Fantasia 2017, Day 18, Part 2: Invasions Past, Present, and Yet To Come (Mumon, Bushwick, and S.U.M.1)

I ran up the steps in the Hall Building, hurrying from the basement where I’d just seen Geek Girls in the D.B. Clarke Theatre to reach the big Hall Auditorium in time to catch my second film of the day. The doors of the auditorium were still open, and I raced in and found a seat just as the movie began. It was called Mumon: The Land of Stealth (Shinobi no kuni), and I settled in knowing I had two more movies to see afterward. Mumon was a period film about ninjas fighting an invasion, and following that would come Bushwick, about residents of a Brooklyn neighbourhood fighting an invasion, then S.U.M.1, a German movie about people in a dystopian future fighting a (possible) invasion. A theme appeared to be emerging. (Two notes: one, Bushwick is now on Netflix in Canada and the US, so for those looking for a quick take on the film I’ll say that it’s a good enough movie I wish it were better; two, S.U.M.1 has now been given an expanded title, Alien Invasion: S.U.M.1.)

I ran up the steps in the Hall Building, hurrying from the basement where I’d just seen Geek Girls in the D.B. Clarke Theatre to reach the big Hall Auditorium in time to catch my second film of the day. The doors of the auditorium were still open, and I raced in and found a seat just as the movie began. It was called Mumon: The Land of Stealth (Shinobi no kuni), and I settled in knowing I had two more movies to see afterward. Mumon was a period film about ninjas fighting an invasion, and following that would come Bushwick, about residents of a Brooklyn neighbourhood fighting an invasion, then S.U.M.1, a German movie about people in a dystopian future fighting a (possible) invasion. A theme appeared to be emerging. (Two notes: one, Bushwick is now on Netflix in Canada and the US, so for those looking for a quick take on the film I’ll say that it’s a good enough movie I wish it were better; two, S.U.M.1 has now been given an expanded title, Alien Invasion: S.U.M.1.)

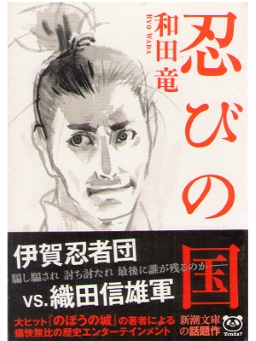

Mumon: The Land of Stealth was directed by Yoshihiro Nakamura (whose previous film The Inerasable I quite liked) and written by Ryou Wada based on Wada’s novel Shinobi no Kuni. It’s the sixteenth century, and Nobunaga Oda is trying to unify feudal Japan. Standing in the way is the Iga Province, home to the Iga ninjas who will kill anyone for hire. Most prominent among them is one Mumon (Satoshi Ohno), who is as lazy as he is skilled. But his amoral actions lead to a revenge-driven betrayal, setting up a battle between Oda’s forces and the ninjas of Iga. But who is one to cheer for in a battle of soldiers and contract killers?

There are some weighty elements to Mumon, posing questions about morality and loyalty and community spirit. Ninjas kill people for money, and being purely mercenary, the ninjas of Iga don’t immediately come together to make any kind of effective resistance to Oda. Mumon’s no exception, except perhaps insofar as his drive for financial reward comes about in part to keep his beloved wife Okuni (Satomi Ishihara, Hange in the live-action Attack On Titan films) in the style to which she is accustomed. The overall challenge, then, is for Mumon to grow as a person and rally his people as a community to fight off their invaders. That sounds like a fairly lightweight, if not simple, theme; but the movie goes some unexpected places.

For most of its running time it largely plays like a comedy. Mumon’s amiable and goofy, yet also the best there is at what he does, and all these characteristics are played for laughs. The incredible competence of ninja assassination skills in fact make for some excellent gags. Dialogue’s witty, and set-pieces are paced and edited like comedy bits. But there are darker elements; Oda’s son (Yuri Chinen), for example, has a powerful and dark scene confronting his nominal inferiors. And then near the end of the movie an action scene takes a turn, and the movie suddenly bursts into the realm of operatic melodrama.

For most of its running time it largely plays like a comedy. Mumon’s amiable and goofy, yet also the best there is at what he does, and all these characteristics are played for laughs. The incredible competence of ninja assassination skills in fact make for some excellent gags. Dialogue’s witty, and set-pieces are paced and edited like comedy bits. But there are darker elements; Oda’s son (Yuri Chinen), for example, has a powerful and dark scene confronting his nominal inferiors. And then near the end of the movie an action scene takes a turn, and the movie suddenly bursts into the realm of operatic melodrama.

I found it jarring. This may well be a function of cultural expectations and a cultural storytelling sensibility; I’ll also note that I spoke with other critics, more familiar with Nakamura’s previous work, who weren’t thrown at all by the turn the film takes. Personally, I found the comedy so front-and-centre for so long it was difficult to cope with the change in tone. There are undercurrents that in retrospect help prepare the ground for it, but the film dedicates most of its set-pieces ad big moments to comedy. That’s what it does well, and what it dedicates most of its time to. It effectively establishes a world in which goofiness is a central characteristic. Then decisively rejects that world near its climax.

There’s an odd parallel between that structure and the overall theme, I suppose. If the point of the movie is the way the various ninja characters come to find a deeper sense of meaning than mercenary gain, then one might argue that the movie reflects that by moving from light-hearted jokes about violence and murder to a deeper understanding of the pain of death. The problem there is that the jokes work too well. I found myself wanting to see more of the well-done humour than the relatively-standard melodrama.

There’s an odd parallel between that structure and the overall theme, I suppose. If the point of the movie is the way the various ninja characters come to find a deeper sense of meaning than mercenary gain, then one might argue that the movie reflects that by moving from light-hearted jokes about violence and murder to a deeper understanding of the pain of death. The problem there is that the jokes work too well. I found myself wanting to see more of the well-done humour than the relatively-standard melodrama.

It may be as well that the theme’s too simple to sustain that sort of weight. If the basic idea is exploring what it means to be human by seeing the evolution of (some of) the ninjas of the land of Iga, there’s not much depth to that exploration. The things we’d expect to be shown as good or bad are duly shown as such. A shot near the end drives the theme too clearly home to the modern day. I came away thinking that Mumon’s a fine movie for exactly as long as it doesn’t take itself seriously, which is a problem for a movie that has some serious ideas.

I will note that the ninjas, the novum of the movie — the gimmick, the thing you’re paying to see — are handled well, if with inconsistent power levels. Mumon himself is to the other ninjas of his village roughly what Marvel’s Thor is to other Asgardians; a much higher-level version of the standard. What makes him so good was unclear to me. Generally ninjas are good fighters, but as a group their lack of teamwork is a problem, which certainly plays to the movie’s theme. It’s an interesting way of presenting the Law of Conservation of Ninjutsu, or Law of Inverse Ninja Strength (under which one ninja’s almost unbeatable but a horde is cannon fodder).

As a film, Mumon is well-done. It’s paced well; its 125-minute run time flies by. The plotting’s dextrous up until the end, feeling logical and character-based while creating a variety of scenarios for Mumon to show his stuff in ways sometimes serious and sometimes not. The choreography of the fights struck me as scrambly, but the comic bits were very well-staged. I did have a sense of a tight budget here and there; what’s on screen works perfectly well, and there’s no lack of set-pieces, but there’s a sense of scale that’s overall lacking despite the occasional big battle scene. Conversely, there’s a higher ratio here of practical effects to CGI spectacle than I usually see these days (and it’s not impossible I’m reacting to that without being consciously aware of it). And a big multi-part battle near the end is well-handled, using terrain nicely.

As a film, Mumon is well-done. It’s paced well; its 125-minute run time flies by. The plotting’s dextrous up until the end, feeling logical and character-based while creating a variety of scenarios for Mumon to show his stuff in ways sometimes serious and sometimes not. The choreography of the fights struck me as scrambly, but the comic bits were very well-staged. I did have a sense of a tight budget here and there; what’s on screen works perfectly well, and there’s no lack of set-pieces, but there’s a sense of scale that’s overall lacking despite the occasional big battle scene. Conversely, there’s a higher ratio here of practical effects to CGI spectacle than I usually see these days (and it’s not impossible I’m reacting to that without being consciously aware of it). And a big multi-part battle near the end is well-handled, using terrain nicely.

Mumon: The Land of Stealth is a long but mostly entertaining movie that handles comedy quite well, but doesn’t get a bigger idea across without turning into a drama. I found the turn didn’t work, despite the best efforts of the cast. The comedy’s good enough that the movie’s worth watching just for the humour, but then one’s likely to be alienated by the dark aspects of the ending. It’s best watched, perhaps, by someone with a sense of story that can accept radical changes in tone and register.

From the Hall I then ran back downstairs to the D.B. Clarke Theatre, where I settled in to watch Bushwick. This film follows Lucy (Brittany Snow), a New Yorker who gets caught up in the fighting when a paramilitary force attacks the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Bushwick as part of a broader assault on the northern United States. Almost killed in the ensuing anarchy, she’s rescued by Stu (Dave Bautista), a giant with military and medical training, and together they try to make their way to safety. Standing in their way are mysterious invaders, random criminals, and excessively paranoid local residents. Hanging over the chaos is the question: who on earth invades Bushwick, of all places?

The movie gets a certain amount of mileage out of the question in its first half, as Lucy and Stu duck sinister black-clad and helmeted gunmen, but after it’s answered there’s a surprising lack of development. It turns out that a Texas-based insurgency is seceding from the Union, and launched a surprise attack on some northern cities to enhance its bargaining position. Massively improbable, sure, but it’s the relative good fortune of this movie that the idea feels topical (conceived seven years ago, production on Bushwick began in 2015, and post-production concluded last year). The problem is that once Lucy and Stu take a prisoner and find out what’s happening and who’s behind it all, nothing comes of the revelation. Stu, a former member of the American military, doesn’t seem to care much about the division of his country. Nobody even seems too surprised.

The movie gets a certain amount of mileage out of the question in its first half, as Lucy and Stu duck sinister black-clad and helmeted gunmen, but after it’s answered there’s a surprising lack of development. It turns out that a Texas-based insurgency is seceding from the Union, and launched a surprise attack on some northern cities to enhance its bargaining position. Massively improbable, sure, but it’s the relative good fortune of this movie that the idea feels topical (conceived seven years ago, production on Bushwick began in 2015, and post-production concluded last year). The problem is that once Lucy and Stu take a prisoner and find out what’s happening and who’s behind it all, nothing comes of the revelation. Stu, a former member of the American military, doesn’t seem to care much about the division of his country. Nobody even seems too surprised.

But then character is generally underplayed in this movie. You can understand why; it takes place mostly in real time, across a series of long takes digitally stitched together. The technical achievement’s the most remarkable part of the film. We follow Lucy almost entirely, the handheld camera following her as she runs one way and then another, up and down stairs; occasionally it whips around to show a gunfight, an explosion, some other menace approaching. It’s incredibly effective at conveying the adrenaline high that keeps Lucy going through all kinds of threats and dangers. And it’s all fast-paced enough that you don’t worry too much about logic or plot coherency — how likely certain reactions are, whether people should be going into shock, all that sort of thing. If you worry about that, you won’t be able to have the movie in anything like its current form. Lucy has to keep moving, not go catatonic with shock, and that’s all there is to it.

Unfortunately, the movie’s lack of concern with character undermines an excellent performance by Bautista. Snow’s Lucy is a fine protagonist, but Bautista’s quite remarkable, almost making us believe in his character’s shift from a self-involved loner to Lucy’s firm ally. Frustratingly, one of his best moments is undermined by the fact that the writing makes it an action movie cliché, telegraphing the next plot twist. Still, finding out about his character bit by bit is one of the real pleasures of the movie, something that gives a bit of needed balance to the formal dexterity of the long takes.

Bushwick’s greatest strength probably is that visual dexterity, though. For a low-budget movie, this is remarkably effective, using special effects deftly along with its frenetic handheld camerawork to create a very strong sense of house-to-house combat. We’re led on a quick walking-running-and-jumping tour of Bushwick, and the camera finds any number of interesting spaces — basements, stairwells, alleys, rooftops. Bautista’s used well, a constant looming presence, introduced first as a hulking shadow who gradually takes on recognisable human shape.

If you were to ask me what it’s all about, though, I wouldn’t be able to tell you very much. There are things that can be read into it, certainly. But nothing that dominates the story the way you’d expect of a major theme. So, sure, you could say it’s about political divisions in the United States; except one scene aside, that doesn’t really come across. You could say it’s about the experience of war, except there isn’t really much said about war as such. You could say it’s about Lucy finding inner strength she didn’t know she had, except that doesn’t emerge strongly as a theme and the ending tends to leave it moot. You could say it’s about the limitations of God and religion, on the basis of a well-shot and atmospheric digression into a church, but again that doesn’t come out much in the rest of the movie.

Probably the strongest theme, then, is about the community of Bushwick and how it unites when under threat. The movie seems to want to show that diversity is a strength. How the invaders find more unity than they’d been led to expect in a place known for its cultural variety. (The captured soldier who reveals the identity of the invaders says Bushwick was picked because the Texan war planners thought its diversity made it fragmented and weak.) The problem with reading the movie as a paean to diversity, though, is that every African-American in the film is in some way violent and threatening towards the two White leads. Which undercuts the idea of diversity as strength. Some more thought was really desperately needed about this aspect of the film.

Probably the strongest theme, then, is about the community of Bushwick and how it unites when under threat. The movie seems to want to show that diversity is a strength. How the invaders find more unity than they’d been led to expect in a place known for its cultural variety. (The captured soldier who reveals the identity of the invaders says Bushwick was picked because the Texan war planners thought its diversity made it fragmented and weak.) The problem with reading the movie as a paean to diversity, though, is that every African-American in the film is in some way violent and threatening towards the two White leads. Which undercuts the idea of diversity as strength. Some more thought was really desperately needed about this aspect of the film.

Still, it is true that the glimpses we get of the neighbourhood fighting back are interesting. I know nothing of Bushwick at all beyond the fact that it’s in Brooklyn (frankly, I’d never heard of the place before seeing the movie), but the sense of it as a community, as a place where people have roots, is engaging. At the same time, the film generates an effective sense of war coming to a major North American city, a documentary-like feel of a fundamentally incredible happening. As a story, it’s haphazard, and to my mind lacks an ending. But it succeeds at what it wants to do in terms of its cinematic form, which means it’s an engaging watch so long as you avoid thinking too carefully about character motivation or plausibility.

Still, it is true that the glimpses we get of the neighbourhood fighting back are interesting. I know nothing of Bushwick at all beyond the fact that it’s in Brooklyn (frankly, I’d never heard of the place before seeing the movie), but the sense of it as a community, as a place where people have roots, is engaging. At the same time, the film generates an effective sense of war coming to a major North American city, a documentary-like feel of a fundamentally incredible happening. As a story, it’s haphazard, and to my mind lacks an ending. But it succeeds at what it wants to do in terms of its cinematic form, which means it’s an engaging watch so long as you avoid thinking too carefully about character motivation or plausibility.

The next movie was across the street, in the De Sève Theater. It was an English-language German film called S.U.M.1, written and directed by Christian Pasquariello with a dialogue assist by Gabrielle Pfeiffer. In the future the Earth has mostly lost a war to invading aliens. Almost all of humanity lives in underground bunkers protected by a line of lonely towers guarding an electronic frontier against the monsters called the Nonesuch. Isolated soldiers man the watchtowers for tours of a hundred days at a time. There is one soldier per tower, and S.U.M.1 follows one of these soldiers through his tour. This soldier, S.U.M.1 (played by Iwan Rheon, Ramsay Bolton on Game of Thrones), is unusual: he dreams, which most of the human survivors in this future do not. And, as the days pass in an atmosphere of constant tension, he begins to doubt everything he’s been told. He finds evidence that something happened to his predecessor he wasn’t told about. He has mysterious conversations with a soldier at another tower. And he comes to wonder: is the Nonesuch threat real?

The next movie was across the street, in the De Sève Theater. It was an English-language German film called S.U.M.1, written and directed by Christian Pasquariello with a dialogue assist by Gabrielle Pfeiffer. In the future the Earth has mostly lost a war to invading aliens. Almost all of humanity lives in underground bunkers protected by a line of lonely towers guarding an electronic frontier against the monsters called the Nonesuch. Isolated soldiers man the watchtowers for tours of a hundred days at a time. There is one soldier per tower, and S.U.M.1 follows one of these soldiers through his tour. This soldier, S.U.M.1 (played by Iwan Rheon, Ramsay Bolton on Game of Thrones), is unusual: he dreams, which most of the human survivors in this future do not. And, as the days pass in an atmosphere of constant tension, he begins to doubt everything he’s been told. He finds evidence that something happened to his predecessor he wasn’t told about. He has mysterious conversations with a soldier at another tower. And he comes to wonder: is the Nonesuch threat real?

Rheon carries the film, virtually the only person onscreen for most of its 93-minute running time. He’s a good enough actor that he makes it work without turning the film into a vehicle for ostentatious displays of acting technique. But I did feel his character was somewhat underwritten. The movie doesn’t quite find enough ways to draw us into his head, or find enough original matter for his character. Rheon thus tends to get overwhelmed by the dark atmosphere around him; enclosed for much of the film in his concrete tower, he becomes almost a part of the brooding shadows that seem to be everywhere in the movie.

It’s important to note that the film’s shot and paced firmly like a genre piece about a man who might have stumbled on a mystery or might be going insane, not like an art-house movie exploring the psychic stress of isolation on a lone psyche. As such it’s effective, though I thought it’d work better if it were briefer and tighter; it’s the sort of story that’d work excellently as a Twilight Zone episode. It’s not original, but builds reasonably well to a solid ending — a drawn-out conclusion, but one that effectively pays off everything that’s been developed through the course of the film, showing the results of S.U.M.1’s final choice.

The film primarily lives in its atmosphere, and secondarily in Rheon’s acting. The world is sketched in nicely, if in broad strokes. It’s a delicate line: we have to doubt some of the basics of the world, just as S.U.M.1 does, so we have to be engaged enough with that world that the doubts have some meaning while being enough on the outside that we don’t know whether the doubts are correct. The movie’s successful insofar as that works — S.U.M.1’s fears and dilemmas come across clearly. The background feels like a lived-in world with other people in it, as opposed to a nightmare revolving around S.U.M.1.

The film primarily lives in its atmosphere, and secondarily in Rheon’s acting. The world is sketched in nicely, if in broad strokes. It’s a delicate line: we have to doubt some of the basics of the world, just as S.U.M.1 does, so we have to be engaged enough with that world that the doubts have some meaning while being enough on the outside that we don’t know whether the doubts are correct. The movie’s successful insofar as that works — S.U.M.1’s fears and dilemmas come across clearly. The background feels like a lived-in world with other people in it, as opposed to a nightmare revolving around S.U.M.1.

Which is interesting, insofar as S.U.M.1 is marked out as unusual by his atavistic ability to dream. That dreaming power is why the story happens to him instead to another soldier, why he comes to have doubts and feelings others don’t. It’s an interesting inversion of the usual way dreams are handled in most genre stories — dreams here are a way into horror, a kind of radical destabilising force, something that undoes a world, makes everything uncertain. I don’t know that the movie resolves this theme in an effective way, but it’s an interesting angle to take.

I will note also that there’s an interesting contrast between the modernist, almost industrial, architecture of the tower and the wild forest outside. There’s a sense of the wild as truly wild, encroaching on the human construction — which is itself a looming, brooding presence. Mysteries are found everywhere, inside and out; one could argue there’s a kind of gothic symbolism here, the tower as S.U.M.1’s psyche, the inhuman threat of the outside world matched by the implicit threat of the conspiracy S.U.M.1 stumbles on. And yet there’s a bit of the inhuman there as well, in the form of a rat S.U.M.1 adopts as a pet. Nothing’s wasted; Rheon gets something to act against, and when another character does enter the tower (André Hennicke), the rat becomes a point of dramatic conflict.

So the film moves along, well-constructed and tidy. It’s a solid low-budget science-fiction movie with a knack for atmosphere, a slow burn of a tale which pays off well if not spectacularly. I find I wish it had taken more risks, tried to carry more of its story in visuals without worrying about exposition. The sense of atmosphere and cinematic craft is so consistently strong I suspect it might have worked, and the basic set-up of a single character left alone in a wilderness as his sanity decays seems like it was made for a more ambitious kind of exploration. That might have required a different kind of vision than Pasquariello had for the film, of course. But there the basic tools are here; one thinks Rheon could have carried the film if it had wanted to go in that direction. A moot point, since it didn’t. It’s a decent film that feels like it could have been exceptional, and there are worse things than that.

After the film, director Christian Pasquariello came out to take questions. The first question was simply how the movie came about, to which Pasquariello said he started the screenplay seven years ago; unfortunately it’s hard to find genre financing in Germany, so it took him a while to find producers. He was then asked about star Iwan Rheon, who plays a completely different sort of character than he does on Game of Thrones. “Nice guy, isn’t he?” Pasquariello asked. “Don’t hate him!”

After the film, director Christian Pasquariello came out to take questions. The first question was simply how the movie came about, to which Pasquariello said he started the screenplay seven years ago; unfortunately it’s hard to find genre financing in Germany, so it took him a while to find producers. He was then asked about star Iwan Rheon, who plays a completely different sort of character than he does on Game of Thrones. “Nice guy, isn’t he?” Pasquariello asked. “Don’t hate him!”

A number of questions followed that had to do with the world or resolution of the film; I’ll summarise here what I can without giving too much away. Pasquariello confirmed that the ending of the film was what had always been planned. He said that part of the goal of the film was to present a twist on a certain conspiracy trope. He said that stragglers did not want to go to the underground base because for them it was better to die on the surface. He noted that the appearance of S.U.M.1 came from living underground, and since he never saw the daylight, he developed an albino-like coloration. And he noted that the dreams of the character established a reason for following the character and gave him a more human touch.

At one point Pasquariello said that he wanted to tell a story, but not the whole story. He wanted to let audiences make up their own mind. He spoke about the visual effects, saying that they were the longest part of the film to get done, being made by few people; he noted that if you have no money you need time. The actual shooting, he said in answer to another question, was done out of sequence in two sections, one dealing with interiors and one with exteriors. It was very prepared, as they didn’t have much time, and they’d storyboarded it out. Asked how he came up with the name “Nonesuch” for the character, he said it stuck in his mind from a short story he’d written; he liked the word because he found you could read anything into it.

At one point Pasquariello said that he wanted to tell a story, but not the whole story. He wanted to let audiences make up their own mind. He spoke about the visual effects, saying that they were the longest part of the film to get done, being made by few people; he noted that if you have no money you need time. The actual shooting, he said in answer to another question, was done out of sequence in two sections, one dealing with interiors and one with exteriors. It was very prepared, as they didn’t have much time, and they’d storyboarded it out. Asked how he came up with the name “Nonesuch” for the character, he said it stuck in his mind from a short story he’d written; he liked the word because he found you could read anything into it.

That concluded the day; and a solid enough day it had been. Fantasia was in its home stretch, now, with only three more days of films scheduled. As it happened, I had plans to be very busy at the festival over those days.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.