The Cleric and the Crucifix

“Come to me, Arthur. Leave these others and come to me. My arms are hungry for you. Come, and we can rest together. Come, my husband, come!”

There was something diabolically sweet in her tones — something of the tingling of glass when struck — which rang through the brains even of us who heard the words addressed to another. As for Arthur, he seemed under a spell; moving his hands from his face, he opened wide his arms. She was leaping for them, when Van Helsing sprang forward and held between them his little golden crucifix. She recoiled from it, and, with a suddenly distorted face, full of rage, dashed past him as if to enter the tomb.

So does Dr. John Seward describe the encounter between Abraham Van Helsing and newly-risen Lucy Westenra in Chapter 16 of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. I’m not knowledgeable enough in literary vampire lore to be able to say with any certainty that the 1897 novel is the first time we see a bloodsucker recoil from a crucifix, but, even if it’s not, I have little doubt that it was probably the most widely-read and influential example of it. Not only has the novel itself sold untold copies in the English-speaking world alone, but motion picture adaptations, starting with F.W. Murnau’s unauthorized 1922 film, Nosferatu, have added much to the popular conception of “the undead” (to borrow Stoker’s own coinage) – and how to combat them.

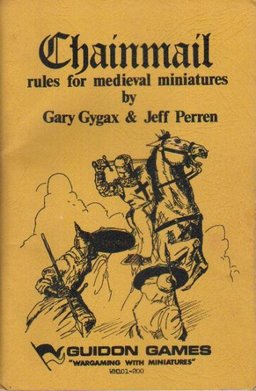

In the world of gaming, it’s well-known that the medieval miniatures rules, Chainmail, written by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren, was the immediate predecessor to Dungeons & Dragons, especially its “Fantasy Supplement,” which introduces the option of including magic and monsters so as to “refight the epic struggles related by J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert E. Howard, and other fantasy writers.” Even a cursory examination of Chainmail reveals that there’s nary a mention of religion in its pages, including in the Fantasy Supplement. This shouldn’t really come as a surprise, since the priest isn’t a distinct literary archetype in the pulp fantasy literature that inspired Gygax (as revealed in innumerable posts about his Appendix N bibliography on this site and elsewhere). Consequently, Chainmail includes only “heroes” and “wizards” as individual units.

When D&D first appeared in 1974, there were fighting men and magic-users, just as in Chainmail, but there was also a third type of character: the cleric. Their description in Volume 1 of the original edition is rather vague about their nature, noting primarily that they “gain some of the advantages from both of the other two classes (Fighting-Men and Magic-Users),” that they “receive help from ‘above,'” when raising funds to build a stronghold, and that their men-at-arms are “faithful.” The first statement is intended to highlight the hybrid nature of the class, being both a caster of spells and able to fight with some efficacy. The latter two statements hint at the religious nature of the class (as does the name, of course), a fact made more clear when you look at the cleric’s spell lists, which reference miracles from the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, such as turning sticks to snakes, summoning a plague of insects, creating food, and raising the dead. Even so, isn’t it odd that D&D includes a religiously-oriented character class while Chainmail does not? What happened in the transition from miniatures wargame to tabletop roleplaying game that warranted the creation of this new class?

When D&D first appeared in 1974, there were fighting men and magic-users, just as in Chainmail, but there was also a third type of character: the cleric. Their description in Volume 1 of the original edition is rather vague about their nature, noting primarily that they “gain some of the advantages from both of the other two classes (Fighting-Men and Magic-Users),” that they “receive help from ‘above,'” when raising funds to build a stronghold, and that their men-at-arms are “faithful.” The first statement is intended to highlight the hybrid nature of the class, being both a caster of spells and able to fight with some efficacy. The latter two statements hint at the religious nature of the class (as does the name, of course), a fact made more clear when you look at the cleric’s spell lists, which reference miracles from the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, such as turning sticks to snakes, summoning a plague of insects, creating food, and raising the dead. Even so, isn’t it odd that D&D includes a religiously-oriented character class while Chainmail does not? What happened in the transition from miniatures wargame to tabletop roleplaying game that warranted the creation of this new class?

The answer can be found in what some might call the cleric’s signature special ability, which was tucked away in a little table in Volume 1 with the suggestive title of “Clerics versus Undead Monsters.” Though given very little explanation, this table provides for the cleric to be able to “turn away” or “dispel” an undead creature, including the dreaded vampire, which is the most potent undead monster in the 1974 edition of D&D. Though there are undead monsters in Chainmail (such as wights and ghouls), there are no vampires. Once vampires did appear in the game, along with many other undead creatures, we begin to see echoes of Van Helsing, including the list of equipment characters in the game may purchase. The list includes both wooden and silver crosses (as well as holy water) in addition to the expected arms and armor. Furthermore, Dave Arneson‘s Blackmoor campaign – Ground Zero for the RPG explosion – owes its origin, as he explained in a 1998 interview with Allen Varney, to “watching about five monster movies on channel 5’s ‘Creature Feature’ weekend,” a campaign that would eventually include a vampire player character who became such a threat to the other characters that a powerful foil to him was needed. That foil came to be called the cleric.

Initially, then, the cleric was a medieval Christian monster hunter on the model of Van Helsing as memorably played by Peter Cushing in the Hammer Studios films of the 1950s and ’60s, many of which were shown on Friday nights and Saturday afternoons on TV stations across America throughout the 1970s. Though a generation younger than Arneson, I too spent weekends watching them from behind the safety of a chair. Though remembered more for their luridness and gore, what struck me as a younger person about Hammer’s movies was their stark delineation between good and evil, as well as the suggestion that, ultimately, good was the more potent. Dracula might be powerful and charismatic; he might cut down many a stalwart man and lure many a nubile woman to her doom, but he was always defeated in the end. Just as noteworthy was that Van Helsing won his victories with crucifixes and holy water, the very same accouterments found on the equipment list in Dungeons & Dragons.

Nowadays, thanks in no small part to Dungeons & Dragons, the cleric has become a much more prominent literary archetype in fantasy. Of course, this archetype is, like the cleric class itself, “generic,” suitable for service to any divinity one might wish to imagine. He may now wield a “holy symbol” rather than a crucifix, but the cleric retains his power over the undead, an ability whose only warrant is in the tales of vampires and those who seek to end their villainy. I find this a fascinating evolution, even as I hope that more people – roleplayers and otherwise – become aware of the true origins of the cleric.

I’ve noticed over the years that vampire movies have slowly gotten rid of the holy symbol as a means of fighting the undead. My guess is that this has more to do with the evolving pluralism of our society today than any sort of purposeful downplaying of religion.

A somewhat humorous meta-comment on this can be seen in the 1999 movie The Mummy when the mummy in question confronts his soon to be accomplice Beni. Beni, in great fright, begins pulling out various holy symbols (Muslim, Jewish, etc.) in hopes that at least one will ward off the mummy.

[…] of the Rings had a profound impact on the creation, development, and subsequent success of D&D. As I’ve noted before, the “Fantasy Supplement” of Chainmail, which is D&D‘s immediate forebear, […]