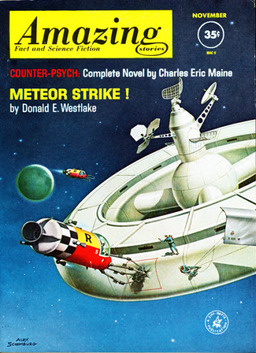

Amazing Stories, November 1961: A Retro-Review

This is an earlyish Cele Goldsmith issue. Unusually, it has only three stories.

This is an earlyish Cele Goldsmith issue. Unusually, it has only three stories.

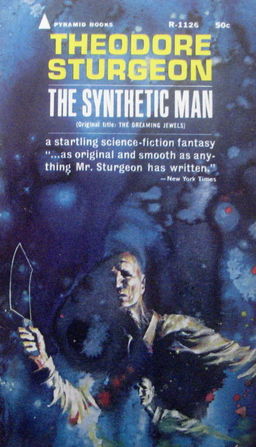

The editorial is given over to a reprint of part of an interview with an Emeritus Professor of Mathematics from New York University, Richard Courant, that had been published in Challenge. Courant is presented as something of a skeptic about computers, though as presented his skepticism seems sensible enough. The only other feature is a pretty short book review column (it was cut, and the lettercol eliminated, to make room for the complete novel in one issue). The books reviewed were Level 7, by Mordecai Roshwald, a once famous post-apocalyptic novel, now little-known, which S. E. Cotts praises highly in terms that make it sound absolutely dreadful; and The Synthetic Man, by Theodore Sturgeon, a novel better known as The Dreaming Jewels, which Cotts also likes. The cover is by Alex Schomburg, and the interiors are by Virgil Finlay and Dan Adkins.

A word about S. E. Cotts, the book reviewer for Amazing throughout most of Cele Goldsmith’s tenure. I have long wondered who Cotts was, and also whether Cotts might have been a woman. In recent correspondence, Robert Silverberg, who succeeded Cotts as Amazing’s book reviewer (after a one column appearance by Lester Del Rey), said that he thought (but was not sure) that S. E. Cotts was actually Cele Goldsmith’s sister. I have never heard that before, and it’s pretty intriguing. (We might note that Floyd C. Gale, book reviewer for Galaxy in the 1950s, was editor H. L. Gold’s brother.)

The cover story is a novelet, “Meteor Strike!”, by Donald E. Westlake (12,500 words). Westlake, who was born in 1933 and died in 2008, was one of the great crime fiction writers of our time. I am particularly fond of his comic capers featuring the thief John Dortmunder. Others plump for his darker novels about a criminal named Parker, written as by Richard Stark. Early in his career, Westlake published a fair amount of Science Fiction, before bidding a bitter farewell to the field in a rant published in the great fanzine Xero. Westlake complained about SF’s conservatism, and particularly about John Campbell. Alas, I feel his argument — which had some merit — loses some force simply because, truth be told, Westlake was a pretty mediocre SF writer.

That said, I did rather enjoy the last Westlake SF story I read, “The Risk Profession” (Amazing, March 1961). But it was in part a crime caper piece, playing to his strength. “Meteor Strike!” is pretty dire. It’s about a regular Earth to Moon transportation system, particularly a space station en route, and a regular delivery of something important to the lonely station orbiting the Moon. This particular flight includes three new spacemen, one of them a rather truculent young man, embittered by his flunking out of MIT. He’s pushed himself to success ever since, but at the cost of being a prime jerk.

That said, I did rather enjoy the last Westlake SF story I read, “The Risk Profession” (Amazing, March 1961). But it was in part a crime caper piece, playing to his strength. “Meteor Strike!” is pretty dire. It’s about a regular Earth to Moon transportation system, particularly a space station en route, and a regular delivery of something important to the lonely station orbiting the Moon. This particular flight includes three new spacemen, one of them a rather truculent young man, embittered by his flunking out of MIT. He’s pushed himself to success ever since, but at the cost of being a prime jerk.

This behavior continues on this trip. So when a meteor unconvincingly hits the Earth-orbiting space station (and embeds itself in its skin!), right where the precious cargo is stored, somehow this rookie is chose to assist in the repair operation. He does OK, of course, after some bad spots. And the suspense over the “cargo” is finally relieved — it’s entertainment tapes. Sigh. This is painfully earnest “hard” SF, overly complicated in a way to make it certain that many details will be embarrassingly wrong; and with a really badly strained character story behind it. You can see Westlake working hard to make his story serious — to make the science plausible and the characters three-dimensional.

But I think he missed the boat on both fronts. As I’ve said before, Westlake’s decision to concentrate on crime fiction was definitely the right one.

The “little known writer” is issue is Maurice Baudin, at least in SF terms. “Hystereo” (4,700 words) was his only story published in the genre. But he wasn’t unknown (though, these days, certainly little known): he published in places like the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, and had at least one story produced for the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV show. He also taught writing at NYU.

The story concerns Woodard, a man staying at a summer hotel in the woods, who doesn’t much enjoy his fellow guests. A mysterious drowning is alluded to, and a strange man who insists on demonstrating his record collection to the guests. Finally Woodard is inveigled into listening to this man’s records, which turn out to be a strange set of sound effects… leading to a macabre (and somewhat interesting if implausible) resolution. Minor SFish horror, but OK in its way.

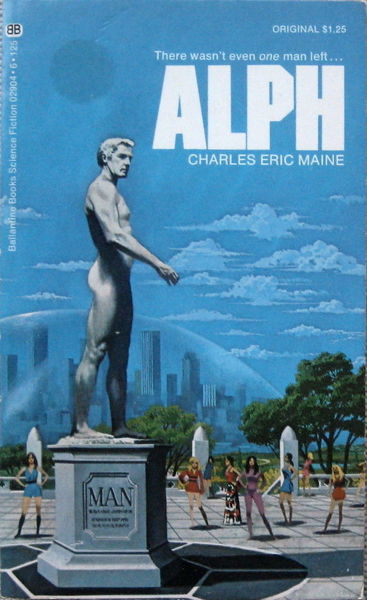

And finally the novel. Charles Eric Maine was the pseudonym used for his SF by David McIlwain (1921-1981), an early UK fan who also wrote detective stories as by “Richard Rayner” and “Robert Wade.” Maine never got a whole lot of notice — as John Clute and Peter Nicholls note in the Science Fiction Encyclopedia, he was “determinedly an author of middle of the road Genre SF” — with (perhaps not surprisingly given his detective writing background) a tendency towards thrillerish plots.

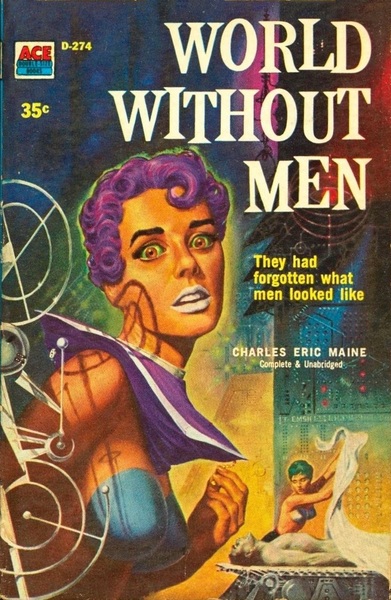

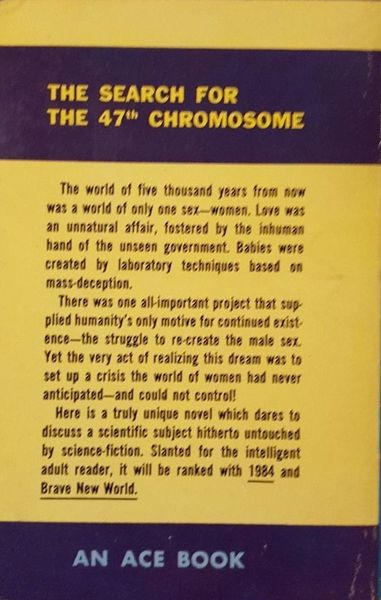

He wrote some 18 SF novels and a few short stories. I’m not very familiar with his work — I recall the book Alph from the early ’70s (though it was first published as World Without Men in 1958: I don’t know if Alph is revised or not); and also Timeliner, apparently considered one of his best stories. Clute and Nicholls plump for The Mind of Mr. Soames, which does look interesting (about a man who is unconscious from birth until age 30; it was filmed by Columbia Pictures in 1970, with Terence Stamp in the tile role).

|

|

|

“Counter-Psych,” which is some 31,000 words long, is one of four novels about Mike Delaney, a journalist for a popular science weekly called The View, who apparently gets into predicaments while investigating interesting new scientific phenomena. (I haven’t read the other three novels so I can’t say for sure, but that seems likely.) The other three novels in the series (The Isotope Man (1958), Subterfuge (1960), and Never Let Up (1964) were published by Hodder and Stoughton in the UK, though only the first seems to have had US editions (from Lippincott and from the SFBC). “Counter-Psych” has never been reprinted: I’m not sure why, unless it was too short to make a respectable book.)

The novel opens with Delaney and his girlfriend, Jill Friday, a photographer, hurrying back to the office — they’re late in filing copy for their current assignment. (It’s not said why they’re late, but I like to think they stopped off somewhere for a quicky.) Delany stops to make a phone call, and finds a notebook left by the previous caller. He tries to call the phone number in the book, and gets a curious response, followed by a promise to come pick up the book. But then the woman who had made the call returns, and Delaney gives her back her notebook. When the other character turns up, he refuses to believe that Delaney innocently gave the proper owner her book, and Delaney is kidnapped and beaten up. He manages to escape eventually from his kidnappers, a strange man with a scar around his scalp and a sadistic dwarf. Delaney can’t let this story go, and despite his editors’ insistence that he forget it and work on his late assignment, he investigates, visiting the woman to whom he gave the notebook.

He soon learns that the woman is married to a prominent scientist. The scientist had worked on neurology, discovering something called the “cerebrosome”, which is presented as part of the brain cells analogous to chromosomes. But know he is involved in a weapons project of some sort. And he seems psychologically unstable. Before long the wife turns up mysteriously murdered — and then she comes back to life. Delaney undercovers another murder (of the dwarf) and learns of an upcoming test in Australia of the scientist’s latest project. But is the scientist really insane? Or is he being unwillingly forced by the government to use his talents for weapons?

The ultimate revelation of the use of the “cerebrosomes” in weapons — essentially, to make “smart weapons”, as presented not much more interesting than things I myself have worked on (computer guided bombs) — is somewhat underwhelming. The plot is fast moving, in pure action thriller mode. There are holes, and the science is kind of silly, but it’s acceptable entertainment.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a Retro-Review of the May and June 1965 issues of Amazing Stories. His website is Strange at Ecbatan

I never knew Westlake wrote SF! Funnily enough, I’m re-reading ‘Two Much’ at the moment.

WORLD WITHOUT MEN isn’t completely forgotten:

https://orthosphere.wordpress.com/2013/12/14/world-without-men-a-novel-of-totalitarian-lesbiocracy/