Fantasia 2021, Part XLIII: Stanleyville

“Anita McNelson,” written and directed by Canadian Luke Whitmore, is a 15-minute suspense film about an elderly woman who finds hints that her husband is having an affair. It’s nicely shot, apparently a period film, and unfurls with minimal dialogue. It’s effective because it gets across not just the emotional situation of the characters but also a history that shapes their present situation and actions. The story’s simple but effective, though at one point it apparently depends on a conveniently-open door; and it has a final sting that at least borders on the gratuitous, as though Whitmore didn’t trust the strength of the rest of the short and had to provide a cute little bow. It’s unnecessary, because the rest of the film does work just fine.

“Anita McNelson,” written and directed by Canadian Luke Whitmore, is a 15-minute suspense film about an elderly woman who finds hints that her husband is having an affair. It’s nicely shot, apparently a period film, and unfurls with minimal dialogue. It’s effective because it gets across not just the emotional situation of the characters but also a history that shapes their present situation and actions. The story’s simple but effective, though at one point it apparently depends on a conveniently-open door; and it has a final sting that at least borders on the gratuitous, as though Whitmore didn’t trust the strength of the rest of the short and had to provide a cute little bow. It’s unnecessary, because the rest of the film does work just fine.

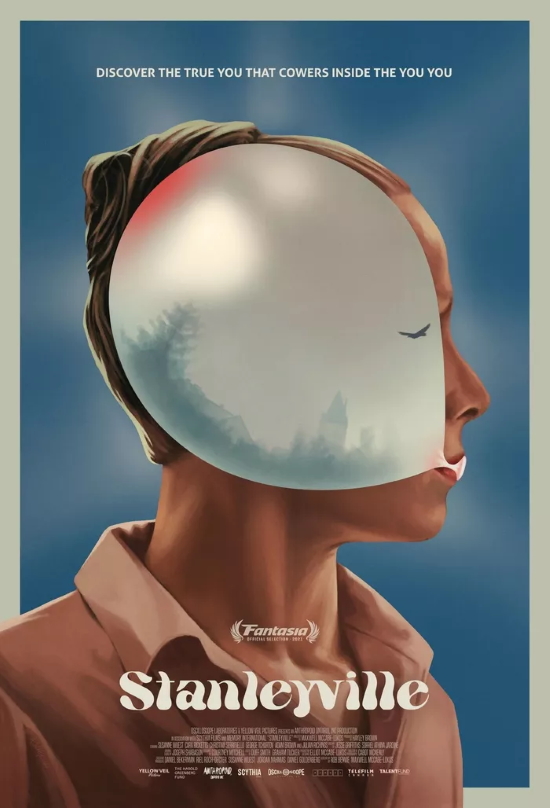

Bundled with it was Stanleyville, a feature-length satire directed by Canadian character actor and filmmaker Maxwell McCabe-Lokos, who co-wrote with Rob Benvie. It’s his debut feature film (after three shorts), and he drew an interesting cast, notably including Julian Richings (whose extensive body of work includes last year’s Anything For Jackson as well as 2014’s Patch Town). In a question-and-answer period (available, as usual, on Fantasia’s YouTube page) Richings talked about how McCabe-Lokos’ background as a character actor informed the structure and craft in the script, which puts a set of quirky characters in a room together and sets them at each others’ throats. You can see that craft, and what comes out of the performances; how the story hits may depend more on the viewer.

The film begins with Maria (Susanne Wuest), an office worker with a family, who one day at the mall is met by a stranger (Richings) who gives her the chance to throw that life away to take part in a contest. She’ll be locked up with four other people, and they will be given a series of contests, and the one who wins the most contests will win authentic personal transcendence. And also a new SUV. The other four people are each deeply strange, but so are the contests they’re given — blow up and pop as many balloons as they can in one minute, or write a new national anthem, or build a telecommunications device. Some of the other contestants will stop at nothing. And it looks as though whoever’s behind the game is making things up as they go. And then the contestants make contact with a voice beyond the room, and there are mysteries there as well.

In fact this is a film that doesn’t aim at realism. The cartoonish, caricatural nature of the characters is obvious, but the further the film goes on the more we see that the plot and structure’s a caricature as well. And there’s not much of a concern for internal logic in the sense of developing a bigger picture. The decisions the characters make are usually grounded in dramatic arcs, or at least consistent backgrounds, that have been set up and developed. But plot questions like ‘who or what is behind the game,’ and ‘who or what is mysterious voice that gives them advice over the radio’ are left untouched. Add in an equivocal ending, and there is a sense that symbolism is doing the kind of load-bearing work that plot usually handles in most movies.

This works to a point. The characters are watchable individually and as a group, once one accepts that they’re cartoons. In that sense, Cara Ricketts’ conniving amoral double-dealer is perhaps a bit out of place; the other characters have some peculiar thing in their background — an equivocal family heritage, commitment to a pyramid scheme, delusions of future stardom — but Ricketts is given a character without those kinds of links to other people. So while all the performers play their characters as basically real within a cartoony reality, Ricketts doesn’t get the same kind of cartoony background. Which means that there’s a sense of something almost unfair as she sets about winning.

That inconsistency of tone struck me because I found myself wrong-footed by the movie quite a bit. There’s a considerable amount of cleverness in its set-up, but little clear comedy. There’s a strong satirical and absurdist tone, but not much sense of anything in particular being satirised — you could say modern consumerist society and the drive for success at all costs is the focus of satire, but then you could also say that the drive for individual transcendence is also being satirised at the same time. It might be meant as a tongue-in-cheek look at one person’s internal voices, but most of the characters don’t clearly represent an obvious drive. And then some elements, such as the voice on the radio, simply feel unmotivated or unclear in their meaning. (I note that while watching the movie I interpreted that voice as probably satanic or infernal, while McCabe-Lokos noted in the q-and-a that his idea was that it represents the primitive id; there are similarities between my take and his intent, but there’s enough of a difference, particularly in a movie that’s already raised the prospect of a quest for transcendence, that I think more clarity might be useful.)

That inconsistency of tone struck me because I found myself wrong-footed by the movie quite a bit. There’s a considerable amount of cleverness in its set-up, but little clear comedy. There’s a strong satirical and absurdist tone, but not much sense of anything in particular being satirised — you could say modern consumerist society and the drive for success at all costs is the focus of satire, but then you could also say that the drive for individual transcendence is also being satirised at the same time. It might be meant as a tongue-in-cheek look at one person’s internal voices, but most of the characters don’t clearly represent an obvious drive. And then some elements, such as the voice on the radio, simply feel unmotivated or unclear in their meaning. (I note that while watching the movie I interpreted that voice as probably satanic or infernal, while McCabe-Lokos noted in the q-and-a that his idea was that it represents the primitive id; there are similarities between my take and his intent, but there’s enough of a difference, particularly in a movie that’s already raised the prospect of a quest for transcendence, that I think more clarity might be useful.)

The movie is engaging moment to moment. I like the absurdity of the game, and the clear arbitrariness of the set-up; it’s a very strong concept. The performances are uniformly good; the characters don’t seem to have arcs over the film, but it’s sometimes difficult to give a cartoon an arc. Maybe most importantly, while Maria’s a very quiet and even passive presence, she’s also a good choice for our point-of-view character because her quest is relatable and she quickly emerges as the most sympathetic person in the room.

The French have a useful critical term, huis-clos, which doesn’t have an exact counterpart in English. It’s the name of the Sartre play translated in English as No Exit (the one with the quote “hell is other people”), about three characters stuck in a room together who over the course of the story bring out the worst in each other. Huis-clos in French now means a story about characters stuck in a room together and their interactions in that space. How they interact, often enabling each others’ worst aspects, is typically the focus of the story. So it is here. But if there is a theatrical feel to the film, the examination of character interaction in a confined space works. The absurdity of the situation gives the competition an edge; it’s all so arbitrary, and yet so meaningful in the moment to each of the characters.

That’s the saving grace of the film. The characters are interesting enough one is carried past the lack of explanations for all the things that happen around them. But then there comes a point where one wonders about their actions — say, why they’re not demanding more and better answers, and why some of them are putting up with all the stuff they’re going through for a reward that’s relatively small. In other words, consistency of character is where the movie works and where it falls apart. Stanleyville is ambitious, and often interesting, but in the end neither its characters nor its absurdity are quite enough to carry it.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.