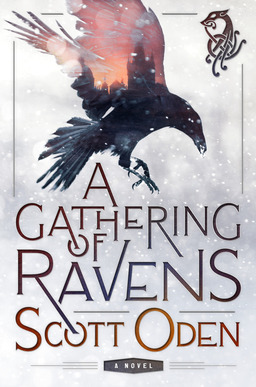

I really wanted to like this book. With pleasure I listened to Oden speak on The Literary Wonder and Adventure Show. He talked at length about Tolkien (my own spiritual and literary master), and it seemed that Oden’s and my dials were approximately set. Oden’s book, like Tolkien’s most popular works, deals with “that northern thing” (though I just today learned that Tolkien objected, in part, to this characterization from W.H. Auden).

I really wanted to like this book. With pleasure I listened to Oden speak on The Literary Wonder and Adventure Show. He talked at length about Tolkien (my own spiritual and literary master), and it seemed that Oden’s and my dials were approximately set. Oden’s book, like Tolkien’s most popular works, deals with “that northern thing” (though I just today learned that Tolkien objected, in part, to this characterization from W.H. Auden).

But Oden’s book is so grimdark that, while reading, I couldn’t find my feet. The work ostensibly is about an orc Hel-bent on revenge — and here is my first objection: the attitudes and actions of this orc, our “protagonist,” are indistinguishable from those of the larger majority of characters in the book. Grimnir, our orc, seems capable only of speaking and thinking in profanities. He murders even when there absolutely is no reason to. The only thing (in this book) we can’t accuse Grimnir of is the sin of rape. That assault remains to be committed by many of the other “human” characters you will find therein: your average male, in this portrayal, seems hardwired to enter rape mode the moment he lays eyes upon any “unprotected” female. Now, remember, Grimnir is supposed to be the “orc,” yet he doesn’t behave much differently from the novel’s many other human characters. Moreover, even when it doesn’t cost a character anything necessarily, few characters are liable to show any shred of kindness for one another. Oden’s narrator summarizes this world’s milieu thusly: “She [the character Etain] knew the score … and she knew sooner or later there would be a reckoning. Men did nothing — undertook no good deed, performed no kindness — without first attaching a price to it.” Oden’s characters, I suppose, are consummate Dark Age businesspersons.

“But that’s the Way It Was,” a number on Goodreads might say, defending Oden’s work from the very few negative reviews I can find there (here and here are two well-said assessments). What these apologists are claiming is that the worldview of the so-called Dark Ages is exactly this: murder whenever you can get away with it, rape whenever you like (for those who like it, I guess, who are all young pre-modern men). I don’t entirely agree with this representation. In the worst possible reading, this might represent the author’s views of the natural state of humankind freed from the fetters or checks thankfully supplied by modernity. In the best possible reading, this representation assumes that, at least in the area of moral development, humans who happened to live a mere millennia ago might be considered pre-human in these respects. Granted, the spread of more nation-building and socializing beliefs and philosophies such as Christianity might have a civilizing influence on a pre-modern worldview, might even be of some aid in the sense of an evolving moral consciousness. But this book barely acknowledges even this. It ostensibly presents two competing worldviews, that of northern paganism and that of Christianity, but, in this book, in practice adherents to either faith might as well be indistinguishable. They merely serve one team in a two-sided competition that is drawn as equal in every respect. Again, apologists should be quick to point to aspects of history that reveal a number of Christians as hypocritical and intolerant throughout their persecutions. Granted, but are you going to deny that there remain some fundamental differences and worldviews between the two perspectives, and therefore requisite actions and behaviors on behalf of the religion’s adherents? To this point Oden seems to relent, to some measure, in the second and much-preferred half of the book, in the figures of King Brian and his freed thrall Ragnar. But we’ll get to that in a moment.

…

Read More Read More