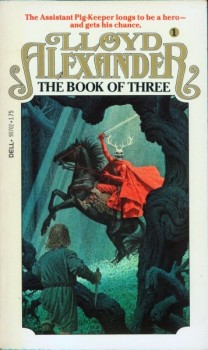

The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

Bear with me for a bit. With the death of Ursula K. Le Guin a few weeks ago, I began thinking about her Earthsea books. They were among the earliest non-Tolkien fantasy books I read. I loved them as a kid, I’ve read them three or four times since, and have fond memories of them. I’ll be looking at the first, A Wizard of Earthsea, next time. Thinking about those books got me thinking about a series I actually read even more times and have even fonder memories of: Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain.

Bear with me for a bit. With the death of Ursula K. Le Guin a few weeks ago, I began thinking about her Earthsea books. They were among the earliest non-Tolkien fantasy books I read. I loved them as a kid, I’ve read them three or four times since, and have fond memories of them. I’ll be looking at the first, A Wizard of Earthsea, next time. Thinking about those books got me thinking about a series I actually read even more times and have even fonder memories of: Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain.

Beginning with The Book of Three (1964), Lloyd Alexander created what has to be one of the first genre-fantasy uses of Celtic mythology (yes, Alan Garner had turned to Celtic themes in his Alderly Edge books, but those books are set in contemporary Britain, not a secondary world). Specifically, he drew on that complex and complicated compendium of Welsh tales, the Mabinogion, for inspiration and names. In this book, the four that follow, and a later collection of short stories, Alexander reworked the idiosyncratic legends into something any modern reader of fantasy would recognize immediately. Gone are the stories of women made from flowers, a human prince trading places with the god of the afterlife, and a king who is gigantic enough to wade to Ireland, and instead, a much more straightforward of a boy learning about the perils and responsibilities of heroism. Considering his intended audience was elementary school readers, it makes perfect sense to simplify, and to introduce a greater degree of coherence. I also imagine many young readers, like I was, were intrigued enough by Alexander’s books to track down the real legends.

In addition to being one of the earliest glosses on Celtic themes, The Book of Three is one of the first times Tolkien’s dark lord trope seeped into the genre. Instead of being a fairly benign lord of the afterlife as he is in the Mabinogion, Arawn is reconfigured as a mostly standard issue dark lord. The original’s mythic paradise, Annwn, is reconstructed here as a dread realm. Rereading The Book of Three for the first time in at least ten years, I was quite happy that I still enjoyed it, but seeing it with older eyes exposed gears and wires I hadn’t paid a mind to before.

Taran is an orphan being raised by the wizard Dallben and the farmer, Coll. Taran is about fifteen or sixteen and frustrated at being taught to forge horseshoes instead of swords, and tending to the oracular pig, Hen Wen, instead of learning how to fight. When he expresses his frustration to Coll, his guardian gives him a title:

“What is the use of studying much when I’m to see nothing at all?” Taran retorted. “I think there is a destiny laid on me that I am not to know anything interesting, go anywhere interesting, or do anything interesting. I’m certainly not to be anything. I’m not anything even at Caer Dallben!”

“Very well,” said Coll, “if that is all that troubles you, I shall make you something. From this moment, you are Taran, Assistant Pig-Keeper. You shall help me take care of Hen Wen: see her trough is full, carry her water, and give her a good scrubbing every other day.”

“That’s what I do now,” Taran said bitterly.

“All the better,” said Coll, “for it makes things that much easier. If you want to be something with a name attached to it, I can’t think of anything closer to hand. And it is not every lad who can be assistant keeper to an oracular pig. Indeed, she is the only oracular pig in Prydain, and the most valuable.”

Taran may seem to be every young farmboy dreaming of a heroic destiny, but Alexander undercuts that every step of his adventure. On one level, it’s obvious Taran will grow into some sort of actual hero — witness four more books — but nobility won’t come to him because of some innate right. Forced to learn, forced to pay for that education in loss and injury, forced to understand the extent of the price paid; among the hordes of pre-destined or noble characters infesting high fantasy, Taran remains a bracing breath of fresh air.

When the bees swarm and the chickens manage to take flight and abandon the farm, it’s clear something strange is going on. Coll goes to fetch the sticks Hen Wen uses to prophesy and Taran to fetch the pig. He finds her burrowing her way out of her sty and is soon chasing her into the forest. There he loses track of his charge and any sense of direction. At a loss for what to do, he is surprised by the sudden sound of horsemen, even more so when he sees who leads them:

He halted suddenly. Hoofbeats thudded in front of him. The forest shook as they grew louder. In another moment a black horse burst into view.

Taran fell back, terrified. Astride the foam-spattered animal rode a monstrous figure. A crimson cloak flamed from his naked shoulders. Crimson stained his gigantic arms. Horror stricken, Taran saw not the head of a man but the antlered head of a stag.

The Horned King! Taran flung himself against an oak to escape the flying hoofs and the heaving, glistening flanks. Horse and rider swept by. The mask was a human skull; from it, the great antlers rose in cruel curves. The Horned King’s eyes blazed behind the gaping sockets of whitened bone.

Escaping from the Horned King, Taran meets the warrior Gwydion. Gwydion was on his way to learn from Hen Wen how the Horned King could be defeated. Together, the two of them continue the hunt for the pig; a hunt that will lead them into great danger many times before it’s over.

The bare bones of the rest of The Book of Three involve Taran first attempting to find the pig and then trying to warn the High King, Math, that the Horned King and an army are secretly marching against him. His adventures, including escape from a dungeon, several run-ins with magical beings, and battle against Arawn’s undead soldiers, the Cauldron Born, don’t seem especially fresh now. I can’t believe, though, that when they were first written they were anything but. In 1964 there wasn’t all that much high fantasy, and none springs to mind that was written for children. 1964 is four years before A Wizard of Earthsea, six before Red Moon and Black Mountain, and ages before anything like Eragon. In a time practically overburdened by tons of juvenile fantasy, when plots, character types, and themes have been worked (and reworked) time after endless time, it’s easy to forget that there was an age before all that, when things were fresh and new.

The bare bones of the rest of The Book of Three involve Taran first attempting to find the pig and then trying to warn the High King, Math, that the Horned King and an army are secretly marching against him. His adventures, including escape from a dungeon, several run-ins with magical beings, and battle against Arawn’s undead soldiers, the Cauldron Born, don’t seem especially fresh now. I can’t believe, though, that when they were first written they were anything but. In 1964 there wasn’t all that much high fantasy, and none springs to mind that was written for children. 1964 is four years before A Wizard of Earthsea, six before Red Moon and Black Mountain, and ages before anything like Eragon. In a time practically overburdened by tons of juvenile fantasy, when plots, character types, and themes have been worked (and reworked) time after endless time, it’s easy to forget that there was an age before all that, when things were fresh and new.

Keeping that in mind, Alexander does a solid job of crafting an exciting story. It’s laden with indelible scenes and filled with memorable characters who push against the straitjackets of archetype and easy characterization. The book leaps, never illogically, from one scene to the next with steady pacing and ratcheting up of the sense of danger.

The most haunting events include Taran and Gwydion spying on the Horned King when he and his followers offer up human sacrifices, and Taran getting lost in the caverns under an ancient castle and winding up in the barrow of a long dead king:

They soon arrived at the end of the passage. Once more, fallen stones blocked their way, but this time there was a narrow, jagged gap. From it, the wailing grew louder, and Taran felt a cold ribbon of air on his face. He thrust the light into the opening, but even the golden rays could not pierce the curtain of shadows. Taran slid cautiously past the barrier; Eilonwy followed.

They entered a low-ceilinged chamber, and as they did, the light flickered under the weight of the darkness. At first, Taran could make out only indistinct shapes, touched with a feeble green glow. The voices screamed in trembling rage. Despite the chill wind, Taran’s forehead was clammy. He raised the light and took another step forward. The shapes grew clearer. Now he distinguished outlines of shields hanging from the walls and piles of swords and spears. His foot struck something. He bent to look and sprang back again, stifling a cry. It was the withered corpse of a man—a warrior fully armed. Another lay beside him, and another, in a circle of ancient dead guarding a high stone slab on which a shadowy figure lay at full length.

In considering the whole series, as much as I like The Book of Three — which is a lot — the thing about it I like best is its introduction to the primary  characters who will figure prominently in Taran’s life across the rest of the books. They, like Taran, evolve, and all get their moments in the spotlight.

characters who will figure prominently in Taran’s life across the rest of the books. They, like Taran, evolve, and all get their moments in the spotlight.

Foremost, there’s the princess, Eilonwy, who’s tart-tongued and fired up with a boldness based on knowledge and talent (unlike Taran’s impetuosity). Then there’s Fflewddur Fflam, a king who’d rather wander the lands of Prydain as a bard despite a marked lack of talent and an overwillingness to embroider the truth. Finally, there’s Gurgi, a creature built of equal parts Smeagol and rain-soaked mongrel. On the surface he’s a character of fun, using bad grammar and acting the coward, but Alexander makes him more than that, with someone telling Taran:

Gurgi’s misfortune is that he is neither one thing nor the other, at the moment. He has lost the wisdom of animals and has not gained the learning of men. Therefore, both shun him.

Too often, children’s books — heck, adult books as well — feature characters whose depictions never rise above a few easy traits. That’s not the case in The Book of Three, and even less so in the rest of the series. The great theme of the series is learning about responsibility and true honor, as well as the price that must oftentimes be paid for those things. It’s a theme always worth exploring, maybe even more so in this highly individualistic age than fifty-six years ago, and it’s woven into nearly every page of the book. Taran, a character introduced as a frustrated and impulsive teenager, is constantly made to confront his readiness to prejudge people and overestimate his abilities. Eilonwy, though she never gets a book to herself, undergoes the same maturation process.

The Book of Three is a brief book, lacking intricate worldbuilding often demanded of fantasy these days. Instead, it relies on well-limned characters and a wonderful sense of place and atmosphere. Alexander had been stationed in Wales for a short time during WWII and fell in love with it, and later with its legends. This affection carries over into his deeply evocative descriptions of the forests and mountains of Prydain, something he accomplished in barely 200 pages, not 1000.

The Book of Three remains one of the best works of high fantasy I’ve read. If you’re put off by reading a children’s book, don’t be. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed. In addition to telling a simple, good story with wonderful characters and more than enough imagination and originality, it also plays with and confronts some of the elements of a genre that was still forming. I just gave one of my nephews a copy and am waiting expectantly to hear what he thinks of it.

The Book of Three remains one of the best works of high fantasy I’ve read. If you’re put off by reading a children’s book, don’t be. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed. In addition to telling a simple, good story with wonderful characters and more than enough imagination and originality, it also plays with and confronts some of the elements of a genre that was still forming. I just gave one of my nephews a copy and am waiting expectantly to hear what he thinks of it.

As happy as I was to reread The Book of Three, I’m looking forward even more to revisiting the rest of the series. The second book, The Black Cauldron (1965), is a darker book with much grimmer consequences for some of its characters and the land of Prydain. It also introduces the scene-stealing three witches, Orddu, Orwen, and Orgoch. In The Castle of Llyr (1966) and Taran Wanderer (1967), Eilonwy and Taran come up against the obligations inherent to adulthood. The final book, The High King (1968), the darkest of all, lays bare the costs of peace and the near-unbearable weight of leadership in ways few children’s books have. I freely admit, every time I get to the end of The High King my eyes water up. I’m looking forward to seeing if that still happens. I strongly expect it will.

BONUS: I also just reread The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain (1982). Mostly told in a more fairy tale style, these stories explore the history of Prydain and provide origins for many of its major figures. I strongly recommend it as well, but definitely hold off until you’ve read the original five books.

WARNING: The Disney movie, The Black Cauldron (1985), is a very bad thing made of parts ripped from The Book of Three and The Black Cauldron and lacks any of the soul of Alexander’s work.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now.

This was a massive nostalgia trip for me. I don’t know why, but even from my earliest memories i was always into knights and dragons and things like that.

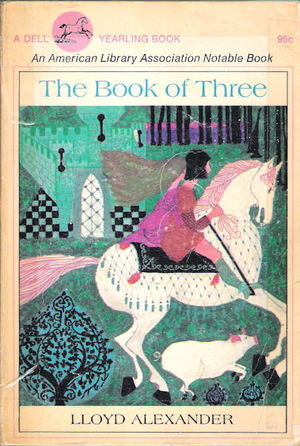

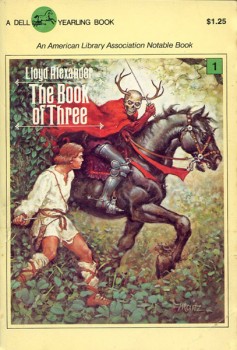

I can’t remember exactly what age I was when I read The Book of Three. Third grade maybe. My school library had a small hardback version of the Dell Yearling book $1.25 version). The skeleton looking knight was what grabbed my attention.

This was my first step into the fantasy genre. I loved it so much I read it twice. I don’t know why I never moved on to the other books in the series. Maybe its because this book was kind of beyond reading ability at the time.

The escape from the dungeon and the ending still stands out in my mind.

I bought the whole series 7 years ago. But sold it without ever reading any of them.

The Book of Three completely blew my mind at that young age.

The Prydain books, taken as a whole, constitute one of the the great achievements in fantasy, “children’s books” or not. I think they’ve been more influential than people realize. (David Eddings, for example.)

They’re also some of the best read-aloud books ever. If you ever need a fist-rate Gurgi or Fflewddur Fflam, just give me a call!

The Prydain books (in paperback) were among the first -books- that I ever bought for myself, when I was going beyond just keeping up with Marvel’s comic magazine releases every month. I’d first discovered them in the children’s section of the public library.

Those hardcover books were a pleasure to handle, nicely printed and bound, and I remember that the typography on the dustjackets appealed to me.

You can see it here:

https://www.thornbooks.com/pages/books/17089/lloyd-alexander/the-prydain-cycle-the-book-of-three-the-black-cauldron-signed-the-castle-of-llyr-taran-wanderer-and

I don’t know what that font is called, but I was excited, in my teens, to get hold of a sheet of film with that lettering, that one could rub off onto one’s own artwork.

I don’t know if other kids were the same way, but I certainly was intrigued by some fonts. Another that appealed to me was the one used on the Ace paperback Man from UNCLE novels and on innumerable Gothic novels and some sword-and-sorcery books (also a couple of Lancer editions of Lovecraft stories). See here the lettering for the title “The Monster Wheel Affair”:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2682932-the-monster-wheel-affair

But the typography on the Prydain hardcovers must’ve been just about the first font that really took my fancy. Does anyone know what that’s called?

I know that I read these books (along with John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy) about a million times when I was young; I just wish I’d actually kept notes so that I could remember when I first read these & the Narnia books, amongst others.

My favorite covers have always been the ones in the style of that Dell Yearling edition at the top of the page.

Indeed. I read the Prydain books repeatedly when I was quite young — starting around age 10 I think? They are wonderful. (And Alexander wrote some other very fine books, notably the Westmark series.)

My favorite was TARAN WANDERER.

I came to Earthsea slightly later — probably when I was 13 or so. I don’t want to rank them — I think both series are at a level where distinctions don’t matter: they are both great in their own way.

And, Joe — yes, the Tripods books are excellent too! And of course Narnia.

@Glenn – I’d say you were into knights and dragons because they’re freakin’ cool. I think you should give the rest of the books a whirl. It don’t believe it will dim your nostalgia any (always a fear in these sorts of situations), but actually burnish your memories.

@Thomas – I agree completely. Alexander based much of the description and personality of Fllam on himself.

@Major – I couldn’t begin to tell you about the fonts, though I bet if you wrote Henry Holt they would tell you. I can’t deny I have been swayed into purchases based on fonts types.

@Joe H. – The Dell Yearling covers – my favorites as well – are by Jean-Leon Huens. I just posted my favorites covers from each book at my site – https://swordssorcery.blogspot.com/2018/01/lloyd-alexander-art-of-the-prydain.html

Man, I haven’t read the Tripods in 20 years or more. I should dig them out as well.

@Rich H. – I’m really hoping to read Westmark this year.

Funny thing, I didn’t love Taran Wanderer as a kid, and now it’s my favorite. Same thing in Earthsea with Tombs of Atuan. Maturity and experience do interesting things to one’s tastes.

BONUS – there’s a good documentary about Alexander you can watch all of here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gocHqTToccY

I think this series was the first fantasy series I ever read. I loved it! I bought the Dell (from the late 70s/early 80s) a couple of years ago on Ebay. I was surprised how inexpensive yet what good shape the books were in.

Thanks for the post!

@James – You’re welcome!

I read the Chronicles of Prydain during high school. Loved them and stole liberally from them for gaming, but it might be thirty years since I last read them. (Alas, poor Taran, the Wizard of Earthsea is higher in my reread stack.)

@Jeff – Started rereading A Wizard of Earthsea and liking it still. Interesting contrast with Alexander’s approach to similar age-directed material

The High King was outstanding and remains one of my favourites 30 years later. The sense of the final battle, such a trope in many high fantasy books, was very real. The ending chapter touched on themes, including permanent change, consequence of choices and gradual disappearance into the mists of time, that I think few other young adult books touched on in quite the same way. Especially when the target audience is probably somewhere between 9-13 years old.