Sarah, William Morris, and Me

Hurry, hurry, hurry! Step right up, you whippersnappers, and see Old Fogy’s Carnival of Cantankerous Complaints. Present your tickets and take your seats for yet another unsolicited argument justifying my personal preference for bound paper books over electronic texts. Keep your arms and hands inside the diatribe at all times. (Go away kid, you bother me.) Ready?

Hurry, hurry, hurry! Step right up, you whippersnappers, and see Old Fogy’s Carnival of Cantankerous Complaints. Present your tickets and take your seats for yet another unsolicited argument justifying my personal preference for bound paper books over electronic texts. Keep your arms and hands inside the diatribe at all times. (Go away kid, you bother me.) Ready?

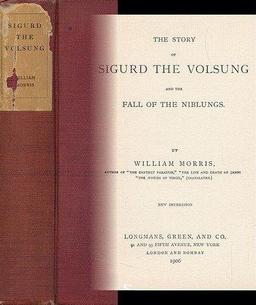

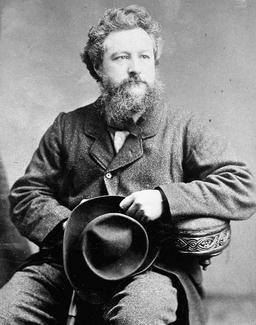

A while back I decided I wanted to read William Morris’s 1877 book-length epic poem, Sigurd the Volsung, a violent Victorianizing of old Norse myth. After discovering that the paperback copy I ordered from Amazon was heavily abridged (grrrr!) I located an old used copy online — an American edition published in Boston by Roberts Brothers in 1891. (Morris was a popular author, and editions of his works that are this old are not at all scarce; I think it cost me ten or fifteen dollars.)

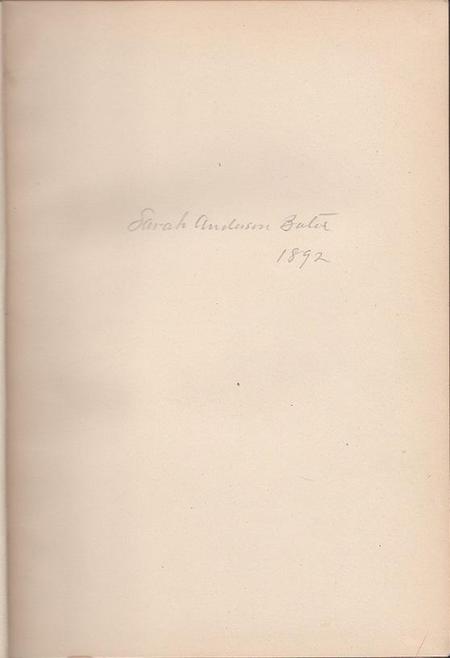

When the book arrived, I carefully took it out of the shipping package (books of this vintage are wonderfully heavy) and opened the dark green cover to look through it. I immediately saw, on the very first blank page, a name and a date neatly written in pencil:

Sarah Anderson Bates 1892

I’m not specifically a collector of signed editions, though I have acquired quite a few over the years (mostly from science fiction writers), among them books signed by Ray Bradbury, Frank Herbert, Ramsey Campbell, Michael Shea, Harlan Ellison, Peter Beagle, Fritz Leiber, and Cormac McCarthy — some pretty heavy hitters.

The signature I value most is Sarah Anderson Bates. Why? Partially for the surprise of having it at all, but mostly because she is someone I know nothing about, who was — just like me — an ordinary person who had a book she valued, and who, by writing her name in it, became a kind of time traveler, sending a signal to me, a person who probably wasn’t even born until long after she was gone.

Sometimes I like to look at her signature and try to use it to imagine what she was like. I think she was fairly young in 1892, or at least not yet old, because her name is written in a firm, strong hand with no trace of a waver, and reading whopping big books of narrative poetry is something that is most often essayed by the young.

I think she was an unaffected, no-nonsense person; her signature is strong and straightforward, with no elaboration or decoration, and no (what would be taken in her day to be especially “feminine”) loops or curlicues are anywhere to be seen. Did she work? Was she a nurse? A teacher? A librarian?

I think one of those last two is likely, not only because they were among the few professions open to a woman of that time, but also because her possession of this book suggests that she had literary tastes and aspirations, and her liking for the elaborate poetry of Morris makes me think that she may have had more than the average education that a woman of her day would have received – perhaps she was a graduate of the kind of “Woman’s College” that dotted New England in that era. (I believe Roberts Brothers was a regional firm rather than a national one, so Sarah probably lived in Boston or somewhere close by in Massachusetts.)

Additionally, I think she bought this book for herself rather than receiving it as a gift, as there is no “To Sarah from Uncle So and So” inscription or anything like it, only her own name apparently written in her own hand. Her buying the book for herself also reinforces my view of her as an educated, professional woman, and makes me think that she had an independent streak; I only hope it didn’t cause her too much trouble, especially as I believe she was also intellectually adventurous. After all, she bought a book that was full of pagan mystery and thunder, and was filled with blood and fire, violence and romance. I can only hope that someone in her family heartily disapproved of her reading such things!

When Sarah went to the bookstore, she likely arrived and departed via a horsedrawn streetcar or carriage, and took her book home to read by gaslight. Whatever her station in life, her days were occupied with the kind of repetitious, menial tasks that we have long since left behind; from rising to retiring she wore the kind of clothes that, when we look at them in old photographs, we gasp and say, “Oh my God! How could they have worn things like that?! In the summer — with no air conditioning!” and she almost certainly spent many hours every week washing those heavy clothes by hand.

Of course, all of my Sherlockian detective work may be completely off the mark (as most of us are, I’m certainly a good deal closer to the fogbound Dr. Watson than I am to the Great Detective himself), but there is no doubt that whatever the specifics, Sarah Anderson Bates’ life was very different from mine, and that most of it is lost and irrecoverable now.

But there’s something I do know — we have held the very same book in our hands, Sarah and I. We have turned the very same pages, read the very same words. And perhaps it is not too much to believe that our hearts responded to the poet’s work in much the same way. Both of us sat alone in our individual rooms, communing with William Morris, himself far separated from us but signaling to the two of us, unseen across the miles and across the years.

I responded to his seductive cadences with hope, fear, joy, sadness, exaltation — did Sarah? I think she did; that’s why she bought the book, one hundred and twenty three years ago. As I read Morris’s account of the suicide of the bereaved Gudrun, maddened by the fading of the world she knew and the loss of everyone she loved, I was stirred to contemplate the inevitable passing of my own world and myself with it:

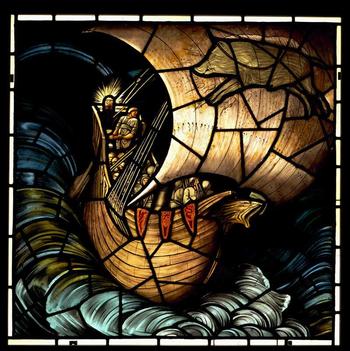

Then Gudrun girded her raiment, on the edge of the steep she stood,

She looked o’er the shoreless water, and cried out o’er the measureless flood.

“O Sea, I stand before thee; and I who was Sigurd’s wife!

By his brightness unforgotten I bid thee deliver my life.

From the deeds and the longing of days, and the lack I have won of the earth,

And the wrong amended by wrong, and the bitter wrong of my birth!”

She hath spread out her arms as she spake it, and away from the earth she leapt

And cut off her tide of returning; for the sea-waves over her swept,

And their will is her will henceforward; and who knoweth the deeps of the sea,

And the wealth of the bed of Gudrun, and the days that yet shall be?

As she read those words, did Sarah feel the same pleasurable melancholy, indulge in the same reverie of the transitoriness of life that I did when I read them more than a century later? I think so; I believe that Sarah, William, and I were all united in that moment.

As I read Sigurd the Volsung, I didn’t just feel close to the mind of William Morris. I felt that I was close to Sarah Anderson Bates, and that through this book (this scrap that remains of her life) she had entrusted her feelings — herself — to me, until it is my turn to join her in the lost and irrecoverable.

My 1891 Roberts Brothers edition of Sigurd the Volsung is big and heavy and unwieldy, not in any way made for convenience or portability. It is not a flexible, multimedia platform suited for the fast-paced twenty first century. What it is is a lifeline, one that reaches back to a person I really know nothing about but who is now a part of my life, and that reaches forward to a place that I will never see. It connects me with both of them.

I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Thomas Parker’s last article for us was Building a World in a Vacant Lot: The Circus of Dr. Lao.

If Sarah were able to afford the purchase of the book that is now yours, there’s a pretty good chance that she didn’t have to wash her own clothes. But yes! one does wonder about the people who have owned one’s old books. My oldest book is the first (of two volumes) of the Memoirs of Samuel Foote, Esq., with a Collection of His Genuine Bon-Mots, Anecdotes, Opinions,&c, Mostly Original. And Three of His Dramatic Pieces Not Published in His Works. Philadelphia: S. F. Bradford, 1807.

This was given to me and I keep it as a book to show to students who won’t have seen books that old, showing how supple the paper still is, being, I suppose, rag-based rather than wood pulp-based, etc.

The book is signed on the front endpaper: E. B. Harrington, Roxbury; but the bookplate opposite says E. B. Harrington, San Francisco. “Not to be taken from the room!”

So what’s the story? Did Mr. Harrington open his personal library to use of some members of the public? The bookplate numbers the book as 122.

I’m left to wonder what the story is here, and how it was that it came eventually to the Seattle area, from whence, thanks to a friend, it came to me in rural North Dakota….

You’re probably right about the laundry, Major. It’s just wearing those heavy clothes that gets me, especially those high collars!

Real books are also treasuries for other kinds of communication from the past. Many years ago, I purchased a 2 volume set of the complete Robert Browning – blame Lin Carter’s “Dragons, Elves and Heroes” for my liking for this poet. Inside the book was the torn bottom half page of a letter. I have no idea who the writer was, gender, age, nationality. I would suspect it was a white British woman. One side of the letter reads as follows:

“carefully planned educational programmes instead of all these dreary sales of work and the like. The spent a whole evening reading Karshish by Browning while I was there which is not exactly light weight stuff. I wouldn’t have understood much of it if I hadn’t heard Janet Longman’s father”…

I found the letter nestled by Browning’s Karshish. However, never mind the mystery of Janet Longman’s father, it was the other side of the letter that really intrigued me:

“I think the nicest thing about Christmas is getting letters from friends.

This has been a shattering year for me. It didn’t get off to a very good start as I upset the peace of the home by becoming interested in Mormonism. Really, I had no idea what”…

And there it ends. The Browning was published in 1910 and I acquired it in the 70s. The letter has a feel of the 1920s of the leisurely upper and middle classes portrayed by Agatha Christie. I shall never know what the effect of Mormonism was on the writer’s family. I am just glad that the recipient thought that the author’s comment on Karshish was worth keeping.

I have a great deal of time for well done, properly scanned ebooks. But they don’t replace the pleasure of holding a book, properly bound with good paper. I shan’t be replacing my Browning with an ebook version. My Browning has a message from times past and that’s something an ebook will never deliver. Neil

Really interesting, and strangely moving.

Neil touched on something with his e-book comment. A book allows you, in a sense to time travel with other readers, as Thomas suggested earlier.

I’ll never forget holding a book that Harold Lamb had signed to his mother. I wondered how it had come to be in that used bookstore and then remembered that Lamb’s children had died without any children of their own, so that the work, and the moment he had signed and dedicated the book, were like bulwarks thrown up against a flood of history that had swept him and his family away.

Here’s a poem for ya:

Marginalia – Poem by Billy Collins

Sometimes the notes are ferocious,

skirmishes against the author

raging along the borders of every page

in tiny black script.

If I could just get my hands on you,

Kierkegaard, or Conor Cruise O’Brien,

they seem to say,

I would bolt the door and beat some logic into your head.

Other comments are more offhand, dismissive –

‘Nonsense.’ ‘Please! ‘ ‘HA! ! ‘ –

that kind of thing.

I remember once looking up from my reading,

my thumb as a bookmark,

trying to imagine what the person must look like

why wrote ‘Don’t be a ninny’

alongside a paragraph in The Life of Emily Dickinson.

Students are more modest

needing to leave only their splayed footprints

along the shore of the page.

One scrawls ‘Metaphor’ next to a stanza of Eliot’s.

Another notes the presence of ‘Irony’

fifty times outside the paragraphs of A Modest Proposal.

Or they are fans who cheer from the empty bleachers,

Hands cupped around their mouths.

‘Absolutely,’ they shout

to Duns Scotus and James Baldwin.

‘Yes.’ ‘Bull’s-eye.’ ‘My man! ‘

Check marks, asterisks, and exclamation points

rain down along the sidelines.

And if you have managed to graduate from college

without ever having written ‘Man vs. Nature’

in a margin, perhaps now

is the time to take one step forward.

We have all seized the white perimeter as our own

and reached for a pen if only to show

we did not just laze in an armchair turning pages;

we pressed a thought into the wayside,

planted an impression along the verge.

Even Irish monks in their cold scriptoria

jotted along the borders of the Gospels

brief asides about the pains of copying,

a bird singing near their window,

or the sunlight that illuminated their page-

anonymous men catching a ride into the future

on a vessel more lasting than themselves.

And you have not read Joshua Reynolds,

they say, until you have read him

enwreathed with Blake’s furious scribbling.

Yet the one I think of most often,

the one that dangles from me like a locket,

was written in the copy of Catcher in the Rye

I borrowed from the local library

one slow, hot summer.

I was just beginning high school then,

reading books on a davenport in my parents’ living room,

and I cannot tell you

how vastly my loneliness was deepened,

how poignant and amplified the world before me seemed,

when I found on one page

A few greasy looking smears

and next to them, written in soft pencil-

by a beautiful girl, I could tell,

whom I would never meet-

‘Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.’

To echo a few other comments, I have a thing about not removing the papers that I find in old books I’ve bought. Somehow I feel that I’m a curator rather than an owner, and that I don’t have the right to remove what someone else has seen fit to include.

My grandfather had the quaint habit of keeping newspaper clippings in related books; sometimes this forms a kind of commentary, or a record of his thoughts at the time. I have his 1897 copy of The Negro and the White Man, which was written by a former slave, for a white audience, as a plea for increased understanding and equality between the races. In the book I found a newspaper article (“Africa Motherland of Man, Anthropologist Leakey Says”) about paleontological research into human ancestry in Africa.

Inside the front cover the following is written: “Presented To: Nathaniel W. Oliver, Jr. By his father Rev. N. W. Oliver Pastor of the A.M.E. [African Methodist Episcopal] Church of Eufaula I.T. [Indian Territory] Dec 1897.” My grandfather, a Greek living in Oklahoma, must have found the book in a junk store, which he had a habit of visiting. An interesting artifact.

[…] Thomas Parker’s last article for us was Sarah, William Morris, and Me. […]