knights (Sirs Pellinore, Grummore, and Palomides) and their besotted quarry, the Questing Beast.

Clearly, White felt no need to discipline himself. One imagines he’d have thought poorly of most of our contemporary novels, with their honed, rigidly streamlined perfectionism. Whatever muse White happened upon, he set it down, allowing at all times for two guiding principles: to update and give relevance to Le Morte d’Arthur, and to work out to his own satisfaction the great debate between Might versus Right.

That this theme should so consume him in the wake of World War I and on the eve of World War II should come as no surprise. That this same task has occupied so few writers since is, to my mind, a far greater shock. It’s as if artists in the main, at least in my brief lifetime, have come to believe it gauche to bring up the perils of their forebears, and yet here we stand again, sabers rattling in all corners of the globe, and notions of American Exceptionalism (and interventionism) at the forefront of every possible foreign policy discussion.

That this theme should so consume him in the wake of World War I and on the eve of World War II should come as no surprise. That this same task has occupied so few writers since is, to my mind, a far greater shock. It’s as if artists in the main, at least in my brief lifetime, have come to believe it gauche to bring up the perils of their forebears, and yet here we stand again, sabers rattling in all corners of the globe, and notions of American Exceptionalism (and interventionism) at the forefront of every possible foreign policy discussion.

What White concludes is hardly controversial (at least on its face): Might must be made to serve Right, even if it must be hoodwinked and flattered into doing so. Thus, chivalry. Thus, the Round Table, where the bloodthirsty tendencies of Arthur’s various immature vassals may be channeled and given over to mythic, public celebration.

For White, notions of love as a higher goal and noble calling march hand in hand with chivalry. Nor is he miserly in his estimation of what love might encompass. Arthur’s love for Guenevere may serve as a certain gold standard, but a mother’s love for her children also receives its due (though in the case of Morgause, it must be measured by its absence), and so, too, must its opposite, a child’s need for love from a parent. Friendship itself is held to the light as a virtue, and as a most deserving brand of love. Sir Kay, a stubborn dullard at times, would do anything for Arthur, and he for Kay. The lengths Sirs Grummore, Palomides, and Pellinore would go for each other is beyond estimation.

Indeed, White’s reach on the subject of love is commendable: the Questing Beast falls in love first with a facsimile of itself, then with Sir Palomides who serves (according to White) as the Beast’s psychoanalyst, thereby transferring its affections onto himself. Do such anachronistic references belong in such a feudal tale? Absolutely, thanks to White’s hilarious conceit that Merlyn is busy living backwards. Does White thereby allow all sorts of twentieth century references to leap into this otherwise courtly narrative? He does, gleefully dispatching Hitler, higher mathematics, and Victorian fox-hunts, all the while dipping his linguistic quill into the antique delights of Chaucer and Mallory.

In the midst of all this comes a tragic, unforgettable encounter with a unicorn, to say nothing of a truly creepy aside (really the only moment given to Morgause on her own), during which the Queen of Air and Darkness boils a black cat, intending to discern which of its bones will turn her invisible. Her reaction to her own experiment seemed to me then and seems to me now to be one of the most incisive character studies ever committed to paper, one achieved in less than two pages.

creepy aside (really the only moment given to Morgause on her own), during which the Queen of Air and Darkness boils a black cat, intending to discern which of its bones will turn her invisible. Her reaction to her own experiment seemed to me then and seems to me now to be one of the most incisive character studies ever committed to paper, one achieved in less than two pages.

All in all, The Queen of Air and Darkness strikes me as a thorny, demanding work that sings all the stronger in 2018. It succeeds best in that it has me eager to continue on, to focus on Lancelot in The Ill-Made Knight, the first of the quartet to leave comedy behind in lieu of deep introspection, an inquiry into how vanity and ego may undo even the most valiant enterprise.

So. I go now to the depths of Black Gate’s vast Indiana Compound to continue my reading, not to surface more until my work is done.

Onward –– and remember: steer clear of Morgause.

Mark Rigney has published multiple pieces for Black Gate, including the perennially popular “Youth In a Box” and several stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library, including ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.”

Away from Black Gate, he is the author of the supernatural quartet, The Skates, Sleeping Bear, Check-Out Time, and Bonesy, all of which are now out of print, thanks to the demise of Samhain Publishing. (He is working to correct this injustice as fast as humanly possible.) His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Lightspeed, Unlikely Story, Betwixt, Black Static, The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Realms of Fantasy, Witness, The Beloit Fiction Journal, Talebones, Not One Of Us, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and many more. His author’s page at Goodreads can be found here, and his website is markrigney.net.

Thanks for this.

I seem to have read The Once and Future King three times, but the most recent reading was in 1980.

Before fantasy was really established as a publisher’s marketing niche, with innumerable authors turning out innumerable multi-volume series, White’s revisionist Arthurian book was one of the volumes everyone read, along with the books of Tolkien, Lewis, and other British authors, Beagle’s Last Unicorn, etc.

Since my last reading of White’s book, I’ve read the entire Morte d’Arthur of Malory once, and about 2/3 of it several more times. It should be interesting to return to White having had that experience. If I do, I wonder if I will stick with it. There is quite a bit of medieval Arthuriana I’d like to look into: Chretien de Troyes, Perlesvaus (The High History of the Holy Graal), Marie de France, Wolfram’s Parzival, Gottfried’s Tristan, the works attributed to Walter Map, etc. I think White pretty much stuck with Malory.

Readers might like to check out a series on Arthurian topics here:

https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2018/01/10/ia-by-dodds/

May I particularly draw attention to Martyn Skinner’s The Return of Arthur? This is a delightfully readable poem of about 550 pages set in the near future. It has satire, beauty of nature, interesting remarks on ESP, and considerable humor and wisdom. In some ways it will seem like, in some ways very unlike, White’s work. It’s not a retelling of Malory, but rather describes Merlin and Arthur coming to Britain after it has had another war and has become an oppressive state. I like it a lot, but it is not well-known.

https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2018/02/07/an-easy-to-read/

If there were enough interest, perhaps someone would reprint The Return of Arthur. If you look it up, go for the 1966 edition from Charles Dickens’s publisher Chapman & Hall, which gives the whole work.

No mention of the fifth book – The Book of Merlin – published posthumously, edited and with an introduction by White’s biographer Sylvia Townsend Warner. Suppressed by White, it does reveal how White wanted to turn the whole work into an anti-war piece. Was this book ever published over on your side of the pond or was it confined to the UK?

Major Wootton – I have some poetry to attend to, thanks!

NeilH – No mention by design. I expect I’ll post again as I finish the next two, and then move on to The Book of Merlin, which I have read at least three times. White was wrong to suppress it. It’s a beautiful, moving work, a gift for readers everywhere.