Cynthia Ward Reviews Lost Things

Lost Things: Book I of the Order of the Air

Lost Things: Book I of the Order of the Air

Melissa Scott & Jo Graham

Crossroad Press (350 pp, $17.99, Paperback, $4.99, eBook, 2012)

Reviewed by Cynthia Ward

I first encountered Melissa Scott’s fiction in her second novel, The Roads of Heaven (1988), which is the first book of the Silence Leigh trilogy. I ended up reading all three novels, intrigued by their smart blending of familiar science fiction and fantasy elements (magic, interstellar travel, a gender-inequitable future) with a strong female lead, sharp prose, excellent characterizations, exceptional world-building, a quick pace, and an insightful exploration of gender roles. Despite a major lack of reading time, I made sure to read all subsequent Scott novels I saw, including her occasional collaborations with her partner, the writer/editor Lisa A. Barnett.

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, I stopped seeing new novels from Scott. I would puzzle over the sudden disappearance of a favorite author until, years later, I would learn that Scott’s partner of 27 years had passed away after a long struggle with cancer. I hoped that Scott would eventually return to writing, while understanding why she might not.

Well, Melissa Scott has returned. And she’s done so in less a whirlwind of activity than a tornado. She’s released a pair of new collaborative novels set in the Stargate Atlantis universe, and a new solo novella set in the Elizabethan-esque world of Astreiant, which she created with her late partner. Their previous Astreiant titles are being reissued, along with several of Scott’s other backlist titles. And she recently released another new novel, set in the shared world of the Orphic Crisis Logistical Taskforce series, and written in collaboration with Jo Graham, an author previously unknown to me. It is this last work, Lost Things: Book I of the Order of the Air, which concerns us here.

The byline Melissa Scott would be enough to persuade me to read this collaboration; but the novel offers a second enticement: its time period. Drawing on Scott’s background as a historian, Lost Things is set between the First and Second World Wars. The 1920s were the era of jazz and Prohibition and Art Deco, of the Harlem Renaissance and F. Scott Fitzgerald and the Lost Generation, of aviatrices and airships and the extension of voting rights to American women. It’s a particularly fascinating era, yet comparatively underused in historical fantasy.

Lost Things opens in May 1929, as archaeologists in the employ of the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, drain Lake Nemi. A volcanic lake, Nemi was once known as Speculum Dianae (Diana’s Mirror), and was sacred to the eponymous goddess. In an act of national pride, the Italians are uncovering a millennia-lost archaeological treasure: remarkably large, technologically advanced ships dating from the reign of the mad Roman emperor, Caligula.

Or, rather, the ancient world thought Caligula was mad. In Scott and Graham’s alternate (or secret) history, Caligula was possessed by an extremely powerful demon or spirit, which Caligula’s successor, the Emperor Claudius, and the moon-goddess, Diana Nemorensis, imprisoned beneath Lake Nemi. This binding worked for two millennia. Then an artifact is stolen from the archaeological site, releasing the demon–as power-hungry as ever–into the world of 1929.

Half a world away, veteran aviator Lewis Segura awakens from a frightening dream. It’s not one of his usual nightmares, haunted by memories of the Great War. It’s an eerie dream of a lake he’s never seen before, and underwater monsters, and a white hound waiting for him in a dark and unknown wood. He sometimes has prescient dreams, and he always recognizes a dream that’s going to come true, no matter how strange. And this, while strange beyond understanding, is one of his true dreams.

It’s not a talent Lewis expects anyone to believe, so he keeps it to himself. Anyway, the true dreams usually portend bad events; and this dream feels particularly grim. Certainly, it’s in a different league than the soaring vision which led him both to his piloting job, which he loves, and a woman named Alma “Al” Gilchrist, for whom he’s not quite sure what to feel. Alma’s an aviatrix. She’s a war widow who, as an ambulance driver during the Great War, is herself a veteran. She’s a co-owner of Gilchrist Aviation, and therefore Lewis’s boss. She is also, in defiance of all proper morality, Lewis’s lover. She’s unconventional to a remarkable extreme, but how could even a woman this remarkable believe her lover’s dreams come true?

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that Lewis’s true dream is about the freed demon; that Lewis and his employers must find a way to defeat it, with the fate of the world at stake; or that Alma and her business partners and friends, the veteran ace Mitchell Sorley and the war-damaged archeologist Dr. Jerry Ballard, are not surprised by Lewis’s precognition. The three are members of a small occult lodge, associated with an offshoot of the Golden Dawn, and known as the Aedificatorii Templi. Their group hasn’t been very active since they lost a key member, Alma’s late husband. But when they encounter the stolen Roman artifact in the possession of airline and movie studio owner Henry Kershaw, the group attracts the body-hopping demon’s attention, and Jerry is nearly murdered. The group must learn how to work with Lewis if it’s to have a hope of binding the demon once more.

I enjoy fantasy fiction, yet I have near-zero interest in occult fiction. I’m not sure why. I suppose I’ve encountered too much occult fiction which, like some Christian fantasy and New Age fantasy, gives off too strong a scent of True Believer. Even Alan Moore, the greatest comic book writer who has ever lived, has been unable to persuade me to finish his occultish Promethea series. And I love Alan Moore’s writing.

So, when I say Lost Things eased me right through its occult revelation without a hitch, and kept me turning pages until the end, you’ll know Scott and Graham handle the occult elements with a light and sure touch. And if you inferred that they must be doing other things right, too, you’d be correct. Their prose, characterizations, sense of time and place, and world-building are exceptionally good. And these elements, while strong and effective in themselves, gain further strength from the way they interact.

Actually, “interact” is the wrong term. It’s more accurate to say that the prose, characterizations, sense of time and place, and world-building are the facets of a diamond: they’re all aspects of one thing. And that thing–the diamond of Scott and Graham’s novel–is their masterful command of viewpoint.

Consider this random example, from the viewpoint of Dr. Jerry Ballard:

“Jerry followed [Henry Kershaw] down the hall, the knob of his artificial leg skittish on the tile floors. It was time Alma added another layer of rubber–past time, really, but they’d been in a hurry leaving Colorado. To either side, wide doors revealed expensive furniture, sunlight hanging in the still air; the sound of water was suddenly louder, and the hall opened onto a wide terrace that overlooked a semi-enclosed patio. A fountain played in the center, and outside a swimming pool glittered in the sun, and beyond it was a low-roofed pool house faced with a pillared loggia. Jerry tipped his head to one side, abruptly aware of a change in energy, and looked at Henry.”

In a single paragraph, you’re simultaneously embedded in the viewpoint character’s mind, body, perceptions, surroundings, past, and even (in the closing phrase) future. You feel his difficulty in walking on tile and his keen awareness of his surroundings even while distracted. And while Jerry notices much about his surroundings, his creators don’t cross the line of providing too much detail–providing more information than the reader wants, or can process. And, with the exception of the slightly rough opening (which orients the reader from the demon’s viewpoint), the entire novel unfolds in this effective, fluidly organic, and ceaselessly engaging way.

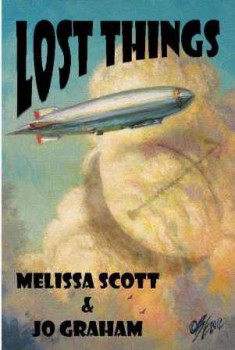

It’s a subtle skill, an impressive book-length balancing act. It’s beautifully captured in Bob Eggleton’s cover art, in which the novel’s airship balances dreamily with symbols of the moon-goddess in the dreamlike sky of another age. And it makes Lost Things a decidedly difficult novel to put down.

I hope you’ll pick it up. I know I’ll pick up the forthcoming sequel, Steel Blues.

___________

Cynthia Ward has sold fiction to Asimov’s SF Magazine and Pirates & Swashbucklers, among other anthologies and magazines. She has sold nonfiction to Weird Tales and Locus Online, among other webzines and magazines. Her story “Norms,” published in Triangulation: Last Contact, made the Tangent Online Recommended Reading List for 2011. With Nisi Shawl, she coauthored Writing the Other: A Practical Approach (Aqueduct Press), which is based on their diversity writing workshop, Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction.

[…] Cynthia-Ward-reviews-Lost-Things […]