Half a Century of Reading Tolkien, Part Seven: The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks

Ten years ago to the month (I started this in October), I wrote about Terry Brooks’ groundbreaking The Sword of Shannara (1977), and declared that the joy I got reading the book the first time around was something I couldn’t recapture. Time had opened a gap between the book and what I could take away that seemed uncrossable. Revisiting the book, yet again, I no longer think that’s completely true, but it’s not entirely false.

Ten years ago to the month (I started this in October), I wrote about Terry Brooks’ groundbreaking The Sword of Shannara (1977), and declared that the joy I got reading the book the first time around was something I couldn’t recapture. Time had opened a gap between the book and what I could take away that seemed uncrossable. Revisiting the book, yet again, I no longer think that’s completely true, but it’s not entirely false.

When I set out earlier this year on my journey through Tolkien’s writing, I decided to mix it up with several works clearly inspired by Tolkien, and particularly the Lord of the Rings. Bored of the Rings (reviewed here), was my first choice because it’s an explicit parody of the trilogy (and a brilliant one!).

Sword was an easy choice, as well, even if its origin story is complex and was touched by divers hands (well, six, to be precise, between Brooks and the Del Reys). I’m not sure Brooks set out to write a story that tracks so closely to the LotR in so many places, but that was result. It kicked off the mass-market success of quest trilogies featuring secret heirs in search of the foozle needed to bring down the Dark Lord in his isolated redoubt.

My wife (and editor), was surprised I decided to reread Sword. Part of me agreed. I thought I’d said everything I could about the book last time around and I have dozens (HUNDREDS!) of books I should be reading, instead. Nonetheless, as I worked my way through The Hobbit and then Lord of the Rings, I kept having images from Sword pop up unbidden. Sometimes, they were in conversation with the Tolkien scenes that had to have inspired them, but not all. Some were wholly original to Brooks and I thought I might still find something in the book I’d found there nearly fifty years ago.

The last time around, I unloaded a ton of snark on Sword. Its deliberate creation in an effort to replicate the publishing success of Lord of the Rings at the hands of wily editor Lester Del Rey seemed an artistic atrocity.

In an interview from 2012, Terry Brooks lays it all out.

Yeah, that’s right. The prevailing opinion in the publishing industry was that fantasy was a niche genre and you could sell five or ten thousand copies of a good book, but that was it. Except for Tolkien, but that was Tolkien and he was gone anyway, so there was no point in fussing about that, and everything else that was out there just wasn’t bestseller material. And Lester thought this was a lot of hooey. I found all this out years later—at the time I’m sure I thought that he just had great judgment about my book. But he basically set out to take a Tolkien-esque kind of story, put it out there as a fantasy, and sell it in bestseller numbers. And that’s what he did with Sword. And he told me that I was going to take it on the chin over this from many, many sides, that people were going to hate it, that people were going to say it was a rip-off, that people were going to this, that, and the other thing.

Part of me is grudgingly grateful for the del Rey’s success at turning fantasy into a viable literary genre, but I think we’d all be much happier if Lin Carter had been the editor to achieve that. Carter’s opinion of Sword was made explicit in his survey of fantasy from 1977. He wrote that it is “the single most cold-blooded, complete rip-off of another book that I have ever read,” and “Brooks wasn’t trying to imitate Tolkien’s prose, just steal his story line and complete cast of characters, and did it with such clumsiness and so heavy-handedly, that he virtually rubbed your nose in it.” At the very least, we might have been spared the raft of Tolkien clones that weighed down bookstore shelves for two decades.

In contrast to del Rey, I have less of a grievance with Brooks. His response to del Rey’s warning above is incredibly honest.

And I said, “I don’t care. I want to get my foot in the door and figure out how I can do this for a living.” Because that’s what I wanted to do, I wanted to be a writer, and I had no clue how to go about doing it. Here was somebody whose work I respected saying, “I can make this happen,” so I did it.

He was a young lawyer with a dream of telling a story that mixed the swashbuckling stories of writers like Dumas and Scott with the “magic and fairy creatures” of Tolkien. It’s a wholly respectable goal and if it had been achieved it would have been a much better book. It never develops the full-throated brio of Dumas and company and it rarely finds any of the fantastical transcendence of Tolkien. Last time around, I wrote Sword “talks when it should at least be trying to sing,” and I stand by that. Still, I find myself a little fonder of the book than I was then.

Del Rey and Brooks set out to write a story of action and adventure that rolled ever, juggernaut-like, forward. After several chapters of vaguely-plotted events, Sword finds its way and reaches that goal. I became caught up in the escapades of the assorted characters. From the moment the band of incipient heroes arrive at the ruins of an ancient city and meet a cyborg monster, things never let up. You might recognize more than a few elements from Lord of the Rings — ring wraiths, a multi-walled city under siege, a dark lord in a dark land, etc. — but Brooks was a storyteller, even back then. I’ve read a fair number of the sequels to Sword and they never really sing, either, but they possess an almost irresistible pull.

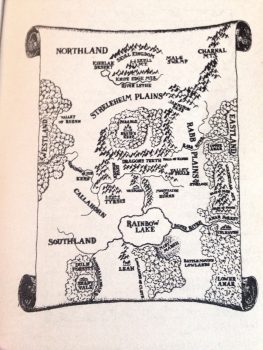

For those who’ve escaped this almost fifty-year old book, Sword tells of the quest of a doughty band of adventurers to recover the sword of Jerle Shannara, a long dead elf king. It was specifically forged to defeat the warlock lord, Brona. Centuries before the start of Sword, Jerle failed to kill Brona, only driving him into some sort of exile. Now he’s returned.

For the sword to work, it must be wielded by one of Jerle’s heirs. The only one remaining is Shea Ohmsford, an orphaned half elf living in the quiet town of Shady Vale alongside his foster brother Flick. Within a few pages of the first chapter, Shea meets the wandering Druid, Allanon (I’ll never not chuckle at that name) and learns he is in great danger and must seek flee his home and find refuge.

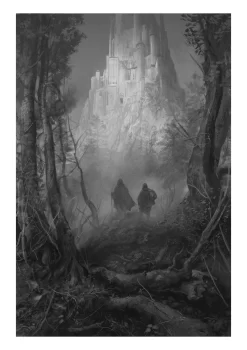

Before you can say Rivendell five times backwards, a party has been formed under Allanon’s leadership, consisting of the wizard, Shea and his brother, their friend, Prince Menion Leah, a dwarf named Hendel, another prince, Balinor Buckannah, and a pair of elven brothers, Durin and Dayel. For ages, the sword has been kept safe in the Druids’ tower, Paranor. On learning that it has been seized by Brona’s Gnome armies (gnomes are Shannara’s orc stand ins), Allanon plans a precision strike on the fortress to recover the sword before it can be moved. Alas, nothing goes as planned.

There are perils that must be overcome before Paranor can be entered. The first is an attack by an ancient killer cyborg. The cyborg attacks the party amidst the ruins of an ancient city.

Suddenly the road ended and the strange framework stood completely revealed, the great metal beams decaying with age, but still straight and seemingly as sturdy as the had been in ages past. They were part of a what had once been a large city built so long ago that no one recalled its existence, a city forgotten like the valley and the mountains in which it rested — a final monument to a civilization of vanished beings.

This description coupled with a few other passages in the book, make clear that Shannara is set long after an apocalyptic war. Trolls, dwarfs, and gnomes, we learned, are the results of assorted mutations (Elves were always there, but just in hiding). Later books in the series make it clear the setting is not just post-apocalyptic, but post-apocalyptic Earth. It remains the element of the book I still appreciate the most, even if it’s not as original as I once thought (I didn’t read Saberhagen’s Empire of the East until many years later).

The next great obstacle is a haunted tunnel under mountains that will allow the party to reach their destination in secret. It is filled with, well just the sort of things you’d expect it to be filled with.

Years ago, before the First War of the Races, a cult of men whose origins have been lost in time, served as priests for the gods of death. Within these caverns, they buried the monarchs of the four lands along with their families, servants, favorite possessions, and much of their wealth. The legend grew that only the dead could survive within these chambers, and only the priests were permitted to see that the dead rulers were interred. All others who entered were never seen again.

The assault on Paranor is a failure. Coming down out of the mountains from the Hall of Kings, Shea falls into a stream and is washed away. The sword has been spirited aways from the keep and

Allanon dies, seemingly, WHEN HE FALLS INTO A FIERY PIT FIGHTING A WINGED DEMON! Okay, there’re more than a few places someone should have been ashamed of allowing into print.

Escaping the keep and its gnome captors, the party members split up. Some go hunting for Shea and the others head toward the Balinor’s home city, Tyrsis, to warn of the impending invasion by Brona’s army of trolls and gnomes. Assorted familiar shenanigans ensue, including the appearance of a traitorous advisor and the siege of a great walled city built against a mountainside.

Shea’s adventure is easily the best part of the book. Captured by gnomes, he is rescued by a pike-handed, scarlet-garbed bandit named Panamon Creel and his companion, a troll named Keltset. Creel is in it, whatever it is, for the money, but in a Han Solo-sort-of way, and he turns out to be an ally of unsurpassed value. Keltset is a more mysterious figure, who emerges as the hero of his own story as Shannara races towards its end.

The trio’s march to the Warlock Lord’s tower is the most gripping and grim part of the book. As they cross the sere lands of Brona’s realm, Shea is tempted to madness. Nothing else in the book comes as close to having emotional weight.

Now, I’m going to spoil the ending, the ending of a nearly fifty-year old book. When Shea is finally confronted by Brona while wielding the sword, the first time I read the book, I expected some sort of brutal fight. Brooks is actually, for a rare moment, much more subtle. The power of the sword isn’t its ability to pierce a foes defenses. Instead, it forces whomever it touches to confront the truth about themselves. When he strikes the Warlock Lord with the blade, Shea perceives his true nature.

The touch of the Sword carried with it a truth that could not be denied by all the illusion and deceit of the Warlock Lord. It was truth against which he had no defense. For the Warlock Lord, the truth was death.

Brona’s mortal existence was only an illusion. Long ago, whatever means he had employed to extend his mortal life had failed him, and his body had died. Yet his obsessive conviction that he could not perish kept a part of him alive, and he sustained himself through the very sorcery that had driven him to madness….He was a lie that had existed and grown in the fears and doubts of mortal men, a lie he had created to hide the truth. But now that lie was exposed.

I loved that then and I love that now. There’s an element there of how the nature of fear and belief can shape the power of one’s enemies. It way too subtle for the book. Digging deeper into it is something Del Rey would have quashed with all his editorial power. Nonetheless, it points, if only a little bit, toward a better sort of storytelling.

In the past, I’ve described The Sword of Shannara as Lord of the Rings with training wheels, a book that talks when it should be trying to sing, a bereft of atmosphere. I think all those things hold true, and yet I won’t condemn the book as I once did.

It’s a fine enough young adult fantasy novel. That’s really what it is. Again hinting at what might have been, Brooks informs us that his original ending saw nearly every main character dead. Del Rey put the kibosh on that, at which point, Brooks realized, he should just write a book for all ages. That’s what he did, even if it does feel more like a rip off than just a pastiche of Tolkien.

What became clearer to me on this reading is that the book could have been the book Brooks’ notes in the annotated edition imply; a darker story, with more adult element and themes. One suspects the betrayals would have been more disturbing, the violence more graphic, and the casualties more devastating.

Once again, I will end by writing I don’t know if I’ll ever read The Sword of Shannara again. This time though, it’s not because I fear ruining some old memories. It’s because I’m nearly sixty and I don’t know if I’ll get around to it again. Besides, I’m a little curious about reading some of the sequels again, especially in the immediate aftermath of having reread Shannara. I’m really curious how Brooks’ writing and storytelling evolved. He would still be here almost fifty years later if he didn’t learn something over the decades.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I will always admit that one of the 4 books I ordered in my initial Science Fiction Book Club request was The Sword of Shannara, a book that I had already read courtesy of the public library. So I did like it, Tolkien pastiche that it may be (and progenitor of many more). I wonder if the final confrontation with Brona in Shannara provided inspiration to Stephen Donaldson, who climaxes his opening trilogy of Thomas Covenant, Unbeliever, with a similar resolution.

Besides Mr. del Rey’s perspicacity as an editor with an eye for the book market, I would also credit the concurrent breakout of Dungeons & Dragons that really helped fuel not only the fantasy boom of the 1980s, but very specifically the “Want more Tolkien” segment with its emphasis on parties of adventurers off on quests to thwart the Big Baddie. The stars were aligned, and we all know how that turns out!

And if I were picking a character from the book to play in an RPG, I would likely go for Panamon Creel.

Sure, D&D’s emergence had to have added to the genre’s success. It’s been a while since I read Thomas Covenant, so I’ll have to think about that.

Yeah, the similarity between Brooks & Donaldson is interesting. I don’t THINK it could be a direct influence, because I think both Sword and the full first Thomas Covenant trilogy both came out in 1977; maybe there was something in the water?

It’s now been even longer since I last read Sword than it was 10 years ago when I was commenting on your original post. My general attitude has softened considerably over the years, mostly by virtue of Terry Brooks being, by all accounts, a stand-up guy, so I can forgive some of those initial missteps.

I keep hoping Humble Bundle will offer a deal where I could just buy the entire series in eBook form for about $25 — that’s how I got my Kindle fully stocked with Wheel of Time and Drizzt books.

I also do remember the sequels (I only ever read the initial trilogy, so Elfstones and Wishsong) as being a major step up, not least because they weren’t so constrained by Tolkien.

The succeeding books were definitely more interesting. Part of me really wants to read the prequels that describe the aftermath of the apocalypse and the emergence of the various races and powers. Doubt I will, but I’d like to.

You know when I was younger I started a fantasy novel about the hero going on a quest with a dwarf, an elf and so on. Real original huh?

One thing I realized years later is that a lot of fantasy writers just use the same fantasy races over and over: Dwarves, elves, goblins. I began to wonder if we shouldn’t make up NEW races. I mean science fiction writers do so all the time. I’ve done this in some my short stories (some of which were published.) Having said that I seem to realize that new races may not have the same resonance as old ones, though.

Perhaps, instead of repurposing the same races/species, we should dig into the even older races of myth to fuel new fantasy. Greek, Norse, and Celtic myth have been mined pretty thoroughly, but there are countless races and creatures from Finnish, Persian, and Aborigine tales that could be the backbones of new adventuring parties, if so desired.

Charles Saunders, Milton Davis, and others have been working with African legends and themes/monsters/race for years now and it’s a great change of scenery

So, I think there’s some value to that. I definitely enjoy things like Vance’s Dying Earth series that has no recognizable folkloric ancestry. Or, like K. says below, work with other cultures and legends. In addition to his Omaro series, Charles Saunders actually produced the first volume of an epic trilogy with African-derived versions of elves and dwarves. Milton Davis and others have been working with African-inspired fantasy for years now, and some of it’s very good.

Can’t say that I’ve read anything Shannara (or if I did, I may have forgotten it), but I’ve very much enjoyed other works by Terry Brooks. If his work was as instrumental in kicking modern quest/journey fantasy into high gear as you say, I owe him a debt of gratitude. Can’t imagine what my reading life would have been without White’s Archives of Anthropos, Nix’s Old Kingdom series, or Britain’s Greenrider. All three are significant departures from the Tolkien formula, but it would have been terrible if editors had rejected them because of a bias against fantasy. Thanks for this informative retrospective.

(Off Topic: Did I see you over at the Journey Upstream stack? Or was that someone who stole your name?)

He (and the Del Reys) definitely bear responsibility, good and bad, for jumpingstarting modern fantasy fiction. I’ve always wanted to read Nix, but I’ve never heard of the other two. Definitely curious about Anthropos.

And, yes, you did see me at Journey Upstream (who would ever steal my name? I can’t even imagine that). I love the story and I think she’s creating some of the most beautiful comic art I’ve ever seen.

I only read Sword for the first time about seven or eight years ago; my reaction was pretty much, “Yeah…ok.” I don’t know that the book calls for more than that. I do think that you can feel Brooks’ love for LotR throughout, and that helps.

I know that the Del Reys and their influence are controversial topics. I haven’t read much of what resulted from their editorial policies, but I do know that the greatest fantasy books – The Well at the World’s End, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, Lud in the Mist, The Worm Ouroboros, The Circus of Doctor Lao, The Night Land, the Gormenghast books, The Lord of the Rings itself – were the products of eccentric, highly individual visions that came well before “fantasy” was even a publishing category. Just think how different from each other the books I mentioned are. I guess you could learn to dance via an Arthur Murray footprint-on-the-floor diagram, but you certainly can’t learn to fly with one…and real fantasy is flight. That’s what I think, anyway.

The pre-commercial fantasy is where my love for the genre lies. It was uncodified, eccentric, literary, inspired by the vast body of (mostly) Western myth and religion and not just previous fantasy novels. I’ve read plenty of LOTR-derived books, but few really rise above a fun read. The deeper, better reads come from books like the ones you mentioned (and I definitely need to write about Dr. Lao). Like I wrote, we’d be a lot better off if Lin Carter had filled the role the Del Reys held.

The Sword of Shannara, and Dungeons and Dragons, had more influence on my life-long love of fantasy than anything else. Tolkien, Moorcock, the Arduin Grimoire – there are a lot of early influences. But Sword fueled my teenage mind.

But Sword remains my single favorite fantasy novel.

I remain very disappointed that Brooks sold out and was part of that teen MTV series. Shannara deserves better. I’d go animated, myself.

And Lin Carter can go f*#@ himself for that snarky attack in one of his anthologies.

Yes, the MTV product was awful. I watched half an episode. Couldn’t help wondering if they had gotten all the actors from an Abercrombie & Fitch catalog – they were all so…..pretty. Gotta love the cast of gritty characters with perfect hair, smiles, and not a smudge of dirt. As for “Sword”, any fantasy book that had a map instantly became a possible setting for a homebrew D&D adventure.

Hey, we’re nice to Lin Carter here ;). Arduin is such a great, lunatic resource for any DM willing to run crazy adventures.

I think I might have made it thru half the first episode of the Shannara show. I still struggle to believe it was so bad.

I was in high school when this came out. I’d just started weaving out of the science fiction lane and into fantasy, having read “The Lord of the Ring,” “The Hobbit” and a smattering of Le Guin including the Earthsea trilogy and some short stories along with Carter’s history of fantasy.

I remember it being heavily promoted by the Science Fiction Book Club. I confess reading the synopsis and looking at the Hildebrant art and thinking that the Tolkien rip-off floodgates were opening, a feeling confirmed by the subsequent flood of fantasy trilogies within but a few years time. All of which subsequently killed my interest in fantasy for decades. The gross commercialization of the genre was bad enough but all of the books just looked so clumsily blatant.

In retrospect, I can’t imagine the book is much worse or more obviously pandering than most of what passes for epic fantasy these days. I can even confess to something like passing nostalgia for the days when this was featured front and center in the storefronts of mall bookstores at Christmas time way back in the seventies.

The book’s backstory made for an interesting read and at least shifts the bulk of the blame to del Rey. He clearly saw the genre as ripe for exploiting and while I don’t blame him for wanting to take advantage of a market trend he could have at least had enough integrity to not steer Brooks into something so transparently obvious, although a lot of readers certainly took the bait and kept coming back. Mencken and Barnum were proven right, yet again.

It’s better than many of its heirs and has some fine elements. I stopped reading fantasy for decades myself, or at least anything that resembled the commercial variety for pretty much the same reason. The little S&S renaissance of the past twenty years has produced some really exciting books, but, now the mainstream mostly mimics GRRM and that’s as bad as the days of the old Tolkien clones.

Thanks for the article, Fletcher. For me as an eighth grader, after deciding to venture into fantasy and reading “The Hobbit” I asked a friend to recommend a next read. He suggested “Sword” and I enjoyed it at the time. I wonder if it had anything to do with the colorful insert of the party – something that you didn’t see too often in non-children’s books. I confess that I tried to read “Fellowship” next and put it down because it was too slow (the topic of an earlier article). I went on to read any number of fantasy books of a variety of quality but never any more of the Shannara stuff. I had never heard the del Rey editing angle, thanks for telling that aspect.

Tolkien’s not for everybody, but then no book is. Yeah, the creation of Sword is fascinating as are the marketing tales recounted here in the comments. Thinking about it some more, does any run of the mill fantasy reader even know the names of any editors these days, ala’ Del Rey and Carter?

Derivative though the Shannara books may be, Brooks “Magic Kingdom For Sale-Sold!” remains a minor classic, imo. Subsequent books are not as good, but the first has a lot of charm. I presume this is because he was drawing more on personal experience in writing that, as opposed to a paint-by-numbers epic fantasy template

This is the only Brooks I have read. I enjoyed the first book as well. It’s a light beach reading kinda thing.

I read the second and third books and was bored enough I sold them and didn’t read the fourth

Edgewood dirk was the best part of the second, but I agree it wasn’t good enough for me to read the rest. I remember thinking that the first one was a perfect specimen of the sort of thing it was trying to be though

Your description of the first book being good and later ones more meh, reminds me of Christopher Stasheff’s The Warlock in Spite of Himself. That first book is a hoot, and all the later ones keep sliding downward in quality.

Diminishing returns on a premise is a sad reality (*looks at marvel*)

I read Sword of Shannara in the fifth grade and I believe it was the first novel of any heft that I ever finished. I was unaware of Tolkien at the time. I have so many deep memories of scenes from that book and, along with D&D, was very formative for my imagination. Seeing the illustrations from that book in this post are deeply nostalgic. While I eventually moved on to science fiction as my favorite genre (which has since expanded to all kinds of things in my old age), I have a lot of love for all the fantasy entertainment my friends and I got up to back in those days. Thinking about Sword of Shannara makes me remember what it was like to be 11 years old.

One thing I was surprised about was finding out that it was technically a post-apocalyptic Earth story. I never picked up on that when reading it, probably because at the time I had no concept of that genre and just assumed any passages related to that were just backstory for that world. I’m pretty sure I learned about this when the MTV show came out. And yes, I watched the entire first season for some reason. It was especially jarring when the adventurers discovered the underground high school, ancient football jerseys and posters (in remarkably good condition to boot).

Anyway, this was a very interesting article and I even went back to read the first one before finishing this one. Thank you for writing it. This is a fantastic blog and I really appreciate the writers here giving us solid content.

The second Shannara book, The Elfstones of Shannara, is a masterpiece. It’s always been my favorite of the series. In his writing memoir, Brooks says that that’s the book where he really learned how to write, and it shows. Lester del Rey actually rejected the first sequel Brooks wrote to Sword, saying someone else might publish it because of the success of Sword, but he wouldn’t, and Brooks said he learned how to write a book from going through the notes del Rey gave him on the unpublished second book, which eventually led to him writing The Elfstones of Shannara (which was also the basis for the TV show. They skipped Sword altogether).

(Also I think there’s a typo in the last sentence of the article. Shouldn’t it say “wouldn’t” instead of “would”?

I have residual fondness for the Sword of Shannara, in part because later books were substantively better but probably would have never existed without Sword, but also because there simply wasn’t enough out there in terms of this kind of high fantasy back then and we needed it. This book may have come out in 1977, but the Shannara series is very much of the 80’s, for all the good and bad of it.

For me, the post-apocalyptic aspects of it slipped past me when I first read this, and I think it’s one of those things that serves the story well when it’s done with a light touch, and the more they lean in on it the worse the story is for it. But YMMV.

Brooks is a big fan of the “assemble a party and go on a quest” kind of storytelling, and I have to say I enjoy it. Not everything has to so deeply complex and convoluted, not every villain has to “have a point”, and the leads don’t have to be deeply flawed and/or terrible people either. Sometimes there’s some joy in the purity of the good v. evil quest. There’s plenty of cliches to be found in Sword, but one of the reasons we see them that way is because of the work of Brooks over the years and so much of what followed in the 80’s and 90’s.

I have some real fondness for these early Shannara books. Paranor, Allanon, the Leah’s, and High Elven magic etc are all things I enjoy seeing and seeing more of. The more Brooks moved into original storytelling and away from grabbing chunks wholesale from JRRT (and let’s be honest: it’s still more original than what McKiernan did) the better it worked out, overall, but I still have fondness for Sword and it’s a solid example of this type of high fantasy.