Birthday Reviews: Ray Nelson’s “Time Travel for Pedestrians”

Radell Faraday Nelson was born on October 3, 1931. Nelson has published under a variety of pseudonyms, including Ray Nelson, R. Faraday Nelson, and Jeffrey Lord. Nelson is also an artist.

Nelson’s novel The Prometheus Man received a special citation Philip K. Dick Award in 1983. In 2001 he was nominated for a Retro-Hugo in the Best Fan Artist category.

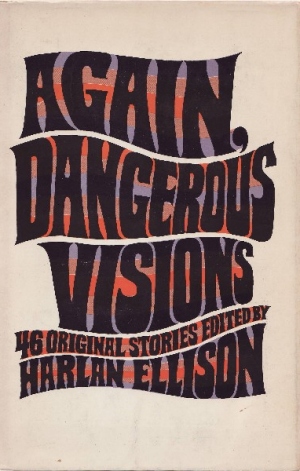

“Time Travel for Pedestrians” was published in Harlan Ellison’s Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972, and has been reprinted in the various versions of that anthology, but has not been published outside of that work.

While the framing device in Ray Nelson’s “Time Travel for Pedestrians” may have been transgressive in 1972, when it was first published, the combination of rumination on masturbation and drug trips seems self-indulgent at a forty year distance.

Going beyond the framing device, as least as much as possible, the story offers numerous past life regressions for Nelson’s narrator, each one set earlier than the one before, each focusing on the conflict between the spread of Christianity and its competing belief systems, and each ending with the death of Nelson’s protagonist.

Intriguingly, the further back in time the narrator finds himself, the more receptive he is of Christianity, starting with a new age paganism, eventually becoming a priest in the Inquisition, and finally taking dictation from Mary Magdalen. While Nelson’s reflections on each of these vignettes offers different views on religion and belief, the framing mechanism intrudes, raising the question of whether the narrator is actually reliving past lives or if everything is part of the drug trip he has initiated, and which undermines Nelson’s story.