The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Navajo Sherlock Holmes – Joe Leaphorn

Last week, we had something of an introduction to Tony Hillerman and his Navajo Tribal Police novels. A quick read before continuing on here might serve you well. Or, you can throw caution to the wind and keep going!

In July of 1945, Hillerman was was on a sixty day convalescent furlough from World War II, with a patch over a damaged eye and a cane to assist his gimpy leg. He had been wounded near the German village of Niefern. Carrying a stretcher under fire, he had stepped on a mine. Now being carried himself on a stretcher, the man holding the front stepped on a mine and Hillerman was on the ground again. Someone picked him up in a fireman’s carry, dropped him in a creek, got him to a jeep and laid him across the hood. Hillerman made it out, alive (He would receive the Bronze Star, the Silver Star and the Purple Heart for his service).

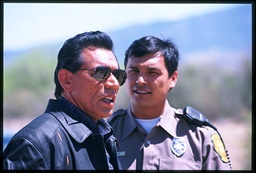

Now temporarily back in the States, he had gotten a job driving pipe from Oklahoma City to an oil well drilling site on the Navajo checkerboard reservation. He stopped as a stick carrier’s camp crossed the road in front of him. They were making the ritual delivery of a scalp to the camp of a Navajo serviceman receiving an Enemy Way ceremonial. That’s a bit different than a deer crossing the road!

Hillerman’s first novel, some twenty years later, heavily involved an Enemy Way (that was his choice for the title. His publisher selected a completely unrelated ceremonial, The Blessing Way).

Tony Hillerman had been a reporter for many years and had also written nonfiction when he decided to write his first novel. As influences, he has cited Ross MacDonald, Raymond Chandler, George V. Higgins, Ernest Hemingway (“when he was still young enough to care about it”), Graham Greene and Eric Ambler (a master of suspense who has become unfairly forgotten over the years).

A less familiar name is that of Arthur Upfield, who wrote about the Australian Aborigine, Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte. Hillerman frequently cited Upfield’s ability to make the setting seem real. That same descriptive ability is at the core of the Leaphorn and Chee books.

And speaking of those books…

“I was writing episodically because this short book stretched about three years from 1967 to 1970 from first paragraph to final revision – with progress frequently interrupted by periods of sanity – probably induced by fatigue and sleepiness. Most of my efforts at fiction were done after dinner when the kids were abed, papers were graded and the telephone wasn’t ringing.

Sometimes, in those dark hours, I would realize that the scene I finished was bad, the story wasn’t moving, the book would never be published, and I couldn’t afford wasting time I could be using to write nonfiction people would buy.

Then I would pull the paper from the typewriter (remember those?), put the manuscript back in the box, and the box on the shelf to sit for days, or some times a week, until job stress eased and the urge to tell the story returned.”

That was actually the first thing I put on paper for a Hillerman post. And what you’re reading today was intended to be the first and only post. But there was too much to talk about, so I moved that quote to an introductory post. I like it because it shows us Hillerman’s understated humor while presenting his tenacity. It took three years, but he finished The Blessing Way. And he kept the ‘Navajo stuff’ even though his editor told him to drop it.

Bergen McKee, a university anthropologist, is the protagonist of The Blessing Way. The story is actually about him. Hillerman placed the story on a Navajo reservation because he didn’t know if he was capable of writing a good mystery story, and it would at least have an interesting setting that way.

In the first draft, Leaphorn was a very minor character. When Harper & Row accepted the book (after Hillerman’s own agent refused to take it on: see that first post) but required Hillerman to write a different ending, he did more than that. As he revised his manuscript, Leaphorn’s role grew until the Navajo became the number two character in the book, though still not on equal footing with McKee.

The first three books are about Leaphorn. Then, Hillerman introduces a younger officer, Jim Chee, and he is in the next three novels. In book seven, Leaphorn and Chee are brought together in Skinwalkers, setting the tone for the rest of the series. Leaphorn is older than Chee, but a less traditional Navajo, who believes more in evil than in witches. Chee is young, but respects the old ways and is training to become a yataalii. That is, a singer who conducts Navajo healing ceremonies. Hillerman reverses the traditional conventions to good effect.

Leaphorn is a methodical man and Hillerman combines this with the Navajo concept of hozho (the concept of walking in balance in the world – maintaining harmony). In The Blessing Way, Hillerman writes, “That would have been luck. Leaphorn never counted on luck. Instead, he expected order – the natural sequence of behavior, the cause producing the natural effect, the human behaving in the way it was natural for him to behave.

He counted on that and upon his own ability to sort out the chaos of observed facts and find in them this natural order…and it was a talent which caused him, when the facts refused to fall into the pattern demanded by nature and the Navajo Way, acute mental discomfort.”

For me, this sense of order and logical consistency is exemplified by the Indian Country Map tacked up on the wall of his office. It’s from the Southern California Auto Club. It has up to a hundred colored pins spread out, representing different types of crimes throughout the reservations. He looks for clusters and linkages to help him think through problems. The other policemen think it’s a sign of eccentricity, but it’s a visual depiction of Leaphorn’s thought process.

Witchcraft is a common theme in the stories and is deftly handled. Suspicion of witches (not the “double double, toil and trouble” kind) as the source of trouble is something Leaphorn commonly runs into. Though he was raised as a traditional Navajo, he stopped believing in witches while at college. Now, Leaphorn believes in evil. But his dismissal of witches in an early case led to deaths and he learned not to discount the belief of others in them while investigating a case.

Witchcraft is a common theme in the stories and is deftly handled. Suspicion of witches (not the “double double, toil and trouble” kind) as the source of trouble is something Leaphorn commonly runs into. Though he was raised as a traditional Navajo, he stopped believing in witches while at college. Now, Leaphorn believes in evil. But his dismissal of witches in an early case led to deaths and he learned not to discount the belief of others in them while investigating a case.

The Blessing Way is a good book, but it is clearly, to me, the least of the series. It’s about Bergen McKee, not Joe Leaphorn. Hillerman acknowledges that he didn’t work hard enough on the Navajo elements (‘Leaphorn’ actually comes from a book on Cretan culture that Hillerman had read and has nothing to do with American Indians). The ending still needs a bit of work.

It suffers in comparison to the succeeding books: Certainly to Dance Hall of the Dead, the next Leaphorn book, which won an Edgar Award. I do not, however, agree with Ernie Bulow’s assessment in Talking Mysteries: “Sorry to say, the book was a terrible disappointment…It was something like reading a student paper with a lot of vocabulary freshly mined from a thesaurus.”

In Dance Hall, there is not a non-Navajo protagonist. A boy practicing for a Zuni ceremonial has gone missing and only a large pile of blood was found. Then his best friend goes on the run and Leaphorn is tasked with finding the second boy, who is a Navajo. It’s impressive that Leaphorn shifted from the Navajo to the Zuni religion for this one. The Dance Hall of the Dead is the place where the good souls go in the afterlife to dance and celebrate.

But why switch when Hillerman had just spent so much time learning about Navajos for the first book? “Because one of the galling examples of the American ignorance of tribal cultures is the notion (pervading movies, television and the media in general) that all Indians are alike. I set about to dent this ignorance by moving Leaphorn a hundred miles south to the Zuni reservation…I would force anyone trying to follow the plot to learn along with Leaphorn quite about the kachina sprit world and the Zuni cultural system. One thing such folks would certainly learn is that Navajo and Zuni traditional religion, social/political structures, and values systems are no more similar than are those of traditional Buddhists and Presbyterians.”

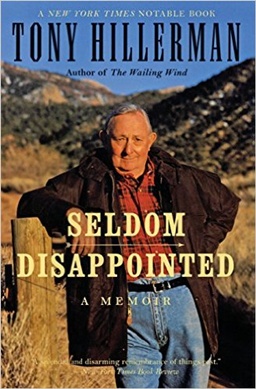

That’s from Seldom Disappointed: A Memoir, his excellent autobiography. And I think that’s one heck of an awesome answer.

I’m trying hard to make these posts as spoiler free as I can. But one element we learn early in Hillerman’s books are that people die and they’re not full of happy endings. The series isn’t ‘dark,’ but life and death on the reservation is often grim. That’s something we see in Dance Hall of the Dead and it gets reinforced quite often.

Cultural anthropology and archaeology are elements of the series. In Dance Hall of the Dead, a doctoral student named Isaacs is working a dig site for a revolutionary theory about Folsom Man. The first book I read in the series (and WELL out of order) was Thief of Time, which is about pot hunting.

With the significant role that religion plays for the various tribes that wander in and out of the stories, you’re going to learn a lot about the cultures of the Four Corners Region. For example, Navajos abandon a home if someone dies inside it: the evil spirit (chindi) of the person is in there. They try to move the person outside before death so the chindi can roam away.

The Great Taos Bank Robbery and other Indian Country Affairs is a collection of Hillerman non-fiction. “The Hunt for The Lost American” is an essay about Folsom Man.

The Great Taos Bank Robbery and other Indian Country Affairs is a collection of Hillerman non-fiction. “The Hunt for The Lost American” is an essay about Folsom Man.

Listening Woman is the third Leaphorn book and old Joe gets a few books off after this one as the younger Jim Chee takes center stage. I like the mystery in this one, and the scene in “the chimney” is as compelling as anything in the series.

Again, we learn of Leaphorn’s belief in the pattern of things: “Too much coincidence. Leaphorn didn’t believe in it. He believed nothing happened without cause. Everything intermeshed, from the mood of a man, to the flight of the corn beetle, to the music of the wind. It was the Navajo philosophy, this concept of interwoven harmony, and it was bred into Joe Leaphorn’s bones.”

Something that, to me, indicates Leaphorn was far from fully fleshed out in Hillerman’s mind: Leaphorn’s wife, Emma, is not mentioned in the first three books. We first encounter her in Skinwalkers, and discover they have been happily married to for thirty years. She plays a significant part in Leaphorn’s emotions for the rest of the series.

There’s something that pervades the early books and I think remains throughout the series (I’m on book seven of this re-read). Hillerman presents the dichotomy between the way white people think and Navajos think. It presents an obstacle that the Indian policemen must overcome to solve the crime.

A Navajo would never murder for gain. But that’s certainly a part of the mainstream culture. And Leaphorn and Chee have to consider this, even though it’s an alien concept to them and something they struggle to understand. Kind of a ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’ phenomenon, even though it’s usually their land.

The next post will talk about the first three Jim Chee books, so I’ll save something for that one. But last week, I included something about Tony Hillerman’s thoughts on outlining (not his thing). Today, I’ll add a bit about his first chapters.

FIRST CHAPTERS

When he started on novels, Hillerman would work to perfect that first chapter. He’d spend weeks, or even months, getting it just right before moving on to chapter two. But as he says in “Building Without Blueprints” (see last week’s post), “No matter how carefully you have the project planned, first chapters tend to demand rewriting. Things happen…Slow to catch on, I collected a manila folder full of perfect, polished, exactly right, per-shaped first chapters. Their only flaw is that they don’t fit the book I finally wrote. The only book they will ever fit will be one titled Perfect First Chapters, which would be hard to sell.”

Or as he says in Talking Mysteries (an insightful interview book with Ernie Bulow), “The First Chapter Law is, don’t spend much time on it. You’re going to have to rewrite it.” He says these first chapters are useless unless he can find a magazine willing to publish a series called, “First Chapters Abandoned When Their Books Divorced Them.”

He’s made other humorous observations about those first chapters. So, we’ve learned that Hillerman doesn’t find outlining helpful and he doesn’t spend a lot of time polishing the first chapter before moving on.

People of Darkness, the fourth book in the series, is quite a change. Tune in next Monday as we shift our attention to officer Jim Chee. Same Black Gate time, same Black Gate channel.

Part One – Meet Tony Hillerman

Part Two – The Navajo Sherlock Holmes

Part Three – Enter Jim Chee

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

His “The Adventure of the Parson’s Son” is included in the largest collection of new Sherlock Holmes stories ever published. Suprisingly, they even let him back in for Volume IV!

I’ve had a lot of fun with Hillerman’s Leaphorn series. They are like getting two stories for the price of one. One story is a mystery and another is a segment of Navajo life.

Ape – Yeah. I saw a FB comment about last week’s post that said they were pedestrian mysteries after you took away the Indian stuff.

Now, I don’t agree with that. But that’s like saying, “There’s nothing much to those Holmes stories after you take away the eccentricities and the brilliant deductions”…

[…] UPDATE – Post two, focusing mostly on Leaphorn, is live and you can read it here. […]

Thanks for this and for last week’s post. I enjoy Hillerman’s work immensely and agree with Wild Ape that you’re getting 2 stories for the price of one.

I’m also a big fan of Arthur Upfield. I hope you’re planning to give us something on his work in the future.

I was only marginally aware of Mr. Hillerman’s mysteries until A Thief of Time, the 8th Navajo Police book, exploded all over the bestseller lists. Well, better late than never!

Also, was Joe Leaphorn in Germany in 1945, on the ground? (See paragraph 2.) I mean, metaphorically, I suppose he was. And does that mean that Mr. Hillerman saw more of himself in Lt. Leaphorn than in Officer Chee?

Eugene – Fixed. Thanks!

Thief of Time was my first one as well. Hillerman talks about the publisher making it his ‘breakout book,’ which is a reason it was a bigger hit than the prior ones.