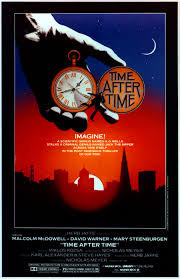

Adventure On Film: Time After Time

Movie fans will forever remember Malcolm McDowell for his simpering, ultra-violent turn in A Clockwork Orange (1971), but actors aren’t the sort to rest on their laurels, and by 1979, McDowell felt ready to embody a genuine historical figure, H.G. Wells.

Clockwork Orange (1971), but actors aren’t the sort to rest on their laurels, and by 1979, McDowell felt ready to embody a genuine historical figure, H.G. Wells.

The film was Time After Time, not to be confused with the Cyndi Lauper song (or the infinitely better cover by songbird Eva Cassidy), and if there’s a more definitive origin point for the Steampunk movement, I’d like to know what it is.

At the helm is first-time director Nicholas Meyer, who must have a soft spot for science fiction. Only a few years later, and armed with a much heftier budget, he was tapped to captain Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan (1982).

As for Time After Time, it’s far from perfect –– the script contains several gargantuan plot holes, and we viewers (if I may be forgiven the mixed metaphor) must swallow hard to keep up –– but it does work in fits and starts, thanks especially to the looming presence of David Warner as a time-skipping and dangerously prescient Jack the Ripper.

I’ll avoid significant spoilers, but the basics of the plot look like this: back in Victorian London, H.G. Wells invents a time machine; “Jack” steals it and heads to San Francisco, 1979; Wells follows, intent on bringing “Jack” back; along the way, Wells meets banker Amy Robbins (Mary Steenburgen, in her first starring role) and unwittingly makes her “Jack’s” next target.

I’ll avoid significant spoilers, but the basics of the plot look like this: back in Victorian London, H.G. Wells invents a time machine; “Jack” steals it and heads to San Francisco, 1979; Wells follows, intent on bringing “Jack” back; along the way, Wells meets banker Amy Robbins (Mary Steenburgen, in her first starring role) and unwittingly makes her “Jack’s” next target.

Lunacy, right?

To quote Sarah Palin, “You betcha.”

Much like Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986), which also plopped out-of-their-element time travelers into contemporary San Francisco (both films allow for a stroll through Golden Gate Park), Time After Time works best when it stays light on its feet. McDowell is badly miscast as Wells (he’s insufficiently eccentric to convince as Wells, and he’s too wide-eyed to be a useful foil for Warner’s Ripper), but he shows a flair for comedy, when given the rope to explore his new environs.

To make matters worse, director Meyer seems torn about what Time After Time is meant to be. Is it an essay about human nature, our innate violence? Or is it in easy-going diversion in which obvious targets such as McDonald’s and frenzied cabbies come in for their share of ribbing? Or –– third option –– is it a bloody, sci-fi chase film centered on a deranged serial killer?

Can it possibly be all three simultaneously?

Meyer, whose directorial hand in Khan felt assured and steady, is not in equal control here. To be sure, the script can be blamed for much of the trouble, but as it turns out, that’s Meyer, too: he’s the sole screenwriter, although the story credits lie elsewhere.

Meyer, whose directorial hand in Khan felt assured and steady, is not in equal control here. To be sure, the script can be blamed for much of the trouble, but as it turns out, that’s Meyer, too: he’s the sole screenwriter, although the story credits lie elsewhere.

Sadly, even behind the camera, Meyer seems lost. There is such a thing as “film language,” the sequential creation of images that, when cut together, tell a compelling, clear story. Past masters (and theorists) have included Sergei Eistenstein, Alfred Hitchcock, and Max Ophuls, and there are many working today of equal skill, which is hardly a surprise: cinema is a very new art form, one that is still developing, but much has been learned, tested, and established now as obvious best practices.

In Time After Time, what cinematic language there is feels as if it’s being spoken by a foreigner with a limited vocabulary. Only once does the film jar as it should (Warner pops suddenly into frame, from an unexpected direction, during a close-up of McDowell) and it repeatedly confuses screen direction and geography. Thrillers (if indeed that’s what this is) cannot afford to be so lax.

At least the chemistry between McDowell and Steenburgen is legit. Not long after the filming, the two thespians married.

At least the chemistry between McDowell and Steenburgen is legit. Not long after the filming, the two thespians married.

Time’s special effects are laughably bad, especially given the advent of films such as Star Wars and Close Encounters Of the Third Kind, both from 1977. By ‘79, the rainbow prisms that accompany the vanishing time machine would surely have struck theater goers as something straight out of low budget TV from 1964, and yet, inexplicably, one of my favorite film reference books, The Movie Guide by James Monaco, calls the effects “excellent.” Go figure.

A brace of further Star Trek tie-ins deserve mention. David Warner popped up not once but twice in the Trek film franchise, first in the why-did-they-make-that disaster known as Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989), and then in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991) as the Klingon ambassador.

(Warner also plays the Supreme Being in Time Bandits (1981) and itinerant preacher Josh in Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970), a role for which he will always be dear to my heart.)

(Warner also plays the Supreme Being in Time Bandits (1981) and itinerant preacher Josh in Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970), a role for which he will always be dear to my heart.)

Malcolm McDowell made his mark on the Trek franchise by portraying escape-minded scientist Soran in Star Trek: Generations (1994). You remember him: the white-haired, shock-cut twerp who had no business killing off the unbeatable Captain Kirk.

And yet, Soran (the little pipsqueak) managed what the combined Romulan and Klingon empires could not. I hate Soran for that, and I blame McDowell. Personally.

Vendettas aside, as a milestone in the evolution of fantasy’s on-screen life, and as one of several birth points for the steampunk phenomenon, Time After Time deserves attention. But, if what you’re after is a successful movie that works well on its own terms, I’m afraid one must look elsewhere. Or possibly elsewhen.

Vendettas aside, as a milestone in the evolution of fantasy’s on-screen life, and as one of several birth points for the steampunk phenomenon, Time After Time deserves attention. But, if what you’re after is a successful movie that works well on its own terms, I’m afraid one must look elsewhere. Or possibly elsewhen.

‘Til next time.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time, forthcoming in fall, 2014.

I never saw ‘Time After Time’ but I read the book, which I remember being pretty enjoyable.

Warner was also in an STTNG episode ‘Chain of Command’ as Picard’s interrogator – a sequence which borrowed heavily from Winston’s interrogation sequence in 1984. He was very good – he generally is.

Interestingly enough, I remember seeing an interview with McDowell in which he was asked how certain roles had impacted on his career. He cited his performance in ‘Star Trek’ as a case in point. He wasn’t a huge SF fan, the part was a pretty small one (in terms of how long it took to shoot) and so he was astonished by how much the role increased his visibility. I’m guessing because – at the time – he may not have been as well known in the US as the UK.

Aonghus, you’re absolutely right about STTNG. I’d forgotten about that one. Both Patrick Stewart and Warner were members of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and presumably had known each for years by the time they squared off under the Orwellian lamps.