How to Worldbuild a Good Sandbox: Four Rules from the Warhammer 40K Universe

I’m working on a sandbox Space Opera setting.

Sandbox is the tricky part; a “sandbox” is a storyworld that lets you tell (or experience — if you are a gamer) all sorts of different kinds of story. Essentially, I’m building my Discworld.

Oh, you say, just make it big with lots of different kinds of settings plus spare blank spots on the map.

Yes, that gives you lots of flexibility (though less than you’d think). However, the stories won’t be — sorry, I can’t think of a better word — branded.

I mean, the asteroid miners over here and the fight against the dark lord over there, don’t need to belong in the same universe and the reader (or player) won’t really feel as if they are revisiting the same place.

So a good sandbox is one that maximises the possible range of branded stories.

Spend time with a 12-year-old tabletop gamer and you quickly realize that — in this light — Games Workshop’s Warhammer 40K universe is one of the best sandboxes around. You can could dump just about any Space Opera SF story into it, and it would still feel like 40K. To do Firefly, just plug in Orcs, Inquisitors and Space Marines and Imperial Guards. To do Starship Troopers tell a story about the Imperial Guard. To do Star Trek, just follow a Tau captain on their five year mission.

Less so in the Star Wars universe.

Firefly Wars would need a local civil war as backstory, since the cleanup after the prequels feels like it would involve more mass graves. Your Alliance could be the Empire, but the Empire doesn’t really feel as if it would do dark secrets — why bother hiding them? — or have secret super soldier programs– it has Stormtroopers and Sith anyway. Starship Troopers could be about the latter-day Stormtroopers, but the moral ambiguity would be lost. Star Trek…? No, not without taking a ship to a different galaxy and then it would not feel like Star Wars. It would lose its brand.

So the 40K ‘verse is a far better sandbox than the Star Wars one. How can this be? It appears to follow four basic rules…

The first pair of rules deal with the awkward problem that what you invent now will constrain what you can later invent…

1. Write Your History One Order of Magnitude Greater than any Side-Story You Might Want to Tell

- Your biggest historical events cap what you can later add.

In Star Wars, you can’t add another Battle of Hoth sized event, or another Death Star to the existing timeline…

By the way while Luke was plying his photon torpedoes,

a hundred light years away, General Flix Flenna was

winning a pivotal battle for a planet which would

determine the success or failure of the Rebellion…

No. Doesn’t work.

Nor can you add another campaign to WWII, nor an extra crusade to the Crusades. Feel free to invent a battle over a French provincial town, and a castle siege, respectively. While you are at it, add a skirmish to Waterloo 1815, but not a major cavalry charge.

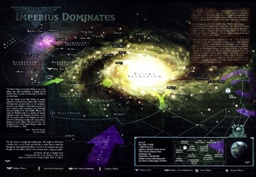

40K creates maximum flexibility by laying out histories spanning thousands of years, encompassing wars over entire galactic regions. There are established battles, but they are either moments in particular sagas, or mind-blowing finales to the big picture stuff.

Don’t detail the long war between the (Space) Elves and the (Space) Dwarves. Do note that they had a war, and describe its epic conclusion (which will cast a long shadow).

2. Don’t Leave Blanks Beyond Borders

- Established regions constrict the possibilities of undefined neighbouring ones

This one surprised me — I always thought it was a good idea to preserve some blanks for later!

The main reason is that regions interact and form each other. For example, if 14th century Scotland is a given, then you need a mercantile Low Countries with weavers, because otherwise there would be fewer Scottish sheep, and because you are going to meet merchants who trade there. Also, you can’t later specify a Steampunk Dystopian Atlantis just beyond Ireland, because otherwise the Scottish politics and military would be different, and characters would have different back stories.

It follows that you are better locking in the cool ideas at the start!

It’s also worth establishing more than one hostile culture, because adding them later will probably break the branding… or else look cut and paste.

The Star Wars galaxy has been mapped at various times, but it has the feeling of having been created by accretion. Nobody thought to add some big bads brooding on the edges. Alas, once you have disposed of the Empire, there’s nobody left to fight! You either have to put in extra-galactic bugs — like in the books — or else reboot the Empire. The shape of the Republic/Empire just doesn’t point to lurking Daleks or Space Orcs, and nobody worries about which side the Border Guard will come in on, or whether taking out the Death Star will trigger a Cyberman invasion. For this reason, you can’t just announce, “Oh by the way, the Borg live over here!”

The 40K galaxy is very thoroughly mapped, but unlike Star Wars, it’s full of warring super-cultures. You will never run out of adversaries.

Don’t mark a region “terra incognita.” Do mark it, “Warring cattle tribes.”

The other pair rules are about ensuring you can tell lots of different kinds of stories, and still have them branded.

3. Paint Your Factions With Plenty of Grey (Even if it’s Really Made Up of Black and White Points)

- Branded stories can only be as morally complex as the political setting.

In Star Wars, the Empire is evil. Good people are either for it or against it. Those who come to some sort of an accommodation are traitors, even if they have a good excuse. The same goes for the Nazis in WWII. That makes a fine adventure story but doesn’t offer much range. Similarly, it’s hard to present sympathetic Imperials or SS Officers intent just on “bringing order and dealing with the bandit problem”.

In contrast, the 40K universe presents you with a choice of factions, all bad when experienced from the wrong angle — e.g. under a Space Marine’s boot — all good –or the lesser of the available evils, at least — when they are defending you. Within each faction there are good guys and bad guys, and long-running internal disputes.

Don’t build a world of Dark Lords and Chosen Ones. Do muddy the moral waters sufficiently that most factions can accommodate good and bad people.

4. Make Your Most Significant Conflict Thematic

- The most significant conflict tends to define the brand.

Thematic conflicts are all about “big forces at work” rather than specific forces, e.g. “Good versus Evil” rather than “Rebels versus Empire.” They have the advantage that they can manifest from the epic, through the picaresque, down to the domestic.

For example: A farm boy who wants to see the wider universe. You could do that in a Dumarest novel, since they are pretty much “Urge to Travel versus The Forces that Tie Us Down.” However, if you want to do it in the Star Wars universe, then you need Stormtroopers to come for his droids.

40K doesn’t do domestic very well either, however its theme — “There is only war” — gives us a thematic conflict of “Everybody vs Everybody” meaning we can do Space Marines, who operate in a complex political context with inter-service and inter legion rivalries, rampaging Inquisitors and ambitious underlings, and also merchants trying to navigate the same and make a killing without being killed.

A similar “Everybody vs Everybody” thematic conflict in the The Expanse not only generates street violence, but also gives a political dimension to the criminal underworld. Even a bar brawl feels like an Expanse bar brawl.

Don’t set the Monolithic Dark Empire against the Surprisingly Liberal Republic of Tree Huggers. Do have soldiers beset by warring bureaucrats attempt to quell a civil war while clans of smugglers pursue a blood feud, all played out as part of a large class struggle between the Haves and the Have Nots.

Ultimately, it’s all about building in the right kind and scope of conflict and not limiting yourself out of the box by aiming too low, or too high.

If you’re in or near Edinburgh, Scotland this weekend you can find me at the awesome Conpulsion tabletop convention and we can talk about all this over a beer. You could even attend my writing workshop.

M Harold Page is the sword-wielding author of works such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”). For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

For the first time ever, I can see the appeal of Warhammer. A theme like “There is only war” would ordinarily not do much for me — it feels like an essential falsehood, therefore an excuse for various pernicious things. “Always” I could allow for, though I disagree, but “only,” not so much.

Warhammer’s other virtues, as you lay them out, are pretty significant.

The lesson here is: Game worldbuilding is different from fiction worldbuilding. This is something that many gamemasters don’t fully grasp at first.

The reverse is also true. Your experience with worldbuilding for a game doesn’t directly translate into skills for fiction worldbuilding.

The requirements for the background and the dynamics how things will turn out in practice are quite different.

I suppose making the borders bigger than your story makes people imagine what else is in the universe. This was an enjoyable post.

@Sarah—you should try some table top gaming. There is a faction called the Sisters of Battle. I’d love to see you commanding a force of those battle hardened ladies against the Tyranids or an orc Waaauughh! Harold is right, gaming with your 12 year old son will change your life.

@Martin Kallies

I disagree. I think that gaming has more leeway than fiction – it doesn’t matter if you lose the branding as long as you don’t lose the PCs. What makes 40K impressive is that it works for different kinds of fiction.

What I always loved about the old Warhammer world was that it was built in exactly this way. There were the big battles and other dramatic things going on, but most of the actual stories were very small scale adventures, covering a small number of people in a restricted area.

Some of my favourite characters are simply the ones trying to live their lives and be normal when either they or the circumstances the are in are fundamentally not.

See Genevieve from Kim Newman’s excellent Anno Dracula series as a great example.