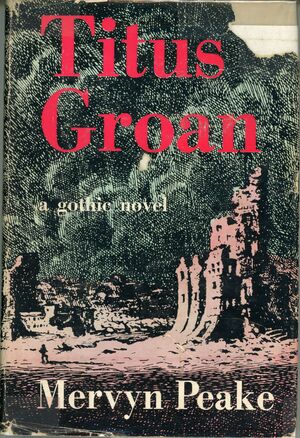

A Work of Pure, Violent, Self-Sufficient Imagination: Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake

Mervyn Peake‘s 1946 novel, Titus Groan, was intended as the first in a series that would follow the life of Titus Groan, Seventy-seventh Earl of Gormenghast, a vast, city-like castle set in a land of indeterminate latitude and longitude. Unfortunately, Peake was afflicted with what is believed to have been Parkinson’s Disease, and so finished only two other volumes, Gormenghast (1950) and Titus Alone (1959), and a novella, Boy in Darkness (1956). He succumbed to his illness in 1968, leaving only a few paragraphs and ideas for proposed future volumes. From those elements, his wife, Maeve Gilmore, completed a final book, Titus Awakes, which wasn’t published until 2009. By his son Sebastian’s account, it isn’t really a continuation of the series, but an attempt by Gilmore to address the loss of Peake.

Graham Greene helped edit Titus Groan into publishable form. Elizabeth Bowen and Anthony Burgess both thought highly of the book and Harold Bloom considered the Gormenghast trilogy the most accomplished fantasy work of the twentieth century. Michael Moorcock, a friend of Peake’s, has written several times about Peake’s artistry, and his own novel, Glorianna, is dedicated to Peake. Despite the support of so many writers, the books weren’t published for a second time until the late sixties by Penguin, and then as part of Lin Carter’s Ballantine Adult Fantasy line.

A satire of manners and a critique of blind adherence to dead tradition, despite having few clear fantastic elements it is easily one of the great literary works of fantasy. It might not match the success of The Lord of the Rings, but in its richness of imagination it does, and outpaces it in the depth and human variety of its characters.

Titus Groan opens on the day of the birth of its titular character and ends a year later when he is made Earl of Gormenghast. The story, while it revolves around his birth and accession, is not his, but that of several other characters, primarily Steerpike, a kitchen boy intent on forcing his way upward to a position of power in the castle.

Escaping the horrid Great Kitchen ruled by the even more horrid cook, Abiatha Swelter, Steerpike quickly realizes that the weight of Gormenghast’s customs and codes cannot be overcome, but might be subverted to his aims. Slowly, by charisma, guile, and plotting, he begins to do so. Subversion, arson, and murder are all relentlessly and remorselessly employed toward his ends.

Simultaneous to Steerpike’s ascent, Mr. Flay, servant to the current Earl, Lord Sepulchrave, is engaged in a war of wills with the cook, Swelter. Though the conflict plays out outside of everyone else’s observation, its conclusion has great ramifications in the second book.

Like a Dickens novel, the book is filled with numerous digressions and tangential side plots as well as a large assortment of minor characters. On their own, each may seem to do little to further Titus Groan‘s larger story, but taken together they deepen and enrich everything else in the novel.

Titus Groan is one of the great achievements of literary worldbuilding. Peake spent his childhood in China, the son of British missionaries. The segregated community he grew up in, as well as the model of the Forbidden City of the Chinese emperor, itself ruled by tradition and ritual, must have informed his conception of Gormenghast. From those raw elements, Peake created a world that is vast yet strictly confined, and limited by more than just walls.

In Gormenghast one is bound to his position by birth, by tradition, by obligation, forever. Steerpike’s flight from Swelter’s domain is an outright aberration.

The walls of the vast room which were streaming with calid moisture, were built with grey slabs of stone and were the personal concern of a company of eighteen men known as the “Grey Scrubbers”. It had been their privilege on reaching adolescence to discover that, being the sons of their fathers, their careers had been arranged for them and that stretching ahead of them lay their identical lives consisting of an unimaginative if praiseworthy duty. This was to restore, each morning, to the great grey floor and the lofty walls of the kitchen a stainless complexion.

The immutable and incomprehensible rules and customs of Gormenghast, understood to whatever extent only by Sourdust, the Lord of Ritual, crush everything, particularly Lord Sepulchrave. Under their burdensome weight, he has fallen into a constant state of melancholy.

The left hand pages were headed with the date and in the first of the three books this was followed by a list of the activities to be performed hour by hour during the day by his lordship. The exact times; the garments to be worn for each occasion and the symbolic gestures to be used. Diagrams facing the left hand page gave particulars of the routes by which his lordship should approach the various scenes of operation. The diagrams were hand tinted.

The second tome was full of blank pages and was entirely symbolic, while the third was a mass of cross references. If, for instance, his lordship, Sepulchrave, the present Earl of Groan, had been three inches shorter, the costumes, gestures and even the routes would have differed from the ones described in the first tome, and from the enormous library, another volume would have had to have been chosen which would have applied. Had he been of a fair skin, or had he been heavier than he was, had his eyes been green, blue or brown instead of black, then, automatically another set of archaic regulations would have appeared this morning on the breakfast table. This complex system was understood in its entirety only by Sourdust — the technicalities demanding the devotion of a lifetime, though the sacred spirit of tradition implied by the daily manifestations was understood by all.

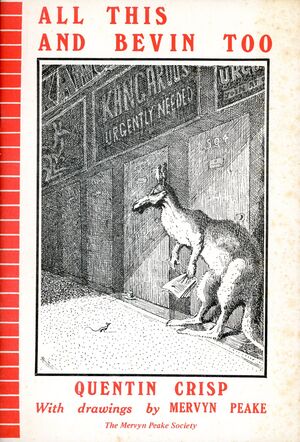

A painter and poet by training and trade, Peake brought his creation to life in vivid colors and descriptions. (He entered Belsen concentration camp on its liberation to make illustrations of it, which deeply affected him and the direction of Titus Alone.) Despite its Gothic unreality, Gormenghast always feels tyrannically real. Anthony Burgess called Peake’s writing “aggressively three-dimensional” and that’s rarely more apparent than in his delineations of the Groans’ domain.

The library of Gormenghast was situated in the castle’s Eastern wing which protruded like a narrow peninsula for a distance out of all proportion to the grey hinterland of buildings from which it grew. It was from about midway along this attenuated East wing that the Tower of Flints arose in scarred and lofty sovereignty over all the towers of Gormenghast.

At one time this Tower had formed the termination of the Eastern wing, but succeeding generations had added to it. On its further side the additions had begun a tradition and had created the precedent for Experiment, for many an ancestor of Lord Groan had given way to an architectural whim and made an incongruous addition. Some of these additions had not even continued the Easterly direction in which the original wing had started, for at several points the buildings veered off into curves or shot out at right angles before returning to continue the main trend of stone.

Most of these buildings had about them the rough-hewn and oppressive weight of masonry that characterised the main volume of Gormenghast, although they varied considerably in every other way, one having at its summit an enormous stone carving of a lion’s head, which held between its jaws the limp corpse of a man on whose body was chiselled the words: “‘He was an enemy of Groan'”; alongside this structure was a rectangular area of some length entirely filled with pillars set so closely together that it was difficult for a man to squeeze between them. Over them, at the height of about forty feet, was a perfectly flat roof of stone slabs blanketed with ivy. This structure could never have served any practical purpose, the closely packed forest of pillars with which it was entirely filled being of service only as an excellent place in which to enjoy a fantastic game of hide-and-seek.

And yet Gormenghast is not the greatest part of Titus Groan; that distinction belongs to the assorted cast of grotesques who inhabit the great stone citadel. None of the characters, save the infant Titus, is without some crotchet or oddity of feature. While Lord Sepulchrave is lost in despondency and only interested in his books, his wife, the Lady Gertrude, is like Gaia brought to life. She strides the castle titan-like, surrounded by the lapping waves of a sea of white cats. Birds come to her, nesting in her hair, feeding on crumbs held between her lips. Sepulchrave’s mentally impaired power-hungry sisters, Cora and Clarice, move and speak so similarly that, if hidden from view, it is impossible to tell which has spoken. The court physician, Dr. Prunesquallor, is given to constant high-pitched laughing and deliberate grandiloquence. Mr. Flay is tall and thin to the point of being skeletal.

Mr. Flay appeared to clutter up the doorway as he stood revealed, his arms folded, surveying the smaller man before him in an expressionless way. It did not look as though such a bony face as his could give normal utterance, but rather that instead of sounds, something more brittle, more ancient, something dryer would emerge, something perhaps more in the nature of a splinter or a fragment of stone. Nevertheless, the harsh lips parted. “It’s me,” he said, and took a step forward into the room, his knee joints cracking as he did so.

For all their peculiarities, the characters possess real vitality. Even with a satirical eye on them much of the time, Peake seemed incapable of portraying them without empathy. They are never mere mannequins upon which to hang an elaborate plot. When Flay, banished from Gormenghast, blossoms to life away from the strictures that have formed his entire life it is nothing but beautiful. You can feel the pressure of decades of obligation lifting from his soul. Prunesquallor, a seeming flibbertigibbet, is actually a deeply thoughtful and considerate man. His concern for Titus’ older sister, the daydreaming Fuschia, is real and touching as is her longing for any sort of relationship with her distant parents. Even Steerpike’s elaborate plotting springs from recognizable feelings of ambition and just defiance of a horrible, soul-crushing class hierarchy.

In a bravura section titled The Reveries, Peake exposes the inner workings of all the major characters’ minds. It provides a detailed snapshot of how each thinks as well as what is occupying their mind at the moment. The more reflective Dr. Prunesquallor and Lady Gertrude think of the future of Gormenghast while most of the others are concerned only with themselves and their present desires. Lord Sepulchrave thinks of comforting darkness and annihilation.

Titus Groan thrums with life because of Peake’s exquisitely Baroque prose. Some have condemned the book as slow-moving as if all that mattered was narrative pacing. What it is is deliberate. Peake carefully added each element, one by one, like the bricks of Gormenghast castle, in order to bring life to Titus Groan. What might appear sprawling and ramshackle is nothing of the sort. Each verbal filigree, each character, each chapter is potent and exactly where it belongs. The book’s final, powerful impact comes from the combined emotional weight of all those details coming together in a coherent whole.

I first read Titus Groan and Gormenghast twenty-two years ago. Every so often I was tempted to reread them, but I put it off each time. I think I had a slight fear that neither would remain true to the memories I had of them. This has proven utterly untrue. The books (I have already started Gormenghast) are even better now. That I missed out on earlier revisits to Peake’s world is a bitter realization. I suspect I will dream of Gormenghast’s alleys of stone, forgotten ballrooms, and hidden rooftop “fields of flagstones” forever. The smell of dust and tired liturgy will linger long past the turning of the last page. The hopelessness of Sepulchrave and the protectiveness of Flay and the good humor and humanity of Prunsequallor will endure in my consciousness. A fleet of white cats lining the top of a wall, the Tower of Flints and its owls, the ogreish Swelter, the one-legged Barquentine stomping angrily through the halls — these images will not be easily dismissed.

Why has Titus Groan not become the great popular fantasy novel it deserves to be? Anthony Burgess believed the British public was suspicious that Peake was too talented — I’m not sure exactly what he meant by that. Perhaps, he meant readers found the book in its length, its complexity, and the strangeness of its characters and setting, overwhelming. I can see how this might have been the case in the forties and fifties when fantasy literature was less popular although, alongside Gothic novels and authors such as Dickens, Peake really doesn’t seem that strange. With vast, immersive fantasy novels all the rage, it should be even less alien to readers today. Contemporary genre fantasy is given to meeting certain expectations. Here, there are no romantic couplings, no great heroics, no magic or fantastic monsters (only human ones). These elements are not missed, but maybe their absence is enough for many readers to discount it. The loss is theirs.

In 2000 a Gormenghast miniseries was filmed by the BBC. It covers both Titus Groan and Gormenghast. Except for the character of Steerpike, played by the far-too-handsome Jonathan Rhys Meyers, it is impeccably cast. Whatever attempts are made in the future (the rights have been bought and Neil Gaiman is attached), there can be no better casting than of Christopher Lee as Mr. Flay and Richard Griffiths as Swelter.

Unfortunately, the production is only average. The design is too medieval and elaborate for a proper portrayal of Titus Groan. There are far too many brightly colored CGI backgrounds and not nearly enough dust and despair. The novel is one of manners and atmosphere, both ofv v which are downplayed in favor of visual freakishness and humor. Still, it’s worth a look, if only to see the two actors above. At present, it’s available in four parts on YouTube and on BluRay.

PS: The title is lifted from Elizabeth Bowen

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Thanks, that’s a wonderful overview. The first two books are vast and tremendously rewarding.

They are also, I’d like to point out, great fun to read aloud, as long as you’re willing to take your time and let the words roll out at their own pace. In that way, Peake reminds me of Joyce.

I’ve never read the Gormenghast books. This piece is the first one to really interest me in doing so!

The trilogy is a unique, incomparable achievement, and I’m in the minority in considering the very different Titus Alone on a level with the first two books. (Lin Carter, I remember disliked it strongly.)

I’m sort of at a lost of words to describe my feelings about the trilogy. I would mention that it was not meant to be a trilogy, but a long series chronicling all of Titus’s life.

I think it might be the most beautifully written fantasy series there is.

Fetcher, what an epic article! These have been in my to-read pile forever. I had no idea about its history. Love these excerpts. Learned a lot. Am inspired. Thanks for doing this.

@Lawrence – I discovered, this time around, it does indeed sound wonderful read aloud.

@John – Read them, read them, read them.

@Thomas – I’m planning to read Titus Alone this time around. I was always put off, based on what I’d read about it, until discovering the older version is a terribly edited one that wasn’t fixed until after the Ballantine edition.

@Matthew – Ah, truly one of the great literary what ifs. They are indeed beautiful. I want to get my hands on his poetry

@Seth – You are welcome. Part of me felt the only thing to really do the book proper justice would have been to just list a dozen or more long quotes and leave it at that. Definitely give them ago. I assure you you will pick up the second volume the instant you put down the first

I read the first book around thirty years ago. I really enjoyed it, but didn’t read the second book until last year. I was curious to find out if my attitude towards Peake had changed in the interim. In fact, I enjoyed the second book as much as the first, with a few qualifications – Peake’s attempt at ‘humour’ fall pretty flat (Professor Bellgrove’s proposal being a case in point) but are luckily far and few between.*

I was in the fantasy section of a Dublin bookshop shortly before the pandemic, and it was interesting to see what fantasy and sf books of a certain vintage had survived the test of time. Gormenghast was one such book. So maybe more popular than one might think?

* Peake’s breakdown was precipitated by the failure of a play he had written. By all accounts this was another ill-advised attempt at ‘comedy’.

One of the best pieces I’ve read here at Black Gate, and an outstanding appreciation of a woefully underread series of books. I have the Ballantine paperbacks with the Bob Pepper covers, and I read all 3 books, one after the other, in 2009 when I was on sabbatical from my teaching job and free from grading papers. I thought the first book outstripped any other fantasy book I have ever read, before or since, and that includes Tolkien’s “Hobbit/LOTR” and the Harry Potter series. The second book was almost as good, but Peake was running low about halfway through, and I struggled mightily with “Titus Alone” and wondered what marvels the last 2 books would have been had Peake not suffered from his creative decline. Anthony Burgess’s assessment of Peake’s achievement as ‘aggressively three-dimensional’ is spot-on; I can think of few books that came to such vivid life for me as did “Titus Groan.” As a teacher, I learned to read quickly (albeit carefully) so as to get my grading done in a timely fashion (I tried to get all papers read & graded by the next class meeting), and that carried over into my reading for pleasure a little too often; “Titus Groan” wouldn’t let me do that, and I am grateful that the sabbatical gave me the time for leisurely reading to do justice to Peake’s exquisite prose. I bought the 1200-page omnibus version published by Overlook Press and gave it to my oldest daughter, who was a little too young at 14 to catch the full flavor of the first novel, and never went back to read the other two (yet). At 70, I’m more considerate of what I choose to read, not wanting to waste time on fluff or dreck if I can avoid it, but I do intend to revisit Gormenghast, and soon. Thanks, Fletcher, for an eloquent appraisal of a timeless masterpiece.

This is another of those that, like you, Fletcher, I last read 20+ years ago and keep thinking I should revisit. Maybe this will be the year?

Steerpike is one of the all-time great villains, right up there with the Vicar of Rerek, Horius Parry.

@Aonghus – I’ll have to see how it goes for me this time, but I remember chuckling at the Bellgrove/Prunesquallor romance

@smitty99 – Thank you for your incredibly kind words. It’s interesting but I’m right in a middle of rereading LOTR (for the umpteenth time since first picking them up 45 years ago), and, yeah, Peake is working on a very different plane than Tolkien. I say this with no intention of trying to diminish LOTR in any way, but Peake was doing something very different succeeded wildly. As I mentioned to Thomas above, Titus Alone existed in a butchered version prior to the seventies and many people feel the present edition is worthy of sitting alongside the first two books.

@Joe H – They’re definitely worth a revisit. As to the Vicar, I do hope to finally read some Eddison this year for this series.

You know I don’t know if I read the “butchered” version of Titus Alone or the “revised” version. I did consider it not as good as the previous books.

Yeah, when I originally read it I just read the first two books in the Ballantine paperback editions. When I reread it, it was the single-volume Overlook Press hardcover from the 90s or 00s and I assume it was the corrected text of Titus Alone? But either way, I didn’t like that volume nearly as much.

Fletcher, I don’t want to diminish Tolkien’s work, either. To the best of my knowledge, I have never encountered any hobbits or elves outside of the pages of fiction (I may have met a wizard once, who knew things he shouldn’t have, and I worked in the same department in a truck assembly factory back in the early ’70s with two guys I swear were orcs), but Tolkien’s characters have less of the human about them than Peake’s. By that I mean Tolkien gives us folks who are bigger than life, while in a weird way, I felt more — comfortable? — in Peake’s Gormenghast. Perhaps I’m trying to say that Peake’s world seemed more realistic to me, from a phantasmagorical point of view. Does that make any sense? I felt like I was inside Peake’s head, although it wasn’t what I would call serene or tranquil, in any sense (‘comfortable’ was not at all the right word), yet not quite foreboding. Maybe I’m going to have to go back to those books sooner than I intended.

Tolkien and Peake are utterly different animals, and are incapable of diminishing each other. (And necessarily demonstrate what a useless label “fantasy” is.) Who was the greater writer of the greater work? Proust or the anonymous writer of Beowulf? To even pose the question is to see its absurdity.

You are absolutely right, Thomas; we get caught up making comparisons and contrasts and end up trying to figure out if steak is better than pizza. Sometimes we just need to be grateful that writers like Peake and Tolkien have given us characters and worlds we are free to visit over and over and over again, and it doesn’t matter which work or writer is greater.

Wow, I echo those who commented before Fletcher, this has to be one if the best articles I have read in some time. I am also one of those who has been fence sitting in whether to read this series, well since I first saw them in a bookshop circa 1990. I think your article has toppled me off that proverbial fence for good.

Thanks also to the commeommentors such insightful comments that have if anything enhanced the overall appreciation of the core article

Tony, I envy you getting to read it for the first time!

I made the strategic reading “mistake” of taking on the whole Gormenghast series in the Ballantine edition with the lovely Bob Pepper covers, and then tackling the next item on my “TBR” pile, Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust. About 3 chapters in, I realized I was still reading Gormenghast! The level of sensuality of the prose by either Peake or Proust is remarkably high and detailed. “Mannered” is a great term for each! Thank you, Mr. Vredenburgh for putting that word back into my mind.