Three Thousand (plus) Words of Longing: “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” and Three Thousand Years of Longing

Three Thousand Years of Longing (United Artists, 2022)

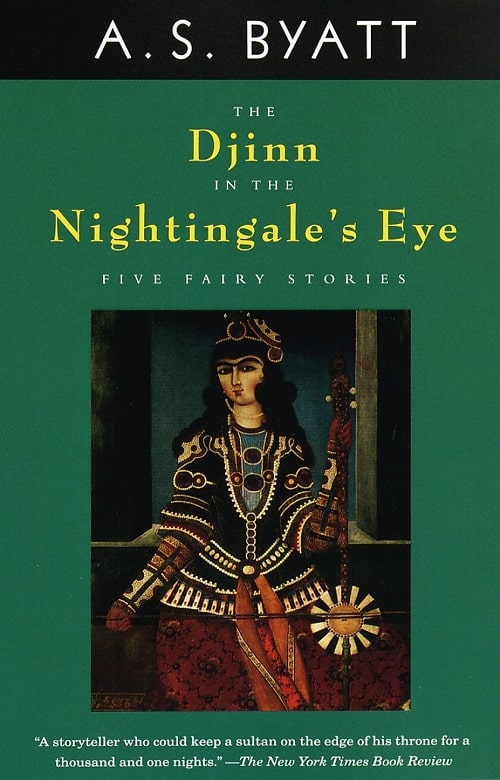

One of the leading fantasy movies of 2022 was Three Thousand Years of Longing, directed by George Miller of Mad Max fame, and starring Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba, who surely need no introduction. That might have been enough recommendation for me, but much more important was the source material, A. S. Byatt’s lovely novella “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye.” The novella was first published in the Paris Review in 1994, but I first read it in her collection also called The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye, from 1998.

One of the enduring questions people tend to ask is — “What was better, the book or the movie?” The real answer is – well, it’s so tempting to say “always the book” but that’s flip and just not always true! (Exhibit A, to be sure, being The Godfather.) Actually, the real answer is “They are different media, doing different things, and they can both be good in different ways.” Banal, maybe? — but still true. So I thought to look at my reactions to Three Thousand Years of Longing, and to “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye.” Which is better? Does it matter? Are they even directly comparable, or are they two different works of art, pleasing us in different ways?

[Click the images if you long for larger versions.]

|

|

The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye by A. S. Byatt (Knopf, October 27, 1998). Cover design by Andrea Pinnington

And, I have to say, I am going to come down on the side of the story. In rereading it (a few times) for this essay, it deepened. It gave the same pleasures it gave on original reading, and added more; and the meaning deepened for me. It is I think a great story, not just a very good one as I think I first thought, and I’m willing to place it with “Sugar” in the very top rank of Byatt’s oeuvre. As a result, I’ll end up taking a much closer look at the novella than the movie.

But let’s begin with the movie. Three Thousand Years of Longing opens with English narratologist Alithea Binnie (Tilda Swinton) attending a conference in Turkey. During her presentation, she sees a strange creature in the audience. And soon after, in a shop in Istanbul, she buys a strange old bottle. Obviously, this holds a djinn — and back in her hotel room, she accidentally releases it. The djinn (Idris Elba) appears, and after some convincing, and curious events like the djinn capturing an image of Albert Einstein from the TV, Alithea believes in the djinn’s reality. But she’s also sure that she shouldn’t ask for three wishes — because as a narratologist she knows such wishes usually don’t work out well.

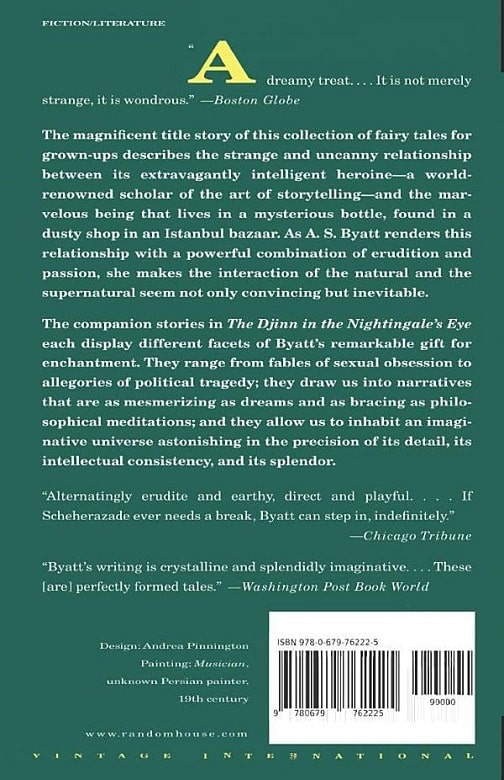

Instead, the djinn tells her a set of stories of his life — his brief periods of freedom between being trapped in a lamp or a bottle or whatever. The first story concerns the Queen of Sheba (played by the quite stunning Aamita Lagum), who, in this telling (and other traditional tellings), is part djinn, and is our djinn’s cousin and also lover. But then King Solomon (or Suleiman) comes to court her, and the Queen quite falls for him, making the djinn jealous. And Solomon, wise enough to perceive the djinn and to recognize his threat, imprisons him in a bottle. Millennia later, the djinn is freed by Gülten, a concubine of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She does use two wishes — to attract the attention of the Sultan’s son, Mustafa, and to bear him a son.

But she foolishly fails to wish for her own safety, and after she has Mustafa’s son’s child she attracts the attention of Hurrem Sultan (a real historical figure, also known as Roxelana, a Ruthenian (i.e. Ukrainian) woman who became Suleiman’s wife instead of concubine and had great power) — and such attention is dangerous. Soon Mustafa is killed in favor of Hurrem’s own son, and of course Gülten too is killed. The djinn cannot be freed, never having given Gülten her third wish; and he wanders the palace for a century, witnessing the fairly disastrous reigns of a couple of sultans, before one concubine finds him, and instead of freeing him wishes that he be trapped again.

The djinn’s third story is set in the 19th Century. His bottle is discovered by the young fourth wife of a prosperous merchant, who is relatively nice but still hardly a great husband, and of course the older wives are no friends of hers. She is a brilliant young woman, and when she realizes the nature of the djinn, she wishes for knowledge. They fall in love, and the djinn then resists asking her for a third wish, because he wants to stay with her. But she feels constrained, and wishes to forget him — and the djinn is imprisoned again. Only to be discovered by Alithea.

Inevitably, by story logic, they too fall in love, according to Alithea’s wish. When it is time for her to return to London, the djinn accompanies her. But in London he finds that the pervasive electronic radiation sickens him (for the movie, djinni are described as electromagnetic in nature to some degree), and Alithea realizes her wish that they fall in love was profoundly wrong. (There’s also a clumsy and rather pro forma bit about racist neighbors.) She wishes for his health to be restored, and for him to be free … And so he returns to the land of the Djinn. But his love was real … and from time to time he comes to visit.

And the novella? The overall arc is quite similar, but there are significant and important differences. To begin with, perhaps a minor difference: the main character’s name is Gillian Perholt. (I’m honestly confused as to why the name was changed for the movie.) Here’s the fabulous (in all ways) opening paragraph: “Once upon a time, when men and women hurled through the air on metal wings, when they wore webbed feet and walked on the bottom of the sea, learning the speech of whales and the songs of the dolphins, when pearly-fleshed and jeweled apparitions of Texan herdsmen and houris shimmered in the dusk on Nicaraguan hillsides, when folk in Norway and Tasmania in dead of winter could dream of fresh strawberries, dates, guavas and passion fruits and find them spread next morning on their tables, there was a woman who was largely irrelevant, and therefore happy.”

Gillian too is a narratologist, just divorced (her husband having left her for a younger woman of course, and split up with her by fax) and she is flying to Ankara for a conference. (Again, Byatt’s prose: “Two or three times a year she flew to strange cities, to China, Mexico and Japan, to Transylvania, Bogota and the South Seas, where narratologists gathered like starlings, parliaments of wise fowls, telling stories about stories.”) The theme is “Stories of Women’s Lives,” and Gillian’s paper is on “Patient Griselda” — that is, “The Clerk’s Tale,” from The Canterbury Tales. (As it happens, since first reading “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” a quarter century ago I have read The Canterbury Tales, so the story of Griselda is more familiar to me than it was then.)

Gillian narrates the story, and in so doing has a vision, of a ghoulish creature, a terrifying woman figure, for a moment she is frozen: “a pillar of salt, her voice echoed inside a glass box, a sad piping like a lost grasshopper in winter” — references to Lot’s wife and to Snow White (and Tithonus?) She comes to herself and then comments on the story. (“The Clerk’s Tale” is a story I enjoy and hate, because Griselda is treated truly awfully, and this is the substance of Gillian’s commentary.) Gillian’s also mentions Shakespeare’s late play A Winter’s Tale, which also tells of a woman unjustly assumed by her husband to be unfaithful.

Her friend Orhan also gives a talk — on the frame story behind the Thousand and One Nights — of why King Shahriyar had taken against women to the point of marrying a virgin each day and killing her that night. This concerns Shahriyar’s brother Shahmazan, who caught his wife with the kitchen boy and killed them, after which they discovered that Shahriyar’s wife was betraying him as well. They set out on a quest to find someone more unfortunate than them, and in the process are inveigled by the wife of a djinn into having sex with her — and so they decide the djinn is even more unfortunate than they, which, oddly enough, frees Shahriyar to go home and kill his wife and her lover and her slaves, and begin his revenge on all womankind. (As Orhan remarks, “It has to be admitted that misogyny is a driving force of pre-modern story collections.”) Orhan also tells the story of Prince Camaralzaman and Princess Budoor, in which a djinnayah (a female djinn) manages to unite two human lovers who had foresworn the company of the other sex.

These stories seem vital to me — each comes from a very important collection of tales. Each too is about men mistreating women, while expecting perfect faithfulness from them. The stories are both significantly “framed” in their original collection, and they are likewise framed in “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” — and quite explicitly told, narrated (as, again, they are explicitly narrated in their source collections.) And these stories are missing from the movie. But they point to themes essential to Byatt’s novella: the centrality of storytelling, and of point of view; sexual desire and abusive marriages, and also a key question: “What do women want?”

The stories continue. The entire story is made of stories. Gillian and Orhan head to Istanbul, and a mysterious tour guide tells her more stories, including one about Gilgamesh. (As ancient a story as we know.) There are visits to Izmir and Ephesus; to Hagia Sophia, where Gillian is induced to make a wish, and she asks to be invited to give a paper at another important conference in Toronto; and to the Grand Bazaar, where Gillian buys the small bottle called the “Nightingale’s Eye.” And then, back in her hotel room, while watching Boris Becker play tennis on TV, she opens the bottle and out comes the djinn. We are at the exact halfway point of the story. (And it is Becker, not Einstein, that the djinn holds in his hand, taken from the TV screen.)

Gillian, as in the movie, is chary of using her wishes, though she does make one request — that she get her 35-year-old body back, instead of her 55-year-old one. Then she asks the djinn to tell her about his captivity — the three times he ended up in the bottle. These stories are much as in the movies — about the Queen of Sheba (who challenges King Suleiman to tell her the secret of what women desire); then the Sultan Suleiman the Great, and his wife Roxelana (so the Djinn calls her), and her scheming and that of Gülten who had freed the Djinn, and the unfortunate successors of Suleiman, this episode ending when one woman wishes him sealed up in a bottle again; then finally about Zefir, the young wife of an old merchant, who wishes for wisdom and knowledge and falls in love with the djinn, who teaches her much and shows her wonders. Until they quarrel and he is imprisoned again.

Then he asks for Gillian’s story. Very little of Alithea’s personal story is related in the movie, but Gillian’s story is much more important to the novella. She says, “I am a teacher. In a university. I was married and now I am free.” And she goes on to tell him a few stories from her earlier life. One concerns a story she wrote at boarding school, and then burned. And: “When I was younger there was a boy who was real.” Not exactly an imaginary friend, but: “A golden boy who walked beside me wherever I went.” The djinn says he knows of such creatures, and that Zefir had such a friend. (And W. J. Turner’s once popular, now perhaps all but forgotten, poem “Romance” is quoted.) Finally the djinn asks for a story she has never told anyone, and she tells a horrible thing that happened when she was a bridesmaid, for a friend she thought very beautiful.

Her friend assures Gillian she is beautiful herself. And later the bride’s father comes into her room and sexually abuses her.

After this, the djinn asks Gillian to make a wish — and she wishes that the djinn will love her. This seems problematic — yet the djinn of course grants it, and hints that he is happy with it when she expresses guilt. He says, “You give and you bind, like all lovers.” They make love, and the next day head back to London. London is uncomfortable for the djinn — all the electronic traffic. She asks the djinn what he would wish for — and he mentions “the land of fire,” his native land, where the djinni live — but he doesn’t want to go there, because he loves her. Gillian gets her wish to give the keynote address, and at the conference, of course, she tells another story, of a poor fisherman who catches an ape that will give him anything he wishes for — with a snag. And the fisherman wisely asks for modest good fortune … and the snag is … unexpected, but apposite.

Gillian at last tells the djinn her third wish, and this wish is that the djinn make a wish. Which of course is to be free. The djinn reminds her that he still loves her … but he also needs to be free. The story continues: “And did she ever see him again, you may ask? Or that may not be the question uppermost in your mind, but it is the only one to which you will get an answer.” And of course she does see the djinn again, but what is the real question?

I don’t know the answer to that, and perhaps there is no one answer. My personal question was, to be sure, “What do women really want?” Does the story give an answer? Is it supposed to? Is it implied by Gillian’s earlier statement: “I was married and now I am free”? But what of the Queen of Sheba, who demands that King Suleiman find out what women really want, and when he does, consents to marry him?

As I’ve said already, I love the story “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye,” and only rather like the movie Three Thousand Years of Longing. And why is that? The outlines of the two stories are much the same, and one final conclusion — that Alithea/Gillian’s final wish must be to let the djinn choose his freedom — is largely the same. Indeed it can’t really be said that the movie violates the spirit of the story, or betrays it. (And to be fair to movies — they are NOT required to tell the same story as their source material, nor even to agree with it.) But when I set the movie next to the story, what I see is that the story is much richer, much fuller. I also see that it is much slyer. And much more ambiguous.

A key part of the novella is the emphasis on story. The movie essentially tells us just three stories — the djinn’s three. (Not counting the overall narrative, of course.) The novella tells many more — Gillian’s versions of several old stories, Orhan’s version of a couple of Arabian Nights tales, Gillian’s stories of her childhood, and others — the museum guide’s tale, for instance. (It should be noted that we do see mentions of some of Alithea’s life events in the movie.) In many ways I think the novella is about how we define ourselves through story. What the stories we like tell about us. Or rather, what the stories we tell tell about us — especially the way we tell our own stories. The voices of both Gillian and the djinn as they tell their stories are critical, as well as the framing of the stories. Much of the story is frames, and frames within frames, as I’ve already hinted.

After all, to quote Byatt from the first page of the novella, narratologists (like Gillian Perholt) tell “stories about stories.” Thus, slyly, she has already told us that “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” is a story about stories. And if the story is about story, then; surely the stories hint at answers to our questions about what Byatt means. For stories about stories are also stories about people, and stories about life.

Look at all the stories within this story: “The Clerk’s Tale,” A Winter’s Tale, Scheherezade, Prince Camaralzaman and Princess Budoor, Gilgamesh, the Djinn’s three stories, Gillian’s stories from her youth: the Golden Boy she wrote stories about, and her abuse at the hands of her friend’s father; the old old story of Gillian’s husband leaving her for a younger woman, and Gillian’s story about the fisherman, the apes, and the three wishes. Most of these stories are about men and women, and many are about marriage. The other recurring theme is wishes. Gillian’s paper in Toronto is called “Wish-Fulfillment and Narrative Fate: Some Aspects of Wish-Fulfillment as a Narrative Device.” This is funny itself as it is clearly a sly comment on the very story it appears in. But it does remind us to look at wishes.

What, then, do the various stories say about men, women, and marriage? It’s easy to point to the fact that in most of the stories, the men in marriages are terrible to their wives. Walter in “The Clerk’s Tale,” Leontes in A Winter’s Tale, King Shahriyar and his brother Shahzaman, the 19th Century Turkish man — all are variously awful, and sometimes murderous. King Solomon is a more ambiguous figure. The stories from the era of Suleiman the Magnificent are more focused on the women in the harem, but clearly their unequal state compared to that of the sultans affects them cruelly. Gillian’s husband is a coward and cheater, her friend’s father is an abuser. Perhaps the one “good” husband is the fisherman in the story of the apes (and, just possibly, Prince Camaralzaman though we know nothing of his life after marriage.)

Sexual desire, on the other hand, is presented as worthwhile, even if it complicates women’s lives immensely (and sometimes leads to bad ends.) Indeed, we might ask if sexual desire is analogous to wishes — if you aren’t careful, it will turn against you. The Queen of Sheba feels intense desire for King Solomon, and the djinn warns her that this will cost her her freedom. The desire of Gülten for Mustafa dooms her. Gillian’s own desire for the djinn seems to lead her a bit, though not fatally, astray. The story also references female goddesses associated with sexuality: Cybele, Astarte, and most notably Ishtar and Diana of Ephesus. Ishtar, in the story of Gilgamesh, murders Gilgamesh’s bosom friend Enkidu. Perhaps the statement here is about power imbalances in sexual relationships.

On to wishes. How many wishes are there? Gillian wishes to have her 35-year-old body back, to have the djinn love her, to be invited as a keynote speaker to the conference in Toronto, and to have the djinn make his own wish. Gülten wishes for Mustafa to love her, and for herself to become pregnant. Another harem woman wishes for the djinn to be again imprisoned. Zefir wishes for knowledge, and to fly to the Americas, and finally to forget the djinn’s existence. The fisherman wishes for a good life but a modest one, the sort of life he could plausibly have made for himself with some good fortune.

And finally he realizes that his wishes take a toll on the ape that grants them — and he too sets his wish granter free. Thus, indeed, the message seems to be a meliorist one — wishes have costs, and the costs of grand wishes will usually redound on the wisher, while even modest wishes can hurt the giver. Perhaps there is a sort of conservation of wish energy?

What do women want? What do djinns want? Or apes? Or men? They all have desires. And those desires can warp lives, not just theirs but those around them, especially in the case of great inequality of power. So what should women want? My best thoughts may seem a bit pat, but perhaps simply independence is the answer. (And the same for djinns.) And to achieve what your nature will reasonably allow you: as it might be, a 35-year-old body (but not eighteen years old!)

Or prominence, through enjoyable work, in whatever field you choose. (It is notable that Zefir, wishing for knowledge, earns it on her own, with the djinn simply making books available to her.) Sexual satisfaction, or just companionship, on equitable terms with someone who enjoys that too. And, perhaps most of all, a full life, from beginning to end. “A woman’s life runs from wedding to childbirth to nothing in a twinkling of an eye,” says Gillian in discussing Griselda. And what she wants is to avoid that “nothing,” to be more than just a bride and a mother.

And, hey, perhaps I am way off base here. But it was immensely enjoyable to arrive at this point. And here too is a reason that for me the novella is better than the movie. It’s not just that the story’s message is more complex — the movie truly seems to focus on one goal, a noble enough one: the freedom of the djinn. The story gives equal or greater weight to Gillian’s needs, and thus inevitably to human nature.

Beyond that though, the story is suffused with pleasure. The prose is glorious. And the story, on rereading, reveals connections between its narrative subtly laced through from beginning to end. Movies don’t have prose to rely on, to be sure (though there is dialogue.) But they do have images, and it must be said that Three Thousand Years of Longing is a beautiful movie. But I don’t think that that beauty is as original, or as meaningful, as that of the prose of “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye.”

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a review of Being Michael Swanwick by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

OK, I did like the movie quite a bit and now I’m convinced I need to read the original.

“What was better, the book or the movie?”

I used to believe that the book always trumped the film, until I noticed how I preferred whichever version I saw first. I guess this just proves the primacy of storytelling over the medium used – ie, the first time you hear a story is when it’s likely to have the most impact on you.

Each too is about men mistreating women, while expecting perfect faithfulness from them.

Interesting to note that the central premise reverses this to some degree – ie, if you define the djinn as male, then he’s essentially a slave, the property of each of his female owners.

That’s quite true! — the djinn is indeed enslaved by his female owners.

Is he a he? Well, one of the stories told in the novella explicitly mentions female djinni, so I suppose they were (in that case at least) gendered.

Does anyone know where the idea of “freeing” a djinn/genie came from? When I was a kid in the ’80s, I don’t recall this being a thing–the purpose of a genie was to grant wishes, and genies weren’t generally presupposed to have a separate existence from that purpose. Then of all places, DuckTales The Movie in 1990 had a plot involving a genie who wanted to be freed, and then Disney’s Aladdin two years later brought the idea to a global audience, and it seems to have taken off since then, fueled as well by societal ideas about freedom and social justice. But are there earlier versions?

It seems to have its origin in “The Fisherman and the Jinni,” the second top-level story in the Thousand and One Nights

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fisherman_and_the_Jinni

There, the originally angry genie/jinni/djinn so embittered by his long imprisonment that he intends to tear whomever frees him to tatters, but is tricked into reentering the lamp and agrees to grant a wish as a condition of his release (and to not harm the fisherman).

I’m not sure when this first morphed into three wishes, but the earliest famous 20th century version of that motif is the 1940 film The Thief of Baghdad, in which the genie agrees to grant Ahbu three wishes if the young thief releases him from the lamp. After granting the third wish, the genie is free to depart to his realm (traditionally, the Land of Fire).

There are actually two genies in The Tale of Aladdin, the Slave of the Ring and the Slave of the Lamp. Both are bound to those objects, and both grant an unlimited number of wishes to whomever owns the ring or lamp, with no conditions.

The Jinn as a concept pre-exist the notion of a magic lamp etc – they feature in the Koran, are powerful spirits etc, so one can see why the idea of having one trapped in a vessel of some sort might be so appealing. Also why they might resent it – in The Thief of Baghdad (circa 1940) a jinn is so furious at his lengthy imprisonment he wants to kill the boy who released him. He’s tricked into granting the boy three wishes instead, which might explain where the whole notion of three wishes started.

I never understood why the Jinn was compelled to return to its prison after granting each wish – ie, makes more sense if you only agree to let it out on the condition it grants your wish (or wishes).