Fantasia 2016, Day 8: Animated Critiques (Psychonauts, the Forgotten Children and Harmony)

There was one movie scheduled at Fantasia on Thursday, July 21 that I was determined to see: a science-fiction anime called Harmony (Hamoni). Since I had time free beforehand, I decided I’d first head to the festival’s screening room to watch something I’d missed or would be unable to see later. There, I looked over the selection available and settled on Psychonauts, the Forgotten Children (Psiconautas, los niños olvidados), an animated film from Spain. I liked the idea of a double feature of two very different cartoons.

There was one movie scheduled at Fantasia on Thursday, July 21 that I was determined to see: a science-fiction anime called Harmony (Hamoni). Since I had time free beforehand, I decided I’d first head to the festival’s screening room to watch something I’d missed or would be unable to see later. There, I looked over the selection available and settled on Psychonauts, the Forgotten Children (Psiconautas, los niños olvidados), an animated film from Spain. I liked the idea of a double feature of two very different cartoons.

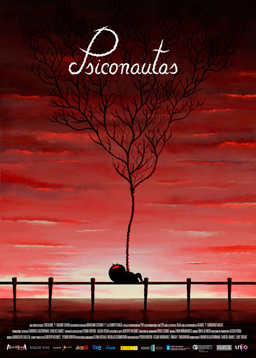

Psychonauts is an engagingly complex movie that takes place on an unknown island, in the ruins of an industrial-age civilisation: many children go to schools, there’s a police force and a sort-of-functioning economy, but also any number of scavengers living in vast tracts of trash shaped by hills of garbage. This story isn’t to be understood as science-fiction, though, since on this island there are also monsters, separable souls, and demonic shadows. Birdboy, a mute child with the power of flight (more or less), seems to know some of the secrets of this strange place. A girl, Dinky, knew Birdboy once and still loves him. She hopes to leave the island, but won’t go without Birdboy — even though the authorities are out to get him, blaming him for selling drugs to children. The movie follows both Birdboy and Dinky as they go about their separate ways, encountering the strange societies of the island and exploring its mysteries.

Psychonauts is technically the sequel to an earlier short film, “Birdboy,” which I have not seen (and does not seem necessary to understanding Psychonauts). Both movies were co-written and co-directed by Alberto Vazquez and Pedro Rivero, based on a graphic novel by Vazquez. Psychonauts has something of the look of an indie comic, in the primitivist-yet-engaging design of its characters and the odd details of its backgrounds. If I had to point to a work in any medium which felt most like Psychonauts, I’d probably select Jim Woodring’s comic Frank, with its dreamlike, occasionally violent, and oddly complex stories. Psychonauts is an equally individual work, but has the same knack for creating oneiric symbols out of its settings and imagery.

An abandoned lighthouse with links to Birdboy’s past feels like Roland’s dark tower. A deep forest contrasts with the labyrinthine wasteland. Caves are hidden paradises or places of hopeless bargaining. Through these places and many others move the anthropomorphic animal characters, simple and sympathetic designs yet also strange. Backgrounds are expressionistic, colours evocative. Slowly, we come to learn along with the protagonists how complex their world is.

An abandoned lighthouse with links to Birdboy’s past feels like Roland’s dark tower. A deep forest contrasts with the labyrinthine wasteland. Caves are hidden paradises or places of hopeless bargaining. Through these places and many others move the anthropomorphic animal characters, simple and sympathetic designs yet also strange. Backgrounds are expressionistic, colours evocative. Slowly, we come to learn along with the protagonists how complex their world is.

The island seems random at first, a jumble of concepts. Part of the experience of watching the film comes from piecing together the systems that underlie what we’re watching, learning how the disparate things we see interrelate and interact. We as an audience are put in the position of the children who are the main characters, made to empathise with their childlike perception of the world: a place with weird rules that only become clear by observing others. We must guess at what is normal and what is not by what the young characters do, meaning they are more mature than us because they know at a certain basic level how to negotiate their environment. We become like children, watching children moving in an adult world.

And this is a very adult society, with drugs and mental illness. Sexuality is relatively subtle, and religion almost absent — there’s a Baby Jesus doll, one of the few hints of a cultural connection to our everyday world, but not much beyond that. Instead there’s a mythology of the island’s golden age, tales and legends of a better past, which we in the audience know to be untrue: an early monologue about the glories of the days gone by is voiced over a flashback sequence showing us what past life was actually like. Still, there is a persistent theme in the movie of hope, of searching for meaning or at least for a kind of escape or transcendence. We soon learn that among the island’s secrets there is a kind of paradise, an obscured salvation. Whether the characters will find their way to it is an open question.

And this is a very adult society, with drugs and mental illness. Sexuality is relatively subtle, and religion almost absent — there’s a Baby Jesus doll, one of the few hints of a cultural connection to our everyday world, but not much beyond that. Instead there’s a mythology of the island’s golden age, tales and legends of a better past, which we in the audience know to be untrue: an early monologue about the glories of the days gone by is voiced over a flashback sequence showing us what past life was actually like. Still, there is a persistent theme in the movie of hope, of searching for meaning or at least for a kind of escape or transcendence. We soon learn that among the island’s secrets there is a kind of paradise, an obscured salvation. Whether the characters will find their way to it is an open question.

The conclusion is bleak and yet also finally alive to hope. It fits the movie overall: harsh, filled with the cruelty of living in a world of scarcity, yet also optimistic and conscious of beauty. Violence in this film tends to lead to violence. But we are shown that there may be other options. It’s possible to see Birdboy as a Chistlike figure, persecuted by the authorities, the police, precisely for bringing hope to the world. As in the Christian story, the hope coexists with tragedy.

Authority figures in Psychonauts view hope as a drug. Specifically, as an illegal drug, in contrast to the pills Dinky’s parents feed her to keep her happy. If you’ve invested in the hierarchy of the island, hope of a better way of being is dangerously subversive. If you’re a child, on the other hand, you’re bound by the upbringing you get, and likely to be streamed into a violent way of life either because you haven’t been taught the damage you’re doing (as we see with a junior police officer) or because that’s all you’re left with.

Authority figures in Psychonauts view hope as a drug. Specifically, as an illegal drug, in contrast to the pills Dinky’s parents feed her to keep her happy. If you’ve invested in the hierarchy of the island, hope of a better way of being is dangerously subversive. If you’re a child, on the other hand, you’re bound by the upbringing you get, and likely to be streamed into a violent way of life either because you haven’t been taught the damage you’re doing (as we see with a junior police officer) or because that’s all you’re left with.

One way or another, the film is about children. Children are its main characters. Children repressed by parents, orphaned children, forgotten children who live in trash and must find their way through the garbage that chokes the world — forgotten children who, we are told, live off the rubbish and pain of others. Children who seek a better world in the wrong place, trying to leave their environment rather than heal it. This isn’t necessarily a story for children, but neither is it a simple coming-of-age story.

The natural world of the island is at heart restorative. The trick for the children is in coming to see this, to realise that there is hope in the place where they grew up. And in overcoming their demons to reach this realisation, or if not to overcome them at least to come to terms with them. There is much in Psychonauts to do with altered mental states, artificial or otherwise. With dreams, or with madness. In more ways than one, the movie follows sailors on the seas of the psyche. It’s possible, perhaps, to see the film as a kind of Jungian fable of psychological integration. But then it’s possible to see the movie as very many things. That’s the nature of fable and symbol: to bear many interpretations, but to always feel as if there’s more to be dug out of it. Psychonauts has the bottomless feel of a dream.

The natural world of the island is at heart restorative. The trick for the children is in coming to see this, to realise that there is hope in the place where they grew up. And in overcoming their demons to reach this realisation, or if not to overcome them at least to come to terms with them. There is much in Psychonauts to do with altered mental states, artificial or otherwise. With dreams, or with madness. In more ways than one, the movie follows sailors on the seas of the psyche. It’s possible, perhaps, to see the film as a kind of Jungian fable of psychological integration. But then it’s possible to see the movie as very many things. That’s the nature of fable and symbol: to bear many interpretations, but to always feel as if there’s more to be dug out of it. Psychonauts has the bottomless feel of a dream.

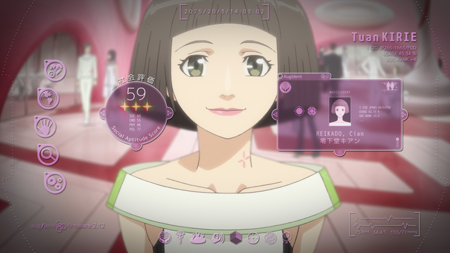

Harmony is something very different. It’s directed by Takashi Nakamura and Michael Arias, and written by Koji Yamamoto from a book by science-fiction writer Project Itoh (Satoshi Ito). A fascinating if sometimes uneasy mix of sf and mystery, it follows Tuan, who at the start of the film is an agent of the World Health Organisation observing a cease-fire in Niger between the government and Tuareg rebels. Things go poorly, There are flashbacks to Tuan’s youth, when she was part of a suicide pact with two other girls; only one of the girls, Miach, actually killed herself. It was an act of rebellion against an increasingly intrusive biomedical monitoring system — the same thing the Tuareg are fighting against. Tuan’s sent by her superiors back to Japan to “relearn how to live in a community.” She meets the other survivor of the pact, and coincidentally enough things start going terribly wrong. Terrorists cause suicides and murders. Society can’t handle the strain. Tuan has a limited amount of time to find out what’s going on, and how her dead friend is connected to the spreading violence.

This is a visually lush movie. It may be the most purely spectacular film I saw at Fantasia this year, and indeed for some time before that as well. Tuan’s future is highly detailed, and highly varied — the action shifts from Africa to Japan to Baghdad to central Asia, and every location has a distinct feel and design. Future Japan looks like no other cinematic science fiction city I’ve seen, organic yet pastel, with the characters viewing it through augmented reality overlays. The future Baghdad has both a monumental medical facility and a sprawling street market; it’s an embodiment of the division between the regulated world Tuan’s somewhat unwillingly defending, and the wilder but freer world beyond. The animation’s always excellent, and the action, when it comes, is marvellously fluid and quick.

This is a visually lush movie. It may be the most purely spectacular film I saw at Fantasia this year, and indeed for some time before that as well. Tuan’s future is highly detailed, and highly varied — the action shifts from Africa to Japan to Baghdad to central Asia, and every location has a distinct feel and design. Future Japan looks like no other cinematic science fiction city I’ve seen, organic yet pastel, with the characters viewing it through augmented reality overlays. The future Baghdad has both a monumental medical facility and a sprawling street market; it’s an embodiment of the division between the regulated world Tuan’s somewhat unwillingly defending, and the wilder but freer world beyond. The animation’s always excellent, and the action, when it comes, is marvellously fluid and quick.

Unfortunately, there isn’t very much of that action. This is a surprisingly languid movie, given the depth and density of the imagined future. The story’s slow to develop, and then consists mainly of Tuan travelling around talking to people. There aren’t any red herrings, and few challenges beyond the very occasional action set-piece. It’s very linear, and if to an extent that’s understandable given its other complexities — particularly the sheer number of science-fictional concepts it puts forward — it still results in a leisurely pace that isn’t quite meditative enough to work.

Then again, the movie aims high. The science-fictional ideas don’t just reflect present-day issues such as privacy versus security, but also more profound concepts such as the nature of the human self. It’s big-picture filmmaking in a very science-fictional way, profoundly symbolic while also being concrete enough to feel real. Most of the imagined future works splendidly, in that we can understand how it came about and in that it feels like an inhabited place; though it has to be said some ideas (such as a previously-undiscovered ethnic group) are introduced too late in the film to feel wholly integrated into the tale.

That said, the familiar conflict of an overly-intrusive society against dangerous individual freedom is dramatised well. There’s a balance here in which the high-tech world of people monitored every waking and sleeping moment is made to feel credible — the monitoring systems really do work to keep people safe and healthy. You know why most people would want to have them around. Conversely, although the point’s not highlighted, the violence in the film does come in the parts of the world where there is no monitoring. The feel of society as a gilded cage comes across, and if the alternative is romanticised, it also feels believably threatening.

That said, the familiar conflict of an overly-intrusive society against dangerous individual freedom is dramatised well. There’s a balance here in which the high-tech world of people monitored every waking and sleeping moment is made to feel credible — the monitoring systems really do work to keep people safe and healthy. You know why most people would want to have them around. Conversely, although the point’s not highlighted, the violence in the film does come in the parts of the world where there is no monitoring. The feel of society as a gilded cage comes across, and if the alternative is romanticised, it also feels believably threatening.

What brings out much of the poignancy is a flashback sequence to the three girls talking about their dissatisfaction with their society’s highly-developed medical protocols. Their bodies are being observed, if only by computer, and controlled. They can’t get fat, they can’t die, and (we’re told) even the growth of their breasts is being monitored. It raises the question of who really controls their bodies; and therefore whether in this future self-willed death is actually a radical assertion of freedom. (It is perhaps also worth remembering that the original novel was published as the author was hospitalised with the cancer that would soon kill him.)

Then that in turn calls up questions of the individual versus the society, and indeed what the individual ultimately is. If the ego, as someone suggests to Tuan, mediates competing desires within the psyche, what happens if a better way can be found to harmonise those desires? Tuan’s quest takes on profound philosophical overtones. In order to solve the mystery she’s got to answer basic questions of human nature, or at least understand the answers others have come up with. And that is to say she’s got to confront different ideas of what it is, in the end, to be human.

Then that in turn calls up questions of the individual versus the society, and indeed what the individual ultimately is. If the ego, as someone suggests to Tuan, mediates competing desires within the psyche, what happens if a better way can be found to harmonise those desires? Tuan’s quest takes on profound philosophical overtones. In order to solve the mystery she’s got to answer basic questions of human nature, or at least understand the answers others have come up with. And that is to say she’s got to confront different ideas of what it is, in the end, to be human.

Harmony sets higher store on science-fiction than it does on mystery or action, and that works because the science-fiction elements mesh perfectly with character. Tuan’s story becomes increasingly personal, for all the spectacle on display. The climactic scene isn’t a major set-piece but a very individual confrontation in which Tuan has to make a final choice, one which brings together all the themes the movie’s touched on. That’s a structural gambit that works, a distillation of the world down to one moment on which everything turns: a very science-fictional plot technique.

Literate — with explicit references to Goethe and Michel Foucault — and visually splendid, Harmony presents some of the most wondrous science-fictional imagery I’ve seen in a long time. It has an epic feel, if often a very slow pace. It deals with ideas and with character, and if it never catches fire as a mystery, the ambition and imagination deserve respect. It’s not a total success, but something worth watching, especially for science-fiction fans.

Literate — with explicit references to Goethe and Michel Foucault — and visually splendid, Harmony presents some of the most wondrous science-fictional imagery I’ve seen in a long time. It has an epic feel, if often a very slow pace. It deals with ideas and with character, and if it never catches fire as a mystery, the ambition and imagination deserve respect. It’s not a total success, but something worth watching, especially for science-fiction fans.

By the end of the day, then, I’d seen two excellent animated movies that both put highly distinctive visions on screen and both challenged society. Both, coincidentally, had female protagonists — girl in one case, grown woman in another — who had to understand the world around them. Psychonauts had, I thought, a more incisive critique, but Harmony was more visually lush. On the other hand, Psychonauts aimed at something different, more dreamlike; and Harmony’s critique of society was in service of the analysis of even broader issues of human nature. I’m drawn more to Harmony by instinct, but I think Psychonauts is more complete and less flawed. I’m glad I saw both.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.