Fantasia 2021, Part LVIII: Stop-motion madness — Junk Head redux and Mad God

I’ve generally been reviewing one movie a day as I work through my experience of the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival, but today I’m doing something a little different. One of the movies available on-demand this year was a reworked version of Junk Head, which I reviewed when it played Fantasia in 2017. Another movie at this year’s festival was Mad God, the brainchild of veteran special-effects man Phil Tippett (who worked on the original Star Wars trilogy, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Robocop, and a lot of other things). Both are works of stop-motion wizardry; both involve stories of explorers from a realm above descending into a world of darkness and pain. And both have religious themes in mind. I decided to watch the new edit of Junk Head, follow it with Mad God, and then write about the first movie briefly as a way to in to the second.

I’ve generally been reviewing one movie a day as I work through my experience of the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival, but today I’m doing something a little different. One of the movies available on-demand this year was a reworked version of Junk Head, which I reviewed when it played Fantasia in 2017. Another movie at this year’s festival was Mad God, the brainchild of veteran special-effects man Phil Tippett (who worked on the original Star Wars trilogy, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Robocop, and a lot of other things). Both are works of stop-motion wizardry; both involve stories of explorers from a realm above descending into a world of darkness and pain. And both have religious themes in mind. I decided to watch the new edit of Junk Head, follow it with Mad God, and then write about the first movie briefly as a way to in to the second.

Junk Head is fundamentally the same movie as it was in 2017, and much of what I wrote then still applies. It’s the creation of Takahide Hori, who wrote and directed and edited and did the cinematography and the animation, and it’s a science-fiction story with elements of horror. In the far future, human beings live atop skyscrapers like gods but are threatened by a plague. One human descends into the lower levels of the world, long since abandoned to mutated clones, seeking the secret to defeat the illness. Things do not go as planned.

It’s a little difficult to draw distinctions between the previous version of the film and the current one, in that it’s been four years since I saw it and the movie’s not greatly reworked. About ten minutes have been edited out, but I don’t think much new has been brought in. It seems to me that there’s less backstory introduced up front, while an ending I thought was unclear remains so. On the other hand, connections between parts of the movie are more obvious, whether because of the re-editing or just because I’m approaching it for the second time.

It’s a little difficult to draw distinctions between the previous version of the film and the current one, in that it’s been four years since I saw it and the movie’s not greatly reworked. About ten minutes have been edited out, but I don’t think much new has been brought in. It seems to me that there’s less backstory introduced up front, while an ending I thought was unclear remains so. On the other hand, connections between parts of the movie are more obvious, whether because of the re-editing or just because I’m approaching it for the second time.

There’s less of an element of horror, though again familiarity may be a factor. The unnamed human still wanders through a brutalist nightmare of concrete corridors, a sprawling maze here and there interrupted by massive chasms or vast vaulted chambers or complex masses of furnace pipes. The creatures he finds are still deeply unsettling, made of elements of the human form recombined in deeply inhuman ways. And the movie’s still worth seeing for the visuals alone, a spectacular vision of a future divided between the godlike immortals above and the hellish realms below in which the story’s set.

There has to be a considerable discipline involved in cutting material from this story, given the labour-intensive process of making the film. It’s labour that pays off, but there must be a special tough-mindedness required to cut out bits of it. Overall I think the edit’s better (in comparison to my four-year-old memories, at least). It strikes me as smoother and clearer, easier to follow. All the visual moments that remained n my memory from 2017, and there were a lot of them, are still here. I might argue that the original version felt a bit bigger, but I don’t know whether that’s just a function of encountering the film for the first time.

There has to be a considerable discipline involved in cutting material from this story, given the labour-intensive process of making the film. It’s labour that pays off, but there must be a special tough-mindedness required to cut out bits of it. Overall I think the edit’s better (in comparison to my four-year-old memories, at least). It strikes me as smoother and clearer, easier to follow. All the visual moments that remained n my memory from 2017, and there were a lot of them, are still here. I might argue that the original version felt a bit bigger, but I don’t know whether that’s just a function of encountering the film for the first time.

Watching it the second time, I was struck by the intelligence of the backstory. Setting the film in endless Morlock tunnels of the future creates a background perfect for stop-motion; visually interesting but entirely man-made, interiors opening into interiors, locations that can be built and manipulated without worries about appearing artificial — the point of the place is specifically that it’s artificial. And the overtones of religious themes, of a future god descending into a hell that’s grown up beneath his feet, makes for an interesting flavour. It’s not insisted on, but there is some meeting of the higher and lower worlds by the end of the film, food for thought even as the story promises to go on. It’s an incredible movie, and in both its old and new forms a powerful achievement.

Before turning to Mad God I watched a short bundled alongside it, “Worse Than the Demon,” a 13-minute making-of documentary directed by Phil Tippett’s daughter Maya. It chronicles the journey to making Mad God, starting literally decades ago. For 35 years Tippett would tinker with the film, adding a bit here and a bit there, sticking to practical effects and stop-motion even as CGI revolutionised the field of visual effects. “I make stuff because it pleases me,” Tippett observes, and we see a bit of his workshop, a bit of his process, a bit of the physical labour involved in his acts of creation. The short’s a useful companion to the feature, and does what it wants to do in establishing the scale of the work involved in making the 83-minute feature.

Before turning to Mad God I watched a short bundled alongside it, “Worse Than the Demon,” a 13-minute making-of documentary directed by Phil Tippett’s daughter Maya. It chronicles the journey to making Mad God, starting literally decades ago. For 35 years Tippett would tinker with the film, adding a bit here and a bit there, sticking to practical effects and stop-motion even as CGI revolutionised the field of visual effects. “I make stuff because it pleases me,” Tippett observes, and we see a bit of his workshop, a bit of his process, a bit of the physical labour involved in his acts of creation. The short’s a useful companion to the feature, and does what it wants to do in establishing the scale of the work involved in making the 83-minute feature.

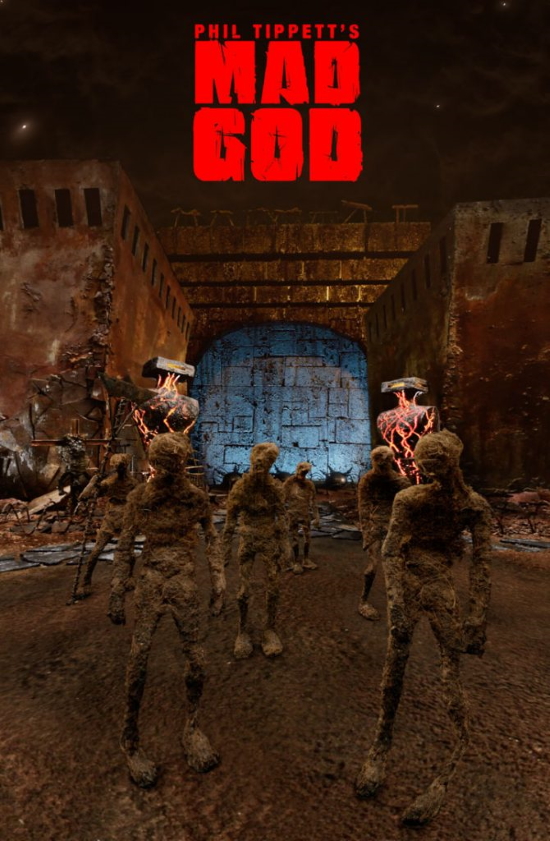

Mad God was written and directed by Tippett, and it’s definitely a singular vision, of the kind you rarely get with this level of resources. The plot begins with a figure in a head-to-toe uniform like something out of World War One, descending into a world of monsters and violence to follow a crumbling map to an unsure destination. There is little dialogue in the film, and none as we follow this solitary figure and see what happens to him. The result of his quest sets up an extended flashback, and then we get a third section to the film in which two monstrous figures enact a weird process to get a vision of creation and why the world is as it is. Meanwhile, we’ve seen the figure who dispatched the original quester, and seen the forces threatening him, and the importance of the quest.

It took me two viewings to even begin to assimilate the plot. Partly — mainly — that’s because the plot is not really the most important thing in this movie. It’s a series of sequences and images, each unfolding out of each other like nightmares. The world through which the quester journeys is a series of tableaux in which monstrous forms do monstrous things, filled with images of bound and suffering entities. The details of the images and how they’re all related to each other is less important than the total effect. This is a movie about texture and resonance.

It opens with a particularly bloody quote from Leviticus, establishing the film’s idea of divinity. We are, I think, encouraged to see the worlds through which the quester journeys as a hell indistinguishable from Earth. The final cosmic vision of history at the end of the film seems to me to confirm this; but I could be wrong. As I say, sensory overload sets in over the course of the film.

And in fact Tippett’s less concerned with getting across a clear story than with the individual sequences and all their nightmare imagery. I can think of a number of ways the extended flashback we see to an earlier quester might be integrated into the overall narrative, but even after two viewings I can’t say if any of them are right. I have some ideas how the figures who dominate the end of the movie, an alchemist gnome and a gigantic shape in a plague-doctor mask, relate to earlier elements of the film. But I could be wrong.

And in fact Tippett’s less concerned with getting across a clear story than with the individual sequences and all their nightmare imagery. I can think of a number of ways the extended flashback we see to an earlier quester might be integrated into the overall narrative, but even after two viewings I can’t say if any of them are right. I have some ideas how the figures who dominate the end of the movie, an alchemist gnome and a gigantic shape in a plague-doctor mask, relate to earlier elements of the film. But I could be wrong.

The movie’s success is that you don’t care about these details. It’s the twenty-first century; if you really want to know, you can probably find theories on a fan forum somewhere. The important thing is that the movie holds us from moment to moment, even without the standard appurtenances of story: with only rudimentary characters, and only the most basic sense of a quest structure. I found it did this. Others might not, particularly viewers who have a limited taste for violence and brutality; reports from the film’s premiere in theatres in Locarno had members of the audience walking out with anxiety attacks.

That’s easily understandable. The movie’s filled with grotesquerie: giants in electric chairs, monkeys subjected to vivisection, senile graeae passing their single eye back and forth, zombie workers under a steamroller, a worm cut out of a human (or humanlike) being. There’s an overall sense of the wars of the early twentieth century, bombed-out cities, barbed wire, massive machines of uncertain purpose. Shit and blood and bullying. And always images of a rolling bloodshot eye, recurring again and again, eyes that see only madness and murder everywhere they turn, eyes that cannot stop seeing.

The colours are vivid, even lurid. There’s something unnatural to them, as though even when we see the sky we see it through an atmosphere polluted with gunpowder and greenhouse gasses. The visual effect’s powerful; everything’s unreal and more than real, shadowed and yet lit with eerie precision.

Through this stop-motion world we watch our protagonist journey, just as uncaring gods would watch tiny humans. There are references to a number of movies in Mad God, to the point where I wondered if there was some repudiation of Tippett’s previous work here, an implication that the film audience is the collective mad god with a sadistic taste for the torture of the characters they watch. There is certainlly a sense of bondage constant in the film, creatures strapped down, creatures in slavery, creatures toiling for the glory of an uncaring higher power.

Through this stop-motion world we watch our protagonist journey, just as uncaring gods would watch tiny humans. There are references to a number of movies in Mad God, to the point where I wondered if there was some repudiation of Tippett’s previous work here, an implication that the film audience is the collective mad god with a sadistic taste for the torture of the characters they watch. There is certainlly a sense of bondage constant in the film, creatures strapped down, creatures in slavery, creatures toiling for the glory of an uncaring higher power.

Paradoxically, there is also a cosmic scope. Among the references to earlier movies is a certain black monolithic shape that emerges most powerfully in the final vision of the film; there’s a sense of cycles of history, a sense of the world as a theater of cruelty that one can nevertheless look beyond. It may be that the idea of a potential relief from the horrors of the world is meant as illusion or mockery, though. Certainly the characters who produce it are not necessarily sympathetic. And the figure who set the original quester in motion ends the movie in a dubious position.

Mad God is an extended dieselpunk nightmare that’s difficult to assimilate. My experience was that watching it one time left me with a tremendous respect for the craft of the movie, a sense of the power of Tippett’s vision, a respect for the creativity that engineered all the scenes of suffering and cruelty, and only a hazy sense of the story outline. A second viewing a couple of days later gave me (what I think is) a better understanding of the story, particularly in the last half-hour or so. On my first viewing I had, without really being aware of it, been overwhelmed by al the things I’d seen. It didn’t help, I think, that past a certain point Tippett’s telling his story in unconventional ways — the character whose point-of-view we follow for the first half or more of the movie gives way to other things. The second go-round made the connections between parts of the film clearer.

It also suggested a few possibilities for how to see things which might or might not be accurate; maybe a third viewing would confirm or deny them. But maybe it wouldn’t, and probably it wouldn’t matter. Even with the dreamlike story the vision of the film is powerful, a constant well of creativity and techno-horror imagery. There’s something profoundly mythic in this film, something that works even when it’s difficult to understand rationally. Or, to put it another way, something that many will find tempting to dismiss as excessive and over-the-top. I don’t think it is; I think it’s something desperately worth seeing, if you’re prepared to accept what you’re watching. If so, and if you’re in a mood to honestly grapple with the weirdness of the film, then there’s a power here quite unlike anything else.

And, finally, seeing Mad God alongside Junk Head (or vice versa, if you prefer) I think helped both films. Specifically, it pointed out how distinct the visions of both movies are. They’re superficially similar in the general story set-up, but unfold in wildly different ways, with different tones and different visual sensibilities. They’re both excellent movies, both clearly the product of intense work. When you see them together you see how individual they are — even things vaguely like them are completely different. Junk Head is dark, but optimistic; Mad God is unyielding, if baffling. Both are deeply powerful.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.