Phoenician and Roman Cádiz: The Original Pillars of Hercules

Phoenician bling.Jewelry found in the Phoenician cemetery dating

from the 5th to 2nd centuries BC. The finds include many imports,

even amulets of Horus and Sekhmet from as far away as Egypt

Europe is known for its ancient cities, with many dating to Roman or even pre-Roman times. One of the oldest continually inhabited cities in Europe is Cádiz, on the southwestern coast of Spain near the Strait of Gibraltar. It has been a city since at least Phoenician times and has been of crucial importance to the region ever since.

More Phoenician bling

Linguists believe that the name of the city comes from the Phoenician word “Gadir” or “Agadir”, which means “walled area” or “stronghold”. Interestingly, there are still several towns names Agadir in Morocco. The name went through several changes as the city changed hands between the Greeks (“tà Gádeira”), Romans (“Augusta Urbs Iulia Gaditana”), Arabs (“Qādis”), until finally settling on the modern Spanish “Cádiz”. What it will be next depends on the next conquering civilization.

Cádiz sits on a large island reached by a narrow spit of land sheltering a fine harbor. The Phoenicians settled here around 1100 BC, but as with many Spanish cities, later structures were built right atop earlier ones, so little is known about the layout of any of Cádiz’s early periods.

His and hers anthropoid sarcophagi, of a style

popular in Sidon (in modern Lebanon) based on Egyptian models

Five terracotta busts from the Phoenician period, probably

representing Astarte, a popular goddess in Cádiz, c. 5th century BC

From ancient sources we do know that the most prominent landmark was the grand temple of Melqart, one of the leading gods in the Phoenician pantheon. Strabo noted that the two tall bronze pillars in the temple were thought by many Greek and Roman travelers to be the Pillars of Hercules, marking the westernmost extent of the hero’s travels while performing his twelve labors. Strabo refers to them as “the pillars which Pindar calls the ‘gates of Gades’ when he asserts that they are the farthermost limits reached by Heracles.” He also notes, however, that nothing on the pillars themselves linked the site to Hercules. The Greeks and Romans, always eager to conflate foreign gods with their own, had decided Melqart was Hercules.

“Anyone seen my pillers?” An ex voto of Hercules found without

context. Because these figurines were made for such a long period

of time, and the temple to Melqart/Hercules lasted a thousand

years, it is difficult to date

The city became a Roman possession in 206 BC after the Iberian campaign, and continued as an important network for trade. A large theater, proclaimed by local boosters as the second biggest in the Empire after Pompeii, is one of the only traces left of this time.

Luckily, the Spanish have been careful to excavate any time new construction reveals old foundations, and there’s an amazing collection of artifacts from all periods in the local archaeological museum. What’s shown here is only a taste of what this museum has to offer. Sadly, although Cádiz is a popular tourist destination, we had the place almost to ourselves!

Coming up next week: More on Cádiz!

Photos copyright Sean McLachlan. More below!

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles, including his post-apocalyptic series Toxic World that starts with the novel Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

Part of the Roman theater, covered by later buildings

The interior of the theater is quite well preserved, and you can walk all the way around

“Like a circle in a spiral. . .” Roman mosaic found at Cádiz

The corners of the mosaic are decorated with swastikas, a symbol that

has had its meaning unfortunately twisted in modern times

Roman-era toys

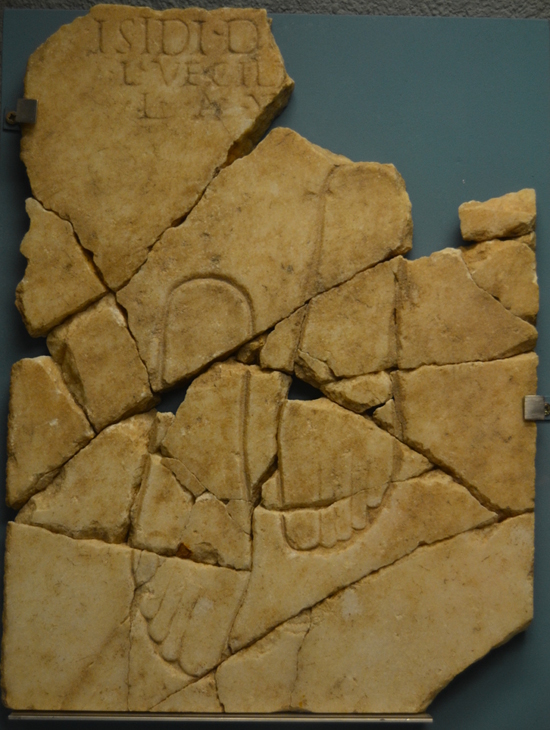

From the temple of Isis, venerated as a protector of sailors.

Her sanctuary at Cádiz contained many votive plaques, including this

marble slab with engraved feet and an inscription to the goddess.

The feet represent her physical presence in the temple

Roman phallic amulets for protection. They were

often worn by young children to ward off the evil eye

The Muslim period got rid of that phallic nonsense, but

saw a rise in trade as Cádiz flourished as part of the large Islamic empire.

These odd square dinars were common in the region

A fine bowl from the Islamic period

Those square dinars are really quirky. I wonder what the advantage of squareness was.

Did you find out more about what it meant to the people who venerated Isis to think of her as physically present? Those footprints put me in mind of stage markings — there are religions all over the world that include practices we might call spirit possession, with special locations or body positions to help clergy prepare to receive their deities.

The his and hers sarcophagi caption cracks me up. You may already know about the time Neiman Marcus offered his and hers mummy cases in their holiday catalog, only to discover that one of them still contained its original mummy.