The Dungeon Dozen

The first roleplaying game I owned was the 1977 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set edited by J. Eric Holmes, as you’re all probably tired of hearing by now. Among the many memorable features of that boxed set was that some of its printings (including my own) did not include dice. Instead, these sets included a sheet of laminated paper chits printed in groups that mimicked the ranges of polyhedral dice (1–4, 1–6, 1–8, 1–10, 1–12, and 1–20). The purchaser of the game was instructed to cut them apart and “place each different type in a small container (perhaps a small paper cup), and each time a number generation is called for, draw a chit at random from the appropriate container.”

The first roleplaying game I owned was the 1977 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set edited by J. Eric Holmes, as you’re all probably tired of hearing by now. Among the many memorable features of that boxed set was that some of its printings (including my own) did not include dice. Instead, these sets included a sheet of laminated paper chits printed in groups that mimicked the ranges of polyhedral dice (1–4, 1–6, 1–8, 1–10, 1–12, and 1–20). The purchaser of the game was instructed to cut them apart and “place each different type in a small container (perhaps a small paper cup), and each time a number generation is called for, draw a chit at random from the appropriate container.”

This I dutifully did, taking several small Dixie Cups from my upstairs bathroom for the purpose. Leaving aside the disbelief-suspending flower print of the cups, this method of random number generation was awkward and decidedly un-fun. Consequently, I set out to find a proper set of dice with which to play D&D, a quest that took me to a local toy store, which had them hidden away behind the counter. I bought that set – made of terrible, low impact plastic – and rushed home to use them. I wanted to be a “real” Dungeons & Dragons player. For all their faults, those dice were, in many ways, what sealed my fate as a lifelong roleplayer. There was something downright magical about those little, weirdly shaped objects that captured my imagination almost as much as the game itself.

I am fascinated not just by dice, but also by randomness. I’ve come to believe that one of the real, perhaps fundamental distinction between “old school” roleplaying games and their latter day descendants is the extent to which randomness informs game play. As a younger person, I went through a period when I intensely disliked randomness and used it as a bludgeon against games, including D&D, that I decided I disliked. Older, if not wiser, I no longer think that way. Indeed, I celebrate randomness as a vital part of what makes a RPG enjoyable for me. Randomness is frequently a godsend, providing me with a steady stream of ideas and inspiration when I find myself at a loss for either (which is often). Randomness also enables me to be surprised, even when I’m the referee, which is no small feat after more than three decades behind the screen. In short, I love randomness.

Therefore, I suppose I’m predisposed to love a book like The Dungeon Dozen by Jason Sholtis. This 222-page book is a compilation of the many “flavor-rich yet detail-free” random tables available on Sholtis’s eponymously named blog, accompanied by a great deal of black and white art provided by Chris Brandt, John Larrey, Stefan Poag, and Sholtis himself.

Before proceeding further, I should note that the author extends his special thanks to me, among others, though for precisely what I cannot say, as I had nothing whatsoever to do with the creation of The Dungeon Dozen, except perhaps to encourage Sholtis to pursue his plans to collect together all his delightful tables under one cover. After a lengthy table of contents, the book is arranged alphabetically according to the title of the random tables. Thus, it begins with “Additional Nuisances in the Frozen Wastes” and ends with “Zealots in the Streets.” In addition to the table of contents, there are two additional tools for using the book: a “quick reference” based on subject matters (e.g. “Enchanted,” “Underworld,” etc.) and a full index of both topics and references. Blogger Jeff Russell has rather helpfully provided an online index of all the topics covered in The Dungeon Dozen here, which should also give you a really good sense of its content.

Before proceeding further, I should note that the author extends his special thanks to me, among others, though for precisely what I cannot say, as I had nothing whatsoever to do with the creation of The Dungeon Dozen, except perhaps to encourage Sholtis to pursue his plans to collect together all his delightful tables under one cover. After a lengthy table of contents, the book is arranged alphabetically according to the title of the random tables. Thus, it begins with “Additional Nuisances in the Frozen Wastes” and ends with “Zealots in the Streets.” In addition to the table of contents, there are two additional tools for using the book: a “quick reference” based on subject matters (e.g. “Enchanted,” “Underworld,” etc.) and a full index of both topics and references. Blogger Jeff Russell has rather helpfully provided an online index of all the topics covered in The Dungeon Dozen here, which should also give you a really good sense of its content.

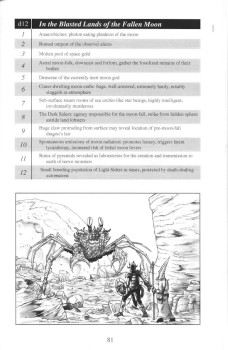

Typically, there are one or two tables per page, often accompanied by an illustration. A couple of sample pages are included along with this review to give some impression of what it looks like. These samples don’t do complete justice to the book, though, because it is so sumptuously illustrated (including several full-page pieces) that is difficult to describe in full. What I can say is that the art has a pulpy feel that evinces both whimsy and dark humor, the cumulative effect of which, after flipping through the book, is intoxicating. This isn’t a book of “vanilla” fantasy illustrations, nor is it one filled with superheroes and supermodels. It’s a captivating trip into a weird world that reminds the reader of what fantasy looked like in the days before the genre was yet another Hollywood-ized big business.

Typically, there are one or two tables per page, often accompanied by an illustration. A couple of sample pages are included along with this review to give some impression of what it looks like. These samples don’t do complete justice to the book, though, because it is so sumptuously illustrated (including several full-page pieces) that is difficult to describe in full. What I can say is that the art has a pulpy feel that evinces both whimsy and dark humor, the cumulative effect of which, after flipping through the book, is intoxicating. This isn’t a book of “vanilla” fantasy illustrations, nor is it one filled with superheroes and supermodels. It’s a captivating trip into a weird world that reminds the reader of what fantasy looked like in the days before the genre was yet another Hollywood-ized big business.

As compelling as the art is, it’s the content that I think is most noteworthy about The Dungeon Dozen. Each table has twelve entries–which I appreciate, being a noted dodecahedron fancier myself – that highlight Sholtis’s considerable gifts for both bizarre fantasy and wry commentary. For example, one of the entries on the “Famous Swords and Current Whereabouts” table is “Hronar’s Holy Brand: non-lethally embedded in demon lord,” while another is “The Hairsplitter: on mantle at big city lawyer’s club.” Meanwhile, “Dungeon Level Three: Memorable Features” includes “Forum of the prehumans now used by cultists for public execution of heretics, captured enemies (especially numerous: albino mermen)” and “Giant river monster like a fetal bird that projects beams of terror from its unopened eyes.” These tables and entries all carefully straddle a line between being too generic and too specific, both of which would make them difficult to drop into an existing campaign without heavy modification. To my mind, that’s quite a remarkable feature and one I wish more RPG supplements of this sort managed with such ease.

If I have any complaints about The Dungeon Dozen, they are small. There are some typos and similar errors here and there, but, given the amount of material included, this is hardly surprising and certainly not a deal-breaker. Because of how many tables are included, even with the quick reference and index, it’s not always easy to know what’s included, which limits its immediate utility. I suspect, with time and use, one will become much more familiar with its contents and know precisely which tables are present and whether they’re applicable to one’s current needs. Again, that’s a quibble and doesn’t detract from what is, to my mind, one of the most interesting and usable game products to come out of the Old School Renaissance in some time. I should add that, while The Dungeon Dozen is most obviously of use to the referee in stocking dungeons, imagining NPCs, or creating treasures, there are also many tables of interest to players as well. The “Before First Level” series, to cite but one example, provides quick and dirty backgrounds for newly generated characters. As a result, I’d recommend this book highly to anyone who enjoys old school fantasy roleplaying games and appreciates the matchless inspirations that well done random tables can provide.

I’ll have to look into the blog, and perhaps the book. Very interesting lists with just enough information to spur the imagination without boring things down into a bunch of stats.

I also love the artwork. Very early TSR feel to them.

I LOVE books like this! I hadn’t heard of this one, James. Thanks for spreading the word! It’s now on my “must by” list.