Robots Have Tales: Henry Kuttner’s Gallagher Stories

Apologies for my radio silence last week. Candidly, I was at a loss for a subject, until Fate and Amazon put the perfect book into my hands (which I’ll talk about below), which wasn’t until sometime late in the week.

Apologies for my radio silence last week. Candidly, I was at a loss for a subject, until Fate and Amazon put the perfect book into my hands (which I’ll talk about below), which wasn’t until sometime late in the week.

And, with further apologies, here’s a self-pimping update: there’s still time to participate in the discussion of Blood of Ambrose at Stargate producer Joe Mallozzi’s blog.

As to the “perfect book”–the new issue from Paizo Press’ Planet Stories line, Henry Kuttner’s Robots Have No Tails, may not be perfect in some absolute sense (although it comes pretty close) but it’s certainly one that I and others have been looking forward to for years. And it’s only the latest (hopefully not the last) in a series of Kuttner reprints from Planet that now includes Elak of Atlantis, his pioneering sword-and-sorcery stories, and The Dark World, probably the best of his swashbuckling adventure tales. (I say “probably” only because I can’t claim to have read all of Kuttner–maybe no one has, although Planet publisher Erik Mona has certainly come closer than most.)

[Sagrazi the unvastenable beyond the jump.]

_____

Kuttner was an amazingly deft pulp writer who could generate any sort of imaginative fiction a market required. He unquestionably made his biggest splash as the archetypal writer of John W. Campbell’s magazines, Astounding and Unknown (under his own name and others, writing solo and in collaboration with his wife, C.L. Moore).

That may be why his reputation has suffered. Writers and magazines in the 1950s and afterwards often made their reputations by not offering the type of thing associated with Campbell’s magazines. Astounding (now, of course, Analog) wasn’t just a relic: Dune first saw light there, among other important work. And it isn’t yet: it still has the best circulation of the print sf magazines. But Kuttner died young, and even before that in the 1950s his output had dried up; he never escaped Campbell’s shadow.

Earlier Kuttner volumes under the Planet imprint have been more on the fantasy side; Robots Have No Tails, however, is Campbellian sf of the purest grade–the clear quill, as it were. In each one, the unpredictable scientific genius of the drunken Galloway Gallagher creates a problem which the less-brilliant, more-nearly-sober Gallagher has to solve. The stories were early collected (under the present title) by Gnome Press in 1952, and reprinted in 1973 by Lancer Books. And, if you haven’t read them before, that explains why: Gnome Press long ago vanished in a cloud of broken promises; and books from Lancer were not designed for permanence–it was a rare copy that survived a single reading without the cover falling off or the pages dropping out.

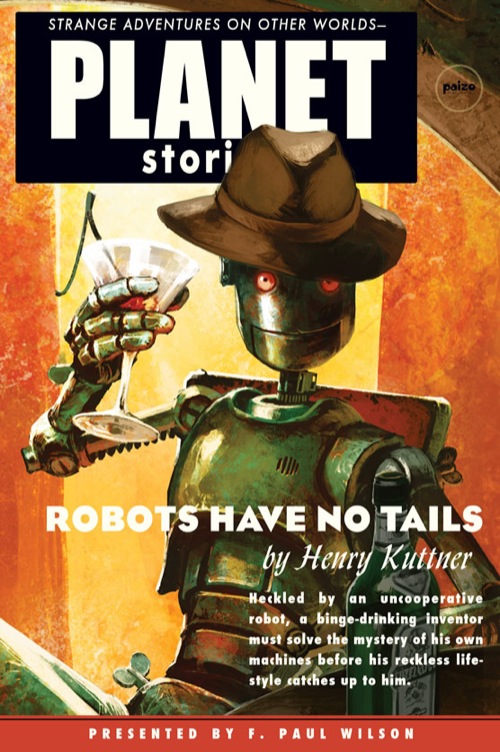

The new Planet books edition contains all five of the Gallagher stories, the C.L. Moore introduction to the Lancer edition and a new intro by F. Paul Wilson. It also represents a change of format for the line, more like an issue of an old magazine than a contemporary trade paperback. The cover and interior art is pulpier. (The witty 1940s-themed cover is by Tomasz Jedruszek; the sly interior drawings are by Brian Snoddy.) The table of contents is organized like a magazine’s; the pages are in the old double-column format; there is even a black-and-white 1940s-style advertisement in the back of the book, containing enthusiastic testimonials from ordinary readers like “N.W. Smith” and “Matthew Karse”. On balance, I think this is all good. The one drawback to the new format is the paper of the book itself: it’s lighter than the stock Planet previously used, lower in contrast, and is likely to be less durable.

I’m not sure I can describe the stories themselves without ruining them for new readers. Each one is a joke of some kind; each one of them is a problem story; each one is decorated with Kuttner’s unique form of rational insanity. His most famous story is probably his collaboration with C.L. Moore, “All Mimsy Were the Borogoves” (not reprinted here, because it’s not a Gallagher story), and Kuttner’s affinity for Carroll’s nonsense is undeniable. These stories read as if the Cheshire Cat or the Mad Hatter had been given a typewriter and told to write science fiction as if their lives depended on it.

Here are the Lybbla, for instance, from “The World Is Mine” (my favorite of the stories). They are bunnylike Martians from the future, who have snuck back in time through a time machine of Gallagher’s invention on a savage and unalterable mission to conquer the Earth.

“First we destroy the big cities,” said the smallest Lybbla excitedly, “then we capture pretty girls and hold them for ransom or something. Then everybody’s scared and we win.”

“How do you figure that out?” Gallagher asked.

“It’s in the books. That’s how it’s always done. We know. We’ll be tyrants and beat everybody. I want some more milk, please.”

Other standout characters include the vain, transparent robot Joe (a.k.a. Narcissus), who was invented by Gallagher for the most obvious of reasons (in retrospect), but who has unexpected talents like vastening (which is “rather like a combination of sagrazi and prescience,” if that helps).

Not all the jokes still work. Campbell’s magazines had a fair amount of extremely dated dialect humor, and Kuttner obliges this depraved taste with a strangely menacing diamond merchant afflicted by the WASPy moniker of Kennicott and an Italian accent like a organ-grinder from an old Warner Brothers cartoon. (“Ah-h, nutsa. I waita one day. Two daysa, maybe.”) He’s more funny in theory than in practice, but he doesn’t show up much. In addition, the prospective reader simply has to accept that Gallagher’s continual drunkenness is funny and not tragic: this is not a book to pass around to your friends in Al-Anon, in short.

Also, these stories don’t constitute an exercise in coherent world-building. (Unlike, say, Kuttner’s Fury and its companion piece, the excellent “Clash by Night”.) Kuttner reportedly forgot his inventor’s name between the second and third story, calling him Galloway instead of Gallagher, and solved the problem in the fourth story by making Galloway his first name. Likewise, significant world-details change between the stories. In the first story (“Time Locker”), the corpus delecti is an essential element for a murder case: without a body, any case will get tossed out of court. But in the last story, Gallagher’s peril is based (in part) on the premise that a murder charge can be proved against him even without a dead body to support the charge. One could cobble up a rationalization to connect these two dots (and others like them), but the real explanation seems to be the same one as for Gallagher’s name: Kuttner (writing in a hurry, without access to the stuff he’d written earlier) made each story consistent with itself, but the stories aren’t consistent with each other.

The plots are carefully constructed traps from which the hero eventually manages to escape, and as such they work as well as when they were written. But the best thing about them are the details that don’t need to be there, the jagged chunks of Kuttner’s untameable id set like gems in the smooth metallic glitter of his professional skill, the parts that the reader could not have vastened but that Kuttner somehow manages to sagrazi.

[…] http://www.blackgate.com/2009/07/08/robots-have-tales-henry-kuttners-gallagher-stories/#more-2622 Posted by Blue Tyson 3.5, study, t non-fiction, z free sf Subscribe to RSS feed […]

[…] http://www.blackgate.com/2009/07/08/robots-have-tales-henry-kuttners-gallagher-stories/#more-2622 […]

[…] stories were collected by Paizo in Robots Have no Tails (reviewed for us by James Enge here), and Paul Di Filippo recently reviewed Moore’s seminal collection Judgment Night for us […]