The Best of Cordwainer Smith, edited by J. J. Pierce

Do not read this story; turn the page quickly. The story may upset you. Anyhow, you probably know it already. It is a very disturbing story. Everyone knows it.

from “The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal”

Where to begin with Paul Linebarger, aka Cordwainer Smith? Son of a lawyer with ties to the Chinese Revolution of 1911, and godson of Sun Yat-sen, Linebarger, before World War II, was a professor of Eastern Studies at Duke. During the war, he served in the US Army and helped set up the first psychological warfare unit, and became an advisor to Chinese president Chiang Kai-shek. After the war, he was recalled to service to advise the British during the Malayan Emergency, and American forces during the Korean War. Later, he would serve in various intelligence capacities, calling himself “visitor to small wars,” though he avoided Vietnam, thinking it was a bad situation all around. Somehow, between the year 1950 and his death in 1966, he found the time and energy to create one of the most original, complex, and strange science fiction universes.

Where to begin with Paul Linebarger, aka Cordwainer Smith? Son of a lawyer with ties to the Chinese Revolution of 1911, and godson of Sun Yat-sen, Linebarger, before World War II, was a professor of Eastern Studies at Duke. During the war, he served in the US Army and helped set up the first psychological warfare unit, and became an advisor to Chinese president Chiang Kai-shek. After the war, he was recalled to service to advise the British during the Malayan Emergency, and American forces during the Korean War. Later, he would serve in various intelligence capacities, calling himself “visitor to small wars,” though he avoided Vietnam, thinking it was a bad situation all around. Somehow, between the year 1950 and his death in 1966, he found the time and energy to create one of the most original, complex, and strange science fiction universes.

As part of their “Best of” series, Ballantine published The Best of Cordwainer Smith in 1975, edited by J. J. Pierce. I picked it up in around 1984 at the Forbidden Planet in Manhattan, based on something I’d read recommending the story “Scanners Live in Vain.” Strange as I found it, “Scanners” was nothing compared to the mad, almost hallucinogenic stories that followed it. It contains twelve of of his most important stories, all set in the future history which he called the Instrumentality of Mankind. The Instrumentality is the group of supremely powerful humans who rule over humanity.

Cordwainer Smith (as I’ll call him from now on) first appeared in 1950 with the publication of the story “Scanners Live in Vain” (1950). Its frenetic start warns readers they are in for something strange.

Martel was angry. He did not even adjust his blood away from anger. He stamped across the room by judgment, not by sight. When he saw the table hit the floor, and could tell by the expression on Luci’s face that the table must have made a loud crash, he looked down to see if his leg was broken. It was not. Scanner to the core, he had to scan himself. The action was reflex and automatic. The inventory included his legs, abdomen, chestbox of instruments, hands, arms, face and back with the mirror. Only then did Martel go back to being angry. He talked with his voice, even though he knew that his wife hated its blare and preferred to have him write.

“I tell you, I must cranch. I have to cranch It’s my worry, isn’t it?”

Foremost from this opening is the word cranch. What can it possibly mean and why must Martel do it?

“Scanners” was rejected by numerous editors (including Dianetics-publishing William Campbell who called it “too strange”) before it found a home in Fantasy Book. It has since gone on to be anthologized numerous times and is generally considered a classic. In a foreword to another collection of Smith’s work, Fred Pohl describes how he tried to puzzle out which great writer was hiding behind such an obvious pseudonym:

“Scanners” was rejected by numerous editors (including Dianetics-publishing William Campbell who called it “too strange”) before it found a home in Fantasy Book. It has since gone on to be anthologized numerous times and is generally considered a classic. In a foreword to another collection of Smith’s work, Fred Pohl describes how he tried to puzzle out which great writer was hiding behind such an obvious pseudonym:

“Cordwainer Smith,” forsooth! The instant question that burned in my mind was who lay behind that disguise. Henry Kuttner had played hide-and-seek games with pennames in those days. So had Robert A. Heinlein, and “Scanners Live in Vain” seemed inventive enough, and good enough, to do credit to either of them. But it wasn’t in the style, or any of the styles, that I had associated with them. Besides, they denied it. Theodore Sturgeon? A.E. van Vogt? No, neither of them. Then who?

In 6000 AD humanity has spread to the stars, settling numerous extra-Solar systems. Early on it was discovered that traveling at near-relativistic speeds exposed humans to a feeling called the Great Pain, that induces suicidal feelings. To circumvent that, colonists are placed in suspended animation, and starships are crewed by Habermans and piloted by scanners. Both have had their senses, all save their eyes, severed from their brains, making them immune to the Great Pain. While the ordinary Habermans are criminals and dissidents, the Scanners are volunteers. Scanners alone are provided with the machines, implanted in their bodies, to monitor and fully control their actions — including their blood flow. They, also, are the only ones allowed to cranch. By means of a sketchily-described device, they can feel/smell/taste again, if only for a short while.

The story tells of the day when the scanners, revered and treated as Earth’s greatest heroes, learn their time may be coming to an end. A scientist has claimed he has found a way around the Great Pain, allowing anybody to pilot a space ship across. The fear of losing their power and prestige drives them to drastic ends. Only Martel, cranched during the meeting to decide what to do about the scientist, has empathy for the man, and the courage to face off against his fellow scanners.

“Scanners” serves as a perfect introduction to the wondrous, and often insane, universe of Cordwainer Smith. As with many of his tales, it dumps the reader into the middle of an alien setting filled with odd words and and characters. It gives a glimpse into a future history vastly stranger than and different from the usual empires and federations that litter so much of science fiction.

The remaining stories in the book are presented chronologically within the framework of the Instrumentality of Mankind, stretching from roughly 6000 to 16000 AD. Smith lays out a history that follows humanity up and out among the stars. After the scanners are rendered obsolete, great solar sail ships trailing thousands of colonists in sleep-pods ply the starways. Later, they are replaced by ships that planoform, that cross into extra-dimensional space, and jump light years in minutes. At some point over the millenia, the Instrumentality is established in order to protect humanity from the dangers of space and create a society of safety and happiness.

The first several stories following “Scanners” are possessed of moderately straightforward plots, but Smith’s style makes them anything but straightforward. “The Lady Who Sailed The Soul” recounts the nearly star-crossed romance between Helen America and Mr. Grey-no-more.

With its opening paragraphs, Smith does something that happens throughout the stories of the collection: tales are presented as legends that might possibly be true, and the events of other stories are hinted at. The very names of the characters are redolent of tall tales and myth. The stories of the Instrumentality are defiantly not naturalistic ones of intrepid explorers and bold space captains, instead being poetic explorations of love, suffering, and sacrifice.

With its opening paragraphs, Smith does something that happens throughout the stories of the collection: tales are presented as legends that might possibly be true, and the events of other stories are hinted at. The very names of the characters are redolent of tall tales and myth. The stories of the Instrumentality are defiantly not naturalistic ones of intrepid explorers and bold space captains, instead being poetic explorations of love, suffering, and sacrifice.

In a Cordwainer Smith story, it is not uncommon to find poems and song lyrics. Many of the stories, some modeled on Classical Chinese patterns, are told as if from a distance. Others, it is implied by the narrator, may not have happened at all, or at least not like the way it is remembered by most people. In this story we’re told that, unlike “the tall, confident heroine of the actresses who later played her,” Helen was “a grim, solemn, sad, little brunette” and Grey-no-more “prematurely old and still quite sick when the romance came.”

The dangers of interstellar travel are explored in the next two stories. In the absolutely wonderful “The Game of Cat and Dragon,” a pinlighter, a telepath that works in conjunction with a cat, fends off the brain-frying denizens inhabiting the regions the planoform ships traverse. “The Burning of the Brain” is about Dolores Oh’s terrible fear over the love of her husband, Go-captain Magno Taliano, and the disaster they face between the stars.

“The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal” and “Golden the Ship Was — Oh! Oh! Oh!” provide a glimpse into the majestic age of the Instrumentality. In the first, a captain is sent to explore the further regions of space. When he finds a lost human colony, only his commission of a grave transgression allows him to save Earth. In the second, the Instrumentality wages all-out war against a dangerous alien power that has the temerity to threaten Earth.

Several of the collection’s stories focus on the plight and struggle of the Underpeople. Although derived from animals, most, though not all, look like perfectly formed humans. Under the Instrumentality they have absolutely no rights. Any that fall ill or perform their tasks incorrectly are destroyed, as it’s cheaper to just replace them.

Derived in part from the story of Joan of Arc, “The Dead Lady of Clown Town” is about the first move towards emancipation of the Underpeople. It is told through the eyes of Elaine, a human who discovers a secret city of Underpeople. It is brutal, as is to be expected of any story about beings forced to exist under conditions of complete servitude and disregard. Still, it if suffused with moments of beauty and compassion.

“The Ballad of Lost C’mell” introduces the cat-derived C’mell. A girlygirl, a type of licensed geisha, she becomes a central figure in the plot to liberate the Underpeople. She would later figure as a major character in Smith’s one novel in the setting, Norstrilia.

Written in the sixties, there is a clear line between the struggle of the Underpeople and African-Americans’ struggle for civil rights. Like in the real world, it is a non-violent one that is met with viciousness and murder.

In “Under Old Earth,” the Lords of the Instrumentality become convinced that the utopia they have ushered in is a death sentence for humanity. Stripped of any uncertainty, danger, or incentive to do anything, really, the species is just fading away.

“Sorry,” said Sto Odin, “but I’m not violating a law. I’m making a point. We are sworn to uphold the dignity of man. Yet we are killing mankind with a bland hopeless happiness which has prohibited news, which has suppressed religion, which has made all history an official secret. I say that the evidence is that we are failing and that mankind, whom we’ve sworn to cherish, is failing too. Failing in vitality, strength, numbers, energy. I have a little while to live. I am going to try to find out.”

“Alpha Ralpha Boulevard” introduces the Rediscovery of Man. Old languages, religion, even diseases and money, are reintroduced to reinvigorate humanity. Paul and Virginia awaken to find themselves among the first people to be made French in this new age. Inspired by both the painting The Storm by Pierre Auguste Cot, and Smith’s own first wife’s attraction to another man, it is a sorrowful tale of love found and lost.

“Alpha Ralpha Boulevard” introduces the Rediscovery of Man. Old languages, religion, even diseases and money, are reintroduced to reinvigorate humanity. Paul and Virginia awaken to find themselves among the first people to be made French in this new age. Inspired by both the painting The Storm by Pierre Auguste Cot, and Smith’s own first wife’s attraction to another man, it is a sorrowful tale of love found and lost.

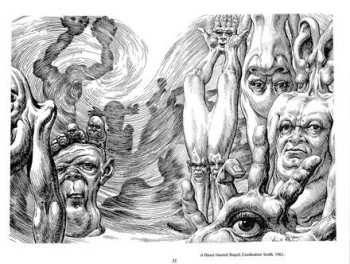

The other stories, “Mother Hitton’s Littul Kittons” and “A Planet Named Shayol” explore regions outside the direct purview of the Instrumentality. The first is the planet Norstrilia, sole source of the anti-aging drug, stroon. The richest planet, it becomes the target for the greatest thief of all time. Unfortunately for him, he is never able to learn the exact nature of the planet’s defenses. The second is the planet Shayol, to which only the greatest criminals are sentenced. Once on its surface, exposure to a microscopic native life form leads to the growth of new organs, limbs, even heads and torsos, from one’s body. These same organisms keep the prisoners alive in a state of often grotesque pain. Still, Smith crafts from this horrible scenario a story of love and devotion.

These synopses give a little hint at the power of these stories. They are wonderful, idiosyncratic, and often quite beautiful, and are jammed with images and names that will blaze in your psyche like few other things in sci-fi.

Some also ask big questions, particularly, what makes a person human? Sometimes it’s easier to look for answers to questions like this within the confines of of the fantastic. With bits of real life mixed with the trappings of science fiction, and told with perfectly chosen words, Smith created a cycle of beautiful futuristic myths. And still, his stories resound with humanity and empathy. There are few moments in science fiction as moving as the death of D’joan in “The Lost Lady of Clown Town” or heartbreaking as when Paul in “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard” gets his answer from the computer Abba-dingo. These stories have lingered in my mind for thirty years, and I know they will linger there for thirty more.

Note: Jame McGlothlin reviewed this book earlier this year HERE.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular.

Game of Rat and Dragon! Mother Hittons Littul Kittons! And Oh, so much more! Oh!

I have the complete collection, The Rediscovery of Man, and it is so worth buying. In my opinion, Linebarger was the greatest writer of science fiction stories ever.

The first story of his that I ever read, Game of Rat and Dragon was in a college textbook science fiction collection. It was probably the only story I had ever read that I felt could have been written by Fritz Leiber. I became an instant fan from that moment on.

Great article, Fletcher. Thanks!

[…] achievements in SF history. Recently there have been at least reviews of the John W. Campbell and Cordwainer Smith volumes. For more, see the list at the bottom of the Campbell review or perhaps these (mostly […]