Classically Awful or Awfully Classic: A.E. Van Vogt’s The World of Null-A

Alfred Elton van Vogt (1912-2000) is one of the great names of 20th century science fiction, and not just because the moniker sounds so odd, like it belongs to a mad scientist in a lurid Gernsbackian tale, the kind where “cosmic rays” are used to mutate the sleepy denizens of the city zoo into panicky prehistoric behemoths, which then rampage through the streets, spreading riot and chaos, thus allowing a cabal of sinister foreigners to hijack the metropolis’s secret supply of plutonium in order to build a colossal… sorry. Got a bit carried away there; once you’re in full Pulp Mode it’s hard to disengage. Back to A.E. van Vogt.

Alfred Elton van Vogt (1912-2000) is one of the great names of 20th century science fiction, and not just because the moniker sounds so odd, like it belongs to a mad scientist in a lurid Gernsbackian tale, the kind where “cosmic rays” are used to mutate the sleepy denizens of the city zoo into panicky prehistoric behemoths, which then rampage through the streets, spreading riot and chaos, thus allowing a cabal of sinister foreigners to hijack the metropolis’s secret supply of plutonium in order to build a colossal… sorry. Got a bit carried away there; once you’re in full Pulp Mode it’s hard to disengage. Back to A.E. van Vogt.

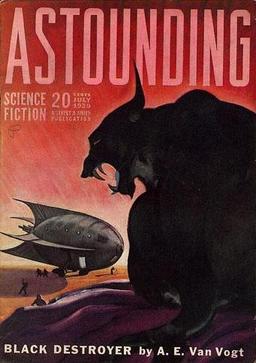

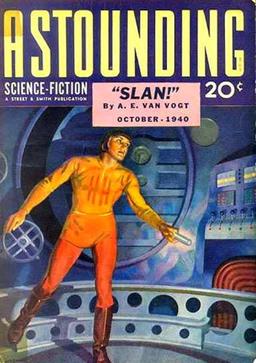

Van Vogt was a giant of the golden age of the 40’s, first appearing in John Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction with the short story “Black Destroyer” in 1939. In the years that followed, he dominated the pages of the magazine with countless short stories and novels that even today are regarded as classics, among which the best known are Slan, The Empire of the Atom, The Voyage of the Space Beagle, The War Against the Rull, The Book of Ptath, and The Weapon Shops of Isher. (He frequently incorporated his short stories into his full length books; van Vogt was a pioneer of the “fix-up” — a term he coined — in which a novel is cobbled together from earlier, shorter pieces.)

In an era in which many of the SF writers of the 40’s and 50’s (some of major importance) have vanished from the shelves, most of the van Vogt books I’ve mentioned are still in print, and he remains influential — and controversial. (He did a short stint as a cheerleader for L. Ron Hubbard’s dianetics, for instance.) His writing seems to be equal parts sublime and appalling, and any discussion of van Vogt must sooner or later get around to addressing one simple question: can a “classic” be a godawful, incoherent mess?

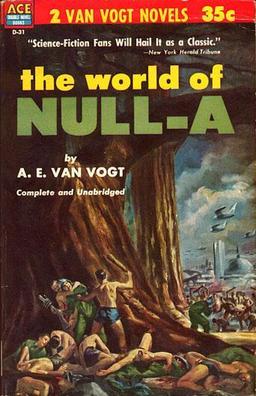

The van Vogt book best qualified to answer that question is The World of Null-A, after Slan probably his most famous — or infamous — work. The novel was serialized in Astounding in 1945 and published in hardback in a revised form in 1948. Van Vogt further revised it in 1970. The revisions were prompted by a superb and hilarious bit of demolition called “Cosmic Jerrybuilder” in which SF critic and writer Damon Knight painstakingly detailed every irrelevance, contradiction, and nonsensical dead end in van Vogt’s magazine version of the story. When you read The World of Null-A in its 1970 incarnation — the only one available now — take a moment and consider that you’re reading the cleaned up, straightened out version. It didn’t make nearly as much sense before. Oh my!

In the year 2650, in the City of the Machine, Gilbert Gosseyn (pronounced go-sane) finds himself at the center of a sinister plot by a galactic empire to take over the solar system. He discovers that his memories are false and that he doesn’t really know who he is; he’s manipulated by shadowy groups of opposing people whose motives he can’t fathom; he dies and reawakens in a new body; he discovers that he has a “second brain” but can’t figure out how to use it (he’s not so hot with brain number one either); throughout the story he periodically and unexpectedly teleports to Venus and back again like some sort of cosmic ping pong ball; he suddenly develops powers of telepathy and telekinesis…and when he finally understands his role in this vast galactic chess game (in literally the very last line of the book), the long yearned-for explanation turns out to be as nutty and incoherent as the rest of the story.

In the year 2650, in the City of the Machine, Gilbert Gosseyn (pronounced go-sane) finds himself at the center of a sinister plot by a galactic empire to take over the solar system. He discovers that his memories are false and that he doesn’t really know who he is; he’s manipulated by shadowy groups of opposing people whose motives he can’t fathom; he dies and reawakens in a new body; he discovers that he has a “second brain” but can’t figure out how to use it (he’s not so hot with brain number one either); throughout the story he periodically and unexpectedly teleports to Venus and back again like some sort of cosmic ping pong ball; he suddenly develops powers of telepathy and telekinesis…and when he finally understands his role in this vast galactic chess game (in literally the very last line of the book), the long yearned-for explanation turns out to be as nutty and incoherent as the rest of the story.

Van Vogt was famous for his convoluted tales of paranoid conspiracies and latent supermen, but The World of Null-A is in a class by itself; it’s legendary for its incomprehensibility, and it more than lives up to that reputation. Neither Gosseyn nor the reader has the slightest idea what is going on at any time, and apparently neither does van Vogt. The reader’s disorientation is exacerbated by the sheer speed with which one inexplicable event follows another; you don’t have time to scratch your head (or bang it against the table) because you’re turning the pages so fast. It’s gobbledygook at 120 miles per hour.

The World of Null-A is what would have resulted if Jackson Pollack had given up painting and turned his unique methods to the task of writing a science fiction novel, and it’s a good thing he didn’t. Paint can be (seemingly) randomly spattered across a canvass and the end result can still be pleasing; if you do the same thing with words on a page, the effect is not conducive to smooth reading, to say the least; it’s not conducive to much of anything.

Page after page of The World of Null-A is nothing but undigested, indigestible chunks of raw idea; nothing has been blended, integrated, or often even minimally connected; it’s all lumps and no gravy. The characters are flat, the pacing is wildly uneven, the prose is workmanlike at best but more often seems the hasty, sullen product of someone compelled to learn the English language at gunpoint. (The “Null-A” part, by the way, means “non-Aristotelian.” Thus the far-future world of the novel does not operate by the rigid, syllogistic logic followed by, say, the buyers of pulp science fiction magazines and their parents and teachers circa 1945. “When I say take out the trash, young man, I mean take out the trash!” Who wouldn’t want to escape from the stifling shackles of a world like that?)

Even with all that, the damn thing is so loony it’s kind of fun to read as long as you give up any notion of its making sense and just go along for the ride. (It helps to think of the book as a fireworks show instead of a mural.) Plus, I have a soft spot (maybe in my head) for someone who can write the following:

Even with all that, the damn thing is so loony it’s kind of fun to read as long as you give up any notion of its making sense and just go along for the ride. (It helps to think of the book as a fireworks show instead of a mural.) Plus, I have a soft spot (maybe in my head) for someone who can write the following:

“You gave me a start,” she said. But her voice was calm and unstartled, properly subdued. She had suave thalamic reactions, that girl.

So, by just about any standard literary measure, The World of Null-A is a train wreck, the very antithesis of a classic. Setting aside the thumb-fingered pulp prose, which is something you often simply have to accept in tales of this vintage, the story itself just doesn’t work; nothing fits together, nothing makes any sense. It’s a rollercoaster ride to nowhere. Thus the case for the prosecution.

But wait a minute – what if all the confusion and incoherence and disjointedness isn’t a bug — what if it’s a feature? Van Vogt has been an influential writer over the years, and he influenced no one more than that darling of the mainstream literary intelligentsia (now that he’s dead), Philip K. Dick. Dick said this of his master:

I started reading SF when I was about twelve and I read all I could, so any author who was writing about that time, I read. But there’s no doubt who got me off originally and that was A.E. van Vogt. There was in van Vogt’s writing a mysterious quality, and this was especially true in The World of Null-A. All the parts of that book did not add up; all the ingredients did not make a coherency. Now some people are put off by that. They think that’s sloppy and wrong, but the thing that fascinated me so much was that this resembled reality more than anybody else’s writing inside or outside science fiction.

Certainly one of the strongest arguments against the “well-made story”, in science fiction or any other genre, with all loose ends neatly tied, all t’s crossed and i’s dotted, is that that vision of life is sheer fantasy, nonsensical and unbelievable, farther removed from reality than the most extravagant fairy tale. That’s not how the world really works, and a passion for neatness and order and sound construction is one way we blot out our fear of the chaos that we know is lurking just beneath the surface of every day. We’re uncomfortable with that knowledge, in fiction just as much as in life, and credit is due to those who refuse to abide by the safe conventions of neatness and normality. Those conventions are a dodge that we employ to avoid looking the truth in the face.

Dick pointed this out when he countered Damon Knight’s criticisms:

Damon feels that it’s bad artistry when you build those funky universes where people fall through the floor. It’s like he’s viewing a story the way a building inspector would when he’s building your house. But reality really is a mess, and yet it’s exciting. The basic thing is, how frightened are you of chaos? And how happy are you with order? Van Vogt influenced me so much because he made me appreciate a mysterious chaotic quality in the universe which is not to be feared.

We enjoy stories where everything nicely resolves before the final, tasteful fadeout, where we can see and understand how all the pieces neatly fit together. These kinds of stories are undeniably comfortable; they’re reassuring, and often useful too, as we try to make a map to navigate our way through the daily maze.

But as A.E. van Vogt and Philip K. Dick knew, the picture painted by this kind of structured tale might be calming and it might even be useful, but it certainly isn’t true; much as it discomforts us to admit, it doesn’t accord with our experience of life as it is actually lived, where “people fall through the floor” all the time.

Of course, all stories are lies of a sort, the ones about tucking the kids in after dinner just as much as the ones about waking up on Venus in a new body. But if art is, as has been said, a lie that tells the truth, then we must reckon that there is a surprising amount of truth hiding in the headlong, sloppy, surreal dreams of Alfred Elton van Vogt. Just enough, perhaps, to make the attachment of the term “classic” to his books (even The World of Null-A) reasonably rational… or at least not quite nutty enough to feature in one of his own stories.

Thomas Parker’s last article for Black Gate was Beyond the Immediate Shiver: The Rim of Morning by William Sloane.

I’ve read very little Van Vogt — only one I’m sure of is Book of Ptath, and that was 25 years ago so I remember nothing. Have a big ol’ mess of them on my shelf, though.

And I had no idea he lived until 2000.

Just wanted to toss in that van Vogt was a major Solar Pons fan and you can find and essay he wrote about him on page 18.

http://www.solarpons.com/Gazette_2007_1.pdf

My take, for what it’s worth, is here: https://www.sff.net/people/richard.horton/aced76.htm

Bottom line — I agree pretty fully with Thomas’ take here.

Interesting take on van Vogt and the chaotic nature of Reality. Still, I would say that his fiction did not embrace the chaos as did Phil Dick’s writing, but embodied it in an impossible attempt to control it. Since it cannot be controlled, that friction in his fiction is what does attract and repel us.

I especially like that quote from the New York Herald Tribune on the Ace double edition: “Science-Fiction Fans Will Hail It as a Classic.” Translation: “Those Idiots Will Swallow Anything.”

The Mill On The Floss is also considered a “classic”, but would you read it? Nope.

I think Isher is his most readable and enjoyable, but it’s still not great. Yes, a classic can be a mess, or boring, or WTF. There are better choices for reading Golden Age authors.

Watch it now – I revere George Eliot. Though I haven’t read the Mill on the Floss, I have read Middlemarch – twice. (Which is not something I’ll ever be able to say about The World of Null-A…)

Goodness sakes, I certainly plan to read THE MILL ON THE FLOSS someday … or at least MIDDLEMARCH.

Eliot wrote a pretty good novella with fantastical aspects, THE LIFTED VEIL, by the way. Just to bring her on topic!

What can I say? I am and have always been an adorer of A. E. van Vogt’s writing. I’ve read the Null-A books too many times to count. They’re almost like poetry to me. FWIW, I’ve written a bit about it, if anyone is interested:

http://www.raphordo.blogspot.com/2013/02/a-e-van-vogt.html

http://www.raphordo.blogspot.com/2015/07/two-hundred-million-ad.html

In a nutshell: Yes, his style is quite awful at times. Yes, his plots are weirdly and wildly incoherent. Yes, his supermen are bafflingly stupid, naïve, and weirdly immature. But still. His better novels are so filled with stunning settings, amazing ideas, and universe-shaking revelations, each of which could have been the basis for an entire novel in the hands of a more polished writer, that I find myself able to forgive him his little eccentricities.

Maybe his writing is not all that great. Maybe it’s actually quite bad. Granted. His later fix-ups are horrendous by all accounts. But I like the convolution this technique imparts to his earlier, more coherent novels; reading them sends me off on so many wild tangents that I find them supremely entertaining again and again. And, as a mathematician with humanistic leanings, I appreciate his disinterest in technology, and derive intellectual enjoyment from his exploration of ideas like the transformative value of modern logic (Null-A) and scientific integration (Nexialism). I’d rather read him than any other Golden Age writer.

Funnily enough, I was wondering if Dick had read Vogt’s stuff just before you said he did. And Dick’s interpretation of Vogt is reflected in his work, and in a positive sense, too.* I can think of a couple of random examples, but a good one is the scene in ‘Through a Scanner Darkly’, when the mc is observing his girlfriend via close-circuit TV and her face changes. He rewinds and watches – and the same thing happens again. No explanation is every forthcoming, but the image is a haunting one nonetheless, maybe because it ties in with Dick’s gnostic ideas about reality.

* I mean, as opposed to being an excuse for sloppy plotting.

I don’t want to give the impression that I’m a van Vogt basher – I’ve very much enjoyed The Book of Ptath, The Empire of the Atom, and especially Slan, which I think is his best book. But if you’re going to read him, you certainly have to be ready to make some allowances, perhaps even to a greater extent than you do for other writers of his era. Van Vogt has always had his partisans – for every Damon Knight, there’s a Brian Aldiss, who called his tales “hard SF dreams” and praised the power and resonance of their surreal, hallucinatory logic. And Aonghus, the PKD novel that makes me think most of van Vogt is UBIK – it would be interesting to do a close comparison of that one and Null-A.

Thanks for this! A great review, and really interesting stuff about PKD’s reaction against the Futurian party line on Van Vogt. One can see the influence AEV must have had on PKD.

I have mixed feeling about Van Vogt. I tend to like him when he’s wildly throwing out stuff. When he tries to bring it all together (as with the novel versions of THE WEAPON SHOPS OF ISHER and VOYAGE OF THE SPACE BEAGLE), I don’t like it as much: the original stories were better. But PTATH is good, rereadably good, and so are a lot of his short stories. Maybe you’re nerving me up to have another look at those Null-A books.

I actually learned about Van from the interview that you reference here of PKD. Dick’s description of van Vogt’s inconsistencies as “real life” made me rewind the interview a bit to get the author’s name. I started with Slan, which I found to be slightly chaotic in its own right. Van has this way of jumping ahead to the next key moment by just glancing over larger time periods within the same chapter (i.e. “Two day later…” or “It only took a year…”), and suddenly you’re there with no description of how the character specifically arrived. Is Van showing faith in the reader, allowing the imagination to fill in the blank, or is he just lazily employing the suspension of disbelief maxim? I think I rather enjoy believing the former. Interestingly enough, while helping to introduce a philosophical concept like Null-A that hinges on thought through all shades, Van certainly seems to attract a very black and white opinion of his writing from readers.

After reading Slan, and feeling that maybe I had missed some things that may have given me a deeper understanding of events and themes, I chose to listen to The World of Null-A read as an audiobook before reading it manually. It was a HUGE help. In the end, I was able to follow the fast pace of Van’s quickly changing landscape because I already had a map of sorts. Fortunately, I held off from listening to the third act, so the payoff of was fulfilling. I didn’t guess the end, but only because I didn’t try. Where’s the fun in that?