Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: When History Gets in the Way of a Good Story

It’s been a little while since we visited. If you don’t recall, last time, I took to task G. Willow Wilson for writing a lovely tale in The Bird King, that at the same time it has been hailed for providing strong feminist and Muslim characters, did so by perpetuating centuries old stereotypes about the Spanish Inquisition and creating antagonists that literally could never have existed. In short, to tell the tale she wanted, Wilson mangles Iberian history, and doesn’t provide so much as a footnote to acknowledge it.

I ended that column with:

Wilson is one of a number of authors doing a beautiful job of mainstreaming and normalizing Muslim characters and settings in fiction. But it is problematic doing so while promulgating false historical narratives. Please, give us a more realistic presentation, a detailed Author’s Note at the end, or just make it a secondary world that is so obviously based on our own, but the names have been changed to protect the guilty. Guy Gavriel Kay has made an entire career at just this, and is probably blurring the line between Historical Fantasy and Low Fantasy. He’s absolutely one of my favorite writers.

Now, I get to have my Marc Antony moment: Friends, Readers, Countrymen, I come to critique Guy Gavriel Kay, not to praise him….

Kay is undoubtedly one of the most celebrated fantasy writers alive. Which is ironic, since, after Tigana, one of the most compelling, character-driven high fantasy novels you will read, he really has never written another fantasy novel, other than 2007’s contemporary fantasy Ysabel – his tenth novel!

Beginning with a Song for Arbonne, set in a mythical Aquitaine, Kay has been steadily building his own mythic Europe, where the kingdoms and personalities have different names, and events transpire somewhat differently, but which feels familiar and “real” none-the-less. There are no elves, no faeries, no dragons, no magicians. The bits of magic that DO appear are more like “magical realism” and add color, but has little import on the plot. The one piece of magic in Arbonne proves not to be magic at all; alchemy has a minor role in Lions of Al Rassan, and the magical elements of the Sarantium Mosaic could easily be seen as examples of characters’ intuition, assumptions, “inner voice”, etc. In many ways, Kay’s fantasy is more that used as early as the 15th century’s Tirant lo Blanc, or by numerous romantic writers of the 18th and 19th centuries: it is not so much the overtly supernatural that makes the story fantastic as it is a romance (and the original sense) set in a some fictitious land or parallel place to our own.

In short, for most of his career, Guy Kay has been writing historical fiction with flourishes of magical realism, masquerading as fantasy. I suspect because a) fantasy pays much better and b) he can tell his tale as he wishes, without the constraints of history. A Song for Arbonne has its own Marie of France (12th c), a form of the Albigensian Crusade (13th c), and a goddess cult that is one part medieval Cult of the Virgin, a dash of grail mythos and a healthy dose of 19th c Celtic Revival. Lions of Al Rassan is the Son of the Cid (11th c Spain), with the Middle Eastern cult of Assassins (12th – 14th c), and a love triangle clearly drawing from “Ivanhoe”. The Sarantine Mosaic is about Byzantium during the time of Justinian I, and so on.

Children of Earth and Sky brings us to Kay’s Renaissance, specifically a time equivalent to the late 15th c, where Sarantium has been overrun 25 years earlier by the aggressive Ottoman… er… Osmanli Empire and its Jannisaries… er… Jani. The only real power against the Osmanli’s is the city-state of Seressa (Venice, which has been known for centuries as La Serenissima) and its client states.

Sounds great! I settled in to see how this version of the late 15th century would play out…

Locations:

- Seressa is Venice

- Dubrava is Dubrovnik

- The Senjani are the Uskoks, who had a fortress of Sanj.

- The Osmanli are the Ottoman Turks.

- The Holy Jaddite Empire is the Holy Roman Empire

The first problem. This time, Kay’s formula doesn’t work. Or rather, maybe it does, if one is ignorant of the history and locale. As I said, his world is a tweaked version of our own. This time, however, there are no tweaks worth mentioning… this is just a story of the 15th century Balkans, with the names changed (barely).

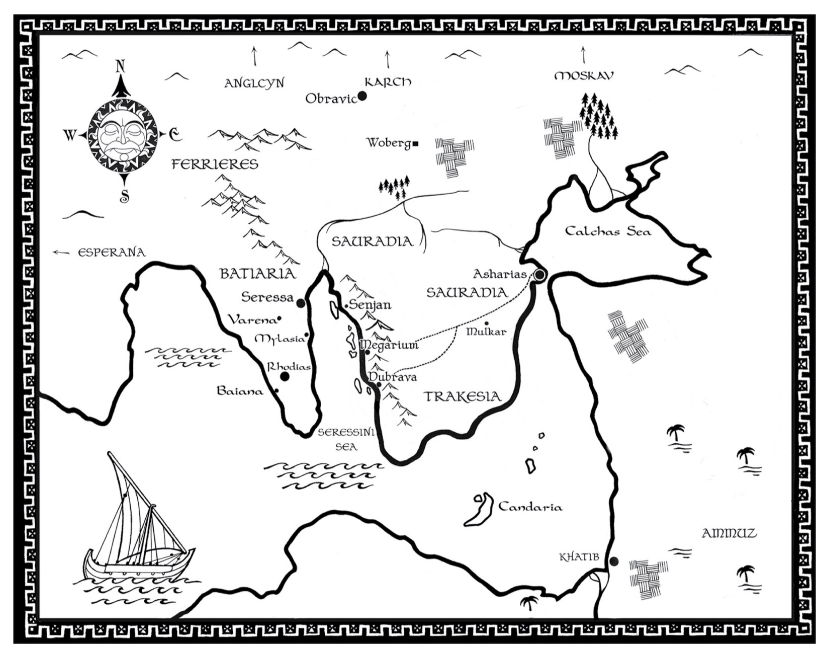

You barely have to squint to recognize that coastline, eh?

That’s typical in Kay’s writing — he isn’t trying to hide that Sarrantium is Byazantium, or Seressia Venice, but here almost all of the characters are thinly veiled real people as well — including the main POV characters (noted with an asterisk):

Characters

- Orso Faleri* = Andrea Gritti, Venetian ambassador and later Doge

- Emperor Rodolfo = Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Pero Villani* = Gentile Bellini, Venetian artist

- Duke Ricci* = Leonardo Loredan, Doge of Venice

- Empress Eudoxia = Helena Dragaš, last Empress of Byzantium

- Hrant Bunic = Nikola Jurišić of Serj

- Grand Khalif Gurçu “the Destroyer” = Mehmed II the Conqueror

- Prince Beyet = Bayezid II, Mehmed’s son and heir

- Prince Cemal = Cem, Mehmed’s younger son

- Rasca Tripon, called “Skandir”* = Skanderbeg, war lord and national hero of Albania

The Djivo family shares several first names and some similarities to the Kaboga family, part of Dubrovnik’s aristocracy for generations.

The only major characters who are not thinly veiled historical figures are Danica Gradek, her brother Nevyn, and one of the Djivo family. As always, the characters themselves are richly drawn, but the historically-derived characters hone so close to their prototypes as to be without any notable difference. Unfortunately, our most notable original character, Danica, is a Mary Sue. She never misses with her bow, she never fails to be in the right place at the right time, she beds the powerful men she encounters (while remaining emotionally distant), she finds her lost brother, etc., etc. She does whatever she wants, everyone acquiesces to her demands with surprising ease, and she always proves to be right. It just reduces the character to someone… well… uninteresting.

In short, this is really an historical fiction novel with a mild dose of historical realism, not a fantasy — or rather, not what that term has come to mean. And the challenge of historical fiction, and one reason I think Kay likes having his secondary world, is that history doesn’t provide neat and tidy plots, character arcs, etc. Not only do the good guys not always win, they don’t always lose in terribly dramatic or interesting ways. We rarely have clear heroes or villains, and the latter often escape justice, or are taken down unexpectedly, even insipidly.

Usually, the brilliance of Kay’s formula is that he can escape those problems since his stories are in a secondary world, whose history is at his command. Only not this time. If the first problem with this book is that you could just make this the 15th c Balkans, give everyone their original names and it would be a fairly accurate historical fiction novel about Gentile Bellini’s journey to paint the portrait of Mehmed the Conqueror and his brief encounter with Skandbeg, the second problem is — nothing really happens.

Yes, there are a few battles, a ship raid, a daring escape… but for 575 pages, everything moves smoothly. Bellini… er… Villani gets to the court (very late in the book), gets caught in a fratricidal plot… and extracts himself with a short conversation, the repercussions of which happen off-stage. Although a few of the battles seem desperate, none of the major characters really find themselves in true trouble — every time they might get caught, arrested, killed, poisoned it turns our A-OK, and the villains somewhat incompetent, or at least easily thwarted. As for the ghosts, they are a narrative device more than a plot point (with one notable, if small exception). Remove them and nothing changes in the overarching tale.

This may be the most disappointing of Kay’s novels I have read, simply because, after getting 80%, maybe more, of the way through the book, for what seems to be the set-up for another duology, everything begins to swiftly resolve, often through exposition, rather than action. The last two chapters of the novel end with sweeping narratives of the character’s return journey, and in many cases, what happens over the rest of their lives. It’s the kind of sweeping epilogue that appears in books like The Lord of the Rings and Lonesome Dove, grand epics about characters who have endured a brutal journey of hardship and discovery together. Here, such an extended resolution is beautifully written but wasted on this story — many of the characters have only the most tangential of relationships, the events they endured transpired over a few weeks, and the spy mission on behalf of Seressa that no less than two characters were charged with, never actually happens.

There is action, but no tension, and the world is little different than when we arrived — between consequential moments in history. If Wilson’s The Bird King commits the sin of mangling history to create the story she wants to tell, Kay here is guilty of the inverse — being so slavishly faithful to the history of the real-world characters and events he wants for which he wants to create a parallel chronicle, he is stuck telling a tale that really has little tension or resolution, because their real-world individuals had their own stories resolve at times unrelated to this journey.

In the tension between historical fidelity and good story-telling, the whole point of a secondary world should be that you are freed of the constraints of the former in service of the latter. That rule has served Kay well in earlier works, but he traps himself here. It is a rare misstep by a brilliant writer, but it provides a useful reminder that while history may not be concerned with providing a clear and entertaining narrative, fiction should be.

Excellent piece! Kay is a giant, but I think you put your finger on why I didn’t go nuts over his work–it wasn’t quite fantastical enough for me. He’s a great writer whose characters are convincing and his style is superb…but he eschews the fantastical in favor of the historical. Nothing wrong with that–he’s fulfilling his vision. This worked for George R.R. Martin in his first GAME OF THRONES book–but as that series progressed it got more and more inhabited by magic (little dragons growing slowly into big ones is the perfect metaphor for his universe getting more and more “magical” as each book progressed). Some people prefer their fantasy with minimal fantastic elements, but I’ve always been the opposite kind of reader. Turn that amp to 11. Fantasy is a wide realm and there is plenty of room for all kinds of imaginations. Smashing post!

May I suggest Glen Cook’s “Instrumentalities of the Night” series for a rather more fantastic take on thinly veiled historical novels?

Hi John,

Glad you liked it! Now, Kay can write high fantasy when he wants to: I would put his Fionavarr Tapestry against any Tolkienesque epic fantasy and say it superior to 99% of them; his Tigana has its magical premise set to 11, as you say. But yes, since then that hasn’t been his thing, and plot has never been his real centerpiece. Overall, if you like what he does, no one does it better, but this time, and for me, I find his books like a more literary version of a lot of alternate histories — what if the Song of the Cid had been crossed with Ivanhoe, etc. This time, though, he is a victim of violating his own rules.

Really glad you enjoyed the post!

Ken, I’ve read a lot of Glen Cook, though oddly enough never the Instrumentalities series.