How and Why You Should Withhold Information from the Reader

You’re not supposed to withhold information known to a point-of-view character. Or to put it another way around:

If the viewpoint character knows something relevant, then by default share it with the reader.

Except that successful authors do this all the time!

It’s most common in thrillers where we follow the Bad Guys, but don’t find out who they are working for until the end. However, you also find it in SF&F. For example, Scott Westerfeld’s marvelous The Risen Empire quickly turns out to be about a secret. We see one team try to expose the secret and another — who know what it is — ruthlessly try to preserve it.

At this point, people will nod their heads and trot out the wisdom they’re supposed to trot out: Once you know the rules, then you can break them; go serve your apprenticeship.

However, that’s not very helpful if — for example — the story you are trying to write hinges on a big secret.

I think there’s quite a different set of rules at work. As you might guess, as far as I’m concerned, it’s all about the conflict.

It always is about the conflict.

That’s where stories come from: “When Mr and Mrs Theme hate each other very much they produce a Plot…”

And readers only really see things that are part of an interesting conflict: essentially players, bones of contention, and arenas.

If you force something to prominence that’s not part of a conflict, then readers either ignore it or become irritated. For example, if you tell a war story and studiously avoid telling us that the heroes are in a Sherman Firefly, even though ALL the characters in the story know this — perhaps you want a surprise ending ? — then the reader has every right to be annoyed; you’ve created a secret that’s not really part of the conflict. You’ve also drawn attention to yourself as author, thus breaking the fourth wall. Naughty!

When a secret is part of the conflict, specifically the thing people are fighting over — as in The Risen Empire — then it makes good sense to keep it from the reader while at the same time showing the in-the-know antagonist point-of-view.

For example, the secret could be the true nature of an alien artefact. The good guys want to find out what it does, the Men in Black know what it is but don’t want to share. The precise nature of the secret doesn’t affect the car chases and shootouts so the story works.

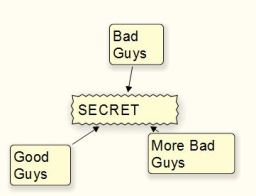

Ah, but what if the secret is the true nature of a shadowy organisation which itself is a player in the conflict?

You can show people taking orders from the secret, but the secret itself can’t have an onscreen story… or at least it can’t without you resorting to coy and irritating circumlocutions that at best turn your novel into a puzzle.

So the real rule is:

You can keep a secret from the readers as long as it is the bone of contention in a conflict and has no onscreen agency.

M Harold Page is the sword-wielding author of works such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”). For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)