Revealing the Cover — and an Excerpt — from Robert V. S. Redick’s Sidewinders

We’re big fans of Robert V. S. Redick here at Black Gate. I’ve lost count of how many of his books our staff has enthusiastically reviewed over the years but… whew, it’s a lot. That’s why we’re so excited at the impending release of Sidewinders, the second volume in The Fire Sacraments series (following Master Assassins, which we covered — you know it! — right here back in 2018).

As if we weren’t excited enough already, Black Gate website editor emeritus C.S.E. Cooney sent us this blurb for the book and I have to tell you, it wound us up pretty good. Have a look.

Sidewinders. I love this book, goddamnit. Robert V. S. Redick gives a fantasy reader everything her fiendish heart craves: plagues, prophets, demonic possessions, a desperate dash through desert dunes, giant spiders, giant cats, creepy children, plenty of vulgarity and sex, and an all-too-brief glimpse of paradise. So sure, if you like that kind of thing, go for it. Read this book. It’s for you. But wait, there’s more. For your not-so-average fantasy reader, your not-so-run-of-the-mill genre-lover, I beg you, look to Sidewinders. For it will give you ambiguity and delicacy. It will not spare you of its irony — and, oh, such irony! Its pages will impart so profound and aching an empathy that it just might leap off the page and follow you into your daily life. There is such courage in Robert V. S. Redick’s Sidewinders — such courage and fury and passion and hope. Truly a breathtaking work.

—C.S.E. Cooney, author of the forthcoming Saint Death’s Daughter, on Sidewinders

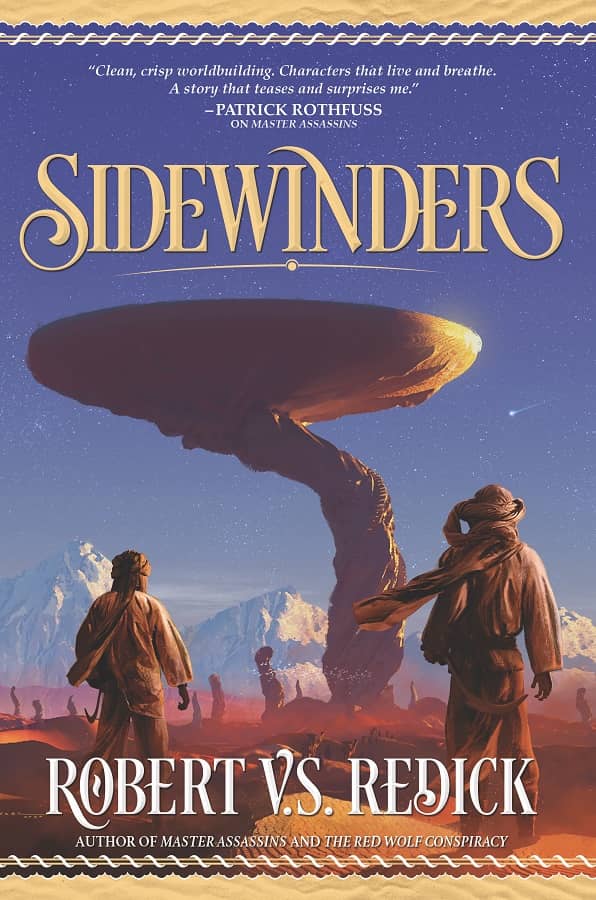

Talos Press will be publishing Sidewinders on July 6, 2021. Wunderkind PR were kind enough to send us a high-resolution sneak peek of the cover to share with you — and also a tasty excerpt from Chapter One of the book.

Without further ado — check out the gorgeous cover, featuring artwork by Mack Sztaba!

[Click the image for a full-size version.]

Art by Mack Sztaba; cover design by Shawn T. King

It’s no exaggeration to say we’ve been telling you about Robert’s top-notch fantasy for over a decade. Here’s a sample of some of our previous coverage over the last eleven years.

Wrestling with Genre: An interview with Robert V. S. Redick on Master Assassins by C.S.E. Cooney (2018)

Master Assassins by Robert V. S. Redick (2018)

The Series Series: The Night of the Swarm by Robert V.S. Redick by Sarah Avery (2014)

Not So Short Fiction Review: The River of Shadows by Soyka (2011)

Ruling Sea Review by Soyka (2010)

Ready to dive in? Below is a 2,800-word excerpt that comprises roughly the first nine pages of Chapter One. While Sidewinders continues the story begun in Master Assassins, it can also be read as a standalone.

(Already read Master Assassins, and ready to order today? Order online at B&N here.)

Caution: This excerpt contains strong language, and is intended for mature audiences.

An Excerpt from Sidewinders

By Robert V. S. Redick

This is an excerpt from Sidewinders, by Robert V. S. Redick, presented by Black Gate magazine. © 2021 by Robert V. S. Redick.

It appears with the permission of Robert V. S. Redick, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Sidewinders will be published by Talos Press on July 6, 2021. It is 672 pages long, priced at $26.99 in hardcover. Get all the details at robertvsredick.com, and order your copy at the B&N online bookstore.

Chapter One: The Wasp

Vasaru Gorge, Outer Basin, Great Desert of Urrath

79th day of winter, 3661

The pit had appalled him even before he learned what it contained.

From the plateau above it was merely a round hole in the earth, but as they descended it took on a quality of menace. Broad, black, dry as a desert tomb. Here on the canyon floor it gaped at him, promising nothing but disaster, a chill wind moaning across its mouth. He had no wish to approach it. Who in their right mind would?

Come, urged the camel drivers, breath blooming white through chattering teeth. Visit with us, a special place, the Well of Riphelundra, once only, mandatory.

“What’s down there?” he asked.

Smiling at his unease but nervous themselves, they took his arms and led him straight for the pit. Fourteen men, nudging, hustling. You have to look, Mr. Kandri, they murmured. Don’t you want good luck in the desert? Who knows if you will pass this way again? What if you die?

“That’s just what I was thinking,” he said.

Dawn had come; jackals sobbed in the hills. The camels stood immense and obdurate and the sun etched their sawtooth shadows on the canyon floor. The mercenaries lurched among the animals, blinking and grimacing; the Caravan Master was trimming his beard. Kandri’s toes were numb and his hands cramped with cold. Why me? he wanted to shout at the camel men. I’m a coward, see? I don’t even like basements.

Why us? their fixed smiles replied. We have just entered the desert, this great killer who dispatches even the best of us, the most sage and seasoned, indifferent as the rag that wipes the soot from the kettle. Now you appear and we must accept you, share our camels and our water and our way. They are rationed, life is rationed, why should we die that you might live?

“Aren’t we leaving?” he tried, more anxious with each step. “The saddlebags, my gear. I’m not ready for the march.”

First things first, Mr. Kandri. Spurn a blessing and you may not arrive at all.

* * *

The caravan had descended the ridge in darkness: ninety drivers, forty fighting men and women, a threadbare Prince and his lone retainer, a surgeon, a cook, a dour desert veteran bringing up the rear. One hundred fifty camels. A dozen goats to be eaten in stages. A crate of pigeons and a pocket owl, whatever that was. Two hairless dogs.

They were in mortal need of haste, but only a few of them knew why. The Caravan Master had forbidden Kandri and his companions to reveal the truth of their situation. When Kandri’s half-brother Mektu observed that the truth would encourage speed in just about anyone, the Master had given him a stern rebuke:

“I set the pace, and the rest comply. They need no further motivation. And you know nothing of the desert or its people to suggest such a thing.”

All the same they had set out before midnight; this daybreak pause was their first. As they marched him to the pit, Kandri glanced at the bleary-eyed company. One soldier sharpening her dagger, another limbering up against the cold. Two men burying the camel dung lest it give them away. Four figures hunched over a dying cookfire, and one pair of small, nimble hands, toasting flatbread on the blade of someone’s machete.

The owner of those hands looked up suddenly and met his gaze. Eshett, desert woman, quietest and most mysterious of his circle of travelers. She was to leave them at sunset tomorrow, when the caravan passed the turnoff to her people’s village.

Kandri rolled his eyes: Harmless game. They want to show me so badly.

Eshett’s face was inscrutable. Her eyes moved to the pit and back again and she shook her head almost invisibly. They were newly lovers. In the night they had crept away from the caravan, made love standing up in a cleft between boulders, the wind howling about them like a beast in pain, laughing at themselves, at the cold and discomfort, the shooting stars that kept bursting overhead as if in mock congratulations, knowing that her departure was certain, that to indulge in talk of some other ending would be to wound themselves with fantasy, that two days and one night remained to them and must not be lost to grief.

Besides, there were entanglements. Mektu himself loved Eshett, however boorish his attempts to show it. And the brothers were already divided, had nearly become enemies for a time, over a woman from their own clan.

“Never tell him about us,” Eshett had said the night before, as they held each other in the wind. “Promise me that before I go. You’ll win back the heart of that other, if she’s truly out there. And that will hurt Mektu enough.”

“What if I come looking for you instead? What if I take you home?”

She had laughed; the idea was preposterous. Neither Kandri nor his brother nor their Uncle Chindilan could ever go home. They could only run, evading as many of the Prophet’s servants as they could and killing the rest. The desert in its soul-swallowing vastness might yet save them, if they could lose their pursuers here, and emerge alive on its far shores.

In that abstract country beyond the sands, a city awaited them: Kasralys, ancient and eternal. They could dream of safety within its walls, and even, in time, some new path in life. But home? Never. Home was lost to them; all that remained of it was each other.

Kasralys. The city haunted him in dreams. Safety was the first reason they had to find it. But Kandri had a second, hidden reason, and he felt it more keenly than survival itself.

“Her name is Ariqina,” he’d said to Eshett, not knowing why.

“She’s waiting there, is she?”

Waiting. He could have laughed: when had Ari ever waited for anyone? But—

“She’s there, in Kasralys. She has to be.”

“Tell me something about her,” said Eshett.

Kandri held up his hand, showed her the worthless copper ring from the neck of a fever-syrup bottle he wore on his thumb. “She gave me this—”

“And made a joke about it being a love charm,” said Eshett. “That’s sweet, and boring, and you’ve talked about it before. Something else.”

Kandri thought for a moment, then smiled. “She told me once that if you saw an odd number of shooting stars it meant good luck for love or friendship, but an even number was terrible luck, because it could always be split in two. And that wasn’t like her, believing such nonsense. She’s a doctor. She knows how things work.”

“And Mektu loves this woman?”

“Mektu loves you, Eshett.”

They both knew he had dodged her question. “What about her own feelings?” asked Eshett.

Silence, alas, was not among his options. “She cared for us both,” he admitted. “But she cared for Mek the way you do for a brother. A very little brother. But with the two of us—”

“That’s why he resents you,” said Eshett, laughing. “Because you always get the girl.”

“What do you mean, always?” Kandri demanded. “Before you there was Ari. Before Ari there was no one.”

Eshett reached up and gripped his chin.

“Never a word about us,” she said again. “Promise me. Right now.”

Kandri drew a deep breath. He promised. But he added that his brother already suspected the truth. Mektu was jealous if they walked within six feet of each other, shared a biscuit, exchanged a glance. “How lucky for everyone,” said Eshett, “that I’ll soon disappear.”

* * *

The mouth of the pit was fringed with button cacti and dead grass. Radiant cracks gave it the likeness of a window pierced by a stone. He could have bolted when he saw Eshett’s reaction, that small but unmistakable No. He could have fought out of their grip and fled back to the main company. Safe for the moment. And branded spineless, craven, incapable of trust.

Closer, they urged him. This is a holy place. Do not refuse us please.

Kandri chuckled, a fly wallowing in tar. He had such fine, such excellent reasons to refuse. It was late. Soon the shadows would vanish and the heat would search them out. And the death squads on the road behind them: they would be searching too.

Don’t fear, Mr. Kandri, said an older man with one cataract-clouded eye. No danger unless you disturb it. Otherwise, it sleeps.

Kandri blinked at him. The language they shared was neither the drivers’ mother tongue nor his own. “What sleeps?” he demanded. “Are you telling me something lives in there? I thought you called this thing a well.”

Yes, yes! they all assured him. A mighty well, an Imperial well, the very life of the district in earlier times. With stairs, landings, carvings of the Gods, alcoves for the storage of tubers and grain. Broad here at the surface, but narrowing to a bottleneck in the depths, above the water source.

“There’s still water in that hole?”

Oh no—yes—maybe, gabbled the drivers, before arguing their way to a consensus. The world was drier now; the desert had advanced. Maybe water still flowed in the depths, but only a fool would seek it. The well had passed out of human hands. It belonged to the Wasp.

“Wasps, did you say?”

“The Wasp,” repeated the camel drivers.

They considered him warily, as though alarmed by the extent of his ignorance. Then Kandri saw his brother standing at the back of the crowd. Mektu’s long-fingered hands squirmed at his sides. His lips were puckered in bewilderment.

“The Wasp,” he said. “That makes no Gods-damned sense. How big is the Wasp?”

Some of the men threw their arms wide. Others tssk’d and pinched the air. The Wasp was tiny, unless it was huge. “I have a great idea,” said Mektu. “Let’s leave.”

Kandri nodded. The break was over; the Master’s aide was waving his red kerchief. But the camel drivers stood their ground. Eyes closed, fists pressed together beneath their chins. The oldest among them chanting in a whisper.

“Thanks for this, everyone,” said Mektu, overloud. “I mean it. We’re honored to have seen this dead, cold, creepy—”

“Mektu,” said Kandri, “they’re praying.”

Startled, Mektu uttered an obscenity, and the drivers flinched. Kandri glared at him, and Mektu hid his face in the crook of his elbow, as he did when overcome with shame. The drivers chanted—

Seedlings our people,

Flowering in dust,

Life where there was no life,

Brief mornings of green.

—and everyone crouched down to rub a little of the dry earth against their foreheads. Everyone save Mektu, who could not see what was happening.

Kandri considered a prayer of his own, for good behavior from Mektu. His brother had yet to insult the drivers in any ghastly way, but it would come. They had caught up with the caravan just three days before.

But what of your own behavior, Kandri? How close did you come to that worst of insults, spitting on an outstretched hand?

For it was suddenly clear to him that the camel drivers meant no harm at all. In their odd, alien way they had tried to befriend him, include him in a sacred moment. Him, and not his lout of a brother. And yet he had imagined the worst. A sacrifice! Madness, mutiny, the stranger flung into a hole! In the chilly morning his face began to burn.

He knew nothing of these people. They sewed gold and silver beads into the skin above their eyebrows. They smoked cheroots that smelled of savory and brine. The men were clean shaven. The women tied their hair up in complex piles each morning and shook them free after sundown. Men and women mingled only at night; by day they hardly seemed to speak.

Where did they come from? What country, what clan? Eshett had told him to mind his own business. They’ll let you know if they wish to, she said. And if not, you of all people should understand why someone might want to hide.

The prayer ended; the crowd stood straight. Mektu lowered his arm. One of the elders offered him a pinch of dust and mimed the ritual gesture.

“Oh Gods, sorry, shit.”

Mektu tried to rub the old man’s forehead. Kandri turned away—Hopeless, don’t torture yourself—and then the lunatic attacked.

* * *

He was just one of the camel men, a dusty face in the crowd. He struck Kandri in a flying tackle and knocked him right off his feet. They landed together, grappling, barely a yard from the pit. His attacker clawed at him, seeking his eyeballs, howling the Prophet’s name. His face awash with sweat and tears. Missing teeth, black gouging fingernails.

Then a knife. In Kandri’s mind something leaped. He caught the man’s wrist as the blade descended and the knife bit the earth beside his chin. He raised his head and seized the man’s whole ear in his jaws and hugged the man and rolled. The first snap was the blade breaking, the second his attacker’s thumb. A spasm of agony, a howl. He bucked to his feet in one motion and kicked the man in the stomach and drew his machete from its sheath.

“Kandri Hinjuman!” bellowed Mektu, triumphant. “That’s my brother! You do not fuck with this man!”

No other attackers. Twenty faces, staring, abashed. He could have brought the machete down for the kill but did not need to, the man had fainted from the pain. But—

The letter!

His hand flew to his chest. The calfskin pouch was still there; he could feel its rawhide stitching through his robe. He had not dared to part with it when they joined the caravan, and their slight possessions placed in saddlebags. He had sown the pouch to his old army belt and wore it sidelong across his chest. Now it never left his person, or his thoughts. How could it possibly exist, that letter more precious than his own life, than all their lives together? And how was he able to sleep at night, to walk or run or fight or breathe? Its few pages weighed no more than one of Eshett’s flatbreads, but it was crushing him, crushing him with its weight—

Kandri turned his head—and reeled. He stood just inches from the pit. He swayed, caught his toe on something, the black hole spun beneath him—

Mektu’s hand closed on his arm.

“Bleeding?”

“Don’t think so.” He wanted to vomit, but it was only nerves, cowardice, his mortal fear of being buried alive. The camel drivers, looking guilty, began to back away.

“Thank you, Mek,” Kandri whispered.

“Just a fucking minute,” shouted Mektu, freezing the camel drivers in their tracks. He pointed at the fallen man. “Who is this shit? What’s the Prophet to him? You sand rats have your own religion, don’t you? What do you need ours for? Are you trying to become Chilotos? If you are, you’re cracked. I’m a Chiloto. It’s not a clan you want to join.”

The camel drivers inched backward, studying them with more than a little horror.

“Not all believers are Chilotos,” growled Kandri, steadying himself. “And we’re unbelievers anyway now, you fool.”

“I know that,” snapped Mektu. “I forget, now and then I forget. Answer my question, somebody! What are you staring at me for?”

“Stop clowning,” said Kandri, “and speak Common if you want them to understand.”

Mektu obliged, unfortunately: “I’m not possessed, you know.”

Oh fuck.

Kandri tried to throttle him, but Mektu held him at arm’s length. “So what if I’m not like other men? That doesn’t mean I have a thing in my head. Don’t spread rumors, it’s a nasty habit.”

“There were no fucking rumors,” Kandri growled. “Ang’s blood, we just met them, get me out of here.”

But Mektu was no longer listening. “You worship the Prophet, eh? Some of you, any of you? Listen: we know all about her. We killed for her, we carried her flag. And she’s not what she claims, do you hear me? She’s no favorite of the Gods, she’s not invincible, she can’t listen to your thoughts or punish you from a distance, that’s nonsense, and anyway she’s a mess, all warts and wrinkles and bits of food in her teeth, and there’s this smell sometimes, it’s revolting, you’d think the woman dined on—help!”

The ground collapsed into the pit.

Oh, John, I must say I’m not happy with the format / theme change. SIGH. I’ll get used to it but it’s not as informative as before. Darn.