Future History, First Draft: Robert A. Heinlein’s For Us, the Living

For Us, the Living by Robert A. Heinlein; First Edition: Scribner 2004.

Jacket illustration by Mark Stutzman (click to enlarge)

For Us, the Living: A Comedy of Customs

by Robert A. Heinlein

Introduction by Spider Robinson; Afterword by Robert James, Ph.D.

Scribner (263 pages, $25.00 in hardcover, 2004)

Almost on a lark, I picked up the first novel by Robert A. Heinlein a few days ago, and read it through. It’s a fascinating book on several levels.

First, it’s Heinlein’s first novel in that it’s the first one he wrote, way back in 1938 and 1939, when he hadn’t yet broken into print. But it didn’t sell, was never published at the time, and went unknown for decades. In fact the manuscript was thought lost; Heinlein and his wife had destroyed copies in their possession in the approach to Heinlein’s death. Yet another copy of the ms. was found years later, after Heinlein’s death in 1988, and, as Robert James explains in an afterword here, was published in 2004, with an introduction by Spider Robinson. (Spider Robinson would later publish Variable Star, based on a Heinlein outline, in 2006; I have not read that, though I believe I’ve read every other Heinlein book at least once, albeit some not in decades.) I read For Us, the Living when it first came out, in late December 2003, but didn’t remember the details of its future society, and wanted to refresh myself on them, until rereading it this week.

Second, Heinlein repurposed many of the novel’s ideas in later stories and novels, some written only a year or two later (he quickly learned how to write saleable stories).

And third, it’s remarkable how so many of these ideas anticipated real-world discoveries and ideas of recent decades. He was ahead of his time in many ways.

This novel is in the tradition of didactic utopias like Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (published in 1888) and H.G. Wells’ The Sleeper Awakes (1899), both of which involve characters from the authors’ times who become comatose in some way and wake centuries later. There were many similar novels, says Wikipedia; the motives of these weren’t to write dramatic stories in the extrapolative mode of later science fiction, but to use fictional frames to present authorial lectures about how things ought to be in the future. Many of these were socialist in nature, and they dealt with matters of politics, society, morals, and much else.

So Heinlein’s first novel isn’t much of a novel, as Spider Robinson acknowledges in his introduction. The plot is threadbare, merely a framework for much discussion of history, religion, economics, and human nature.

Outline:

- In 1939, pilot Perry Nelson, driving down the California coast towards San Diego, swerves to avoid an oncoming passing car in his lane, goes off a cliff, and dies. With an image about a girl on the beach below.

- He is found, alive, by a young woman named Diana, recognizing her as the woman on the beach (!), in the year 2086. (The coincidence of the two women, or the method of time travel to the future, is never explained.) Diana lives in the Sierra mountains with a spectacular view, and casually walks around her home naked. (Perry is obliged to do the same.) They exchange stories, and Perry gathers many things have changed in 150 years, and they quickly fall in love.

- Perry reads available books about history, to understand what’s happened since his time, while Diana has a Master from UC Berkeley visit to fill in details of that history and discuss issues with Perry, at great length.

- Diana, using her private copter, takes Perry to see San Francisco, where the streets are moving strips, and then to Monterey, where they swim. After only a couple days, they become, in effect, married.

- Bernard, a colleague/former boyfriend of Diana’s (they are both professional dancers doing a joint project) visits, and Perry jealously slugs him. Perry is taken to a city hall and then remanded to a hospital, where he undergoes psychological counseling to help him overcome the inappropriate attitudes of his past. He is encouraged to think about meanings of words, and the nature of human nature, and how it reacts to the current environment.

- He’s visited by another Master, this one to explain the economics of the era, and the mistakes made by earlier eras, at very great length.

- Free to leave his counseling, Perry and one of the hospital attendants, Olga, travel to the Grand Canyon, then to experimental grounds where a moon rocket is being developed. Perry visits Washington DC to see how the government now works.

- Perry takes to studying rocketry. He reconciles with both Diana and Olga and realizes he has overcome the attitudes of the past (i.e. they’re in a three-way relationship).

- Some time later, having developed a new powerful rocket fuel, Perry himself climbs into a rocket for the first trip to the moon.

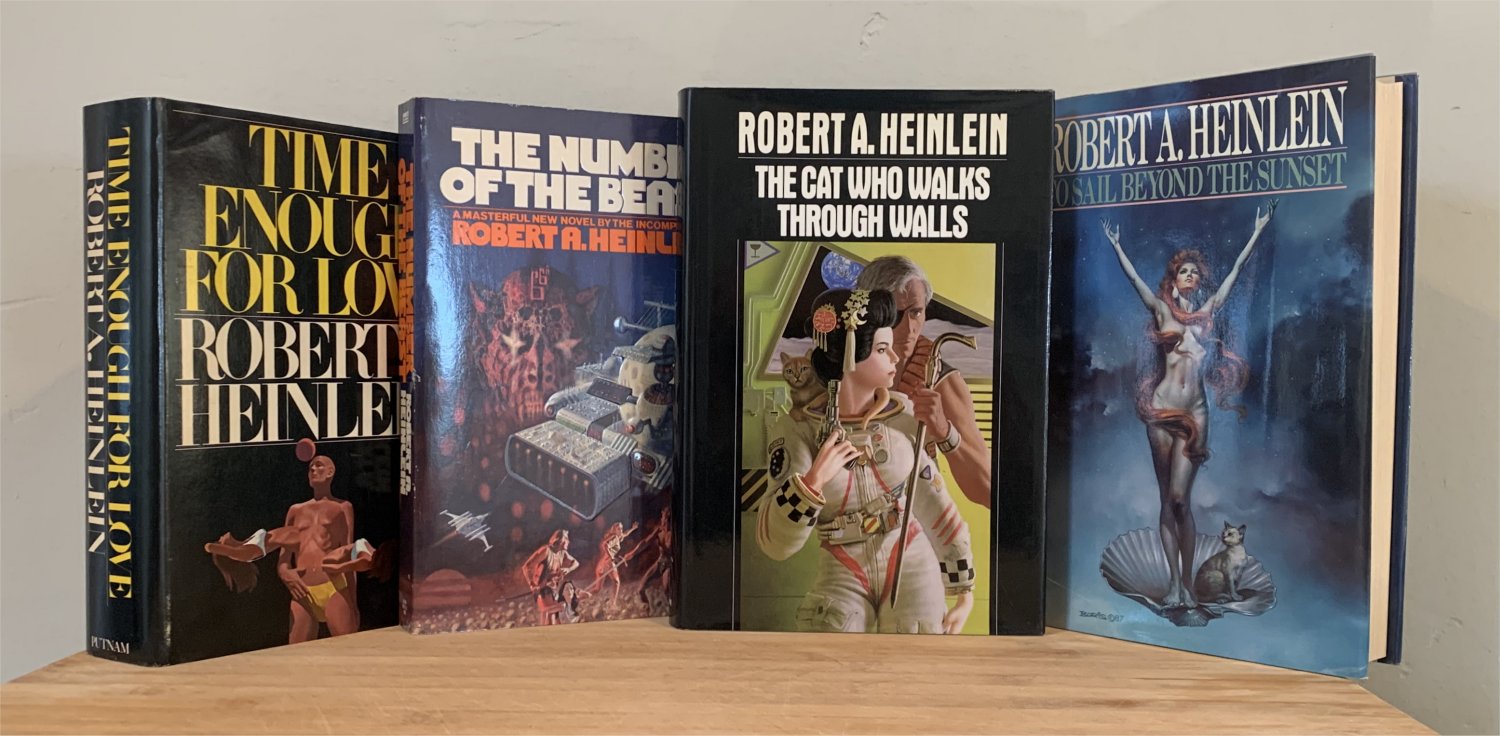

Some other Heinlein 1st editions:

Time Enough for Love, Putnam, 1973, jacket illustration by Vincent di Fate;

The Number of the Beast, Fawcett Columbine, 1980, cover by Richard M. Powers;

The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, Putnam, 1985, jacket art by Michael Whelan;

To Sail Beyond the Sunset, Ace/Putnam, 1987, jacket painting by Boris Vallejo

Key themes and ideas, with my comments [[ in double brackets ]]

- The history after 1939 includes a second world war, a 40-year European war (which the US stays out of), and an evangelical movement in the US called the New Crusade, led by one Nehemiah Scudder, whose eventual defeat results in a new Constitution. This Constitution limits laws to those prohibiting only actions that harm others, limits rights of corporations, and enshrines a right of privacy for all personal affairs. As a consequence, it also removes all laws derived merely from religious morality (that don’t involve harm to others).

- The big economic idea is that everyone, even children, get “heritage checks,” monthly grants from the government for life; as a result, there is no unemployment, and everyone enjoys a high standard of living. The key is money: what is it? No, not gold, that was a big mistake of the early 20th century. Money is a medium of exchange that works because everyone believes it works.

- [[ This is exactly Harari’s thesis in Sapiens. And the idea of a universal basic income, floated around for decades, has gained prominence recently from Rutger Bregman and Andrew Yang. According to Robert James’ afterword, ideas about “Social Credit Theory” had been in the air for some time when Heinlein wrote. ]]

- Over-production, not the profit system, was the problem in 1939. Knowledge accumulates. The answer is to create new money as needed to balance the production cycle. Further, value is not, as Marx thought, the number of work-hours to produce a given article. Value is about customer desire, how much the customer wants a particular article.

- [[ And this correlates with modern psychological thought about happiness, which doesn’t have an objective measure, but rather depends on your perception of your status relative to those around you; thus “keeping up with the Jones.” ]]

- But doesn’t this system subsidize laziness? No, the way to look at it is to consider that modern humans are living off the accumulated knowledge and discoveries of the past; there isn’t enough drudgery to go around.

- [[ Again, anticipates Harari and others in worrying whether machines will render many jobs obsolete. Perhaps so; the answer is that universal basic income. In 2086, Heinlein suggests, most people aren’t indolent and work anyway, or find some private project to pursue. ]]

- [[ My own thought, which I can’t point to a source just at the moment, is that the cost of subsidizing a minority of lazy people is far less than the cost of the infrastructure to decide who’s eligible for government “assistance” and prevent the lazy from getting it. Dismantle the infrastructure — shrink the government! — and just give everyone the money, as Alaska does in some limited sense. The issue then becomes the “moral” one of rewarding people who don’t work; in the Puritan ethic, still deeply embedded in some of American culture, work, now matter how menial, is supposedly virtuous. ]]

- On the matter of human nature, as Perry is “treated,” he is asked to define terms, first common ones like apple and cat, then abstract ones like patriotism, duty, honor, society, and truly think about what these mean. This future society has developed a Code of Customs based on conclusions reached through understanding of the real world (the only alternative being revelation). These conclusions have always been available, but were resisted. Still, Perry can’t help feeling jealous; that incident with Bernard. His mentor explains that while “human nature” may exist, the environment changes and how human nature responds thus changes. So flying in a copter despite fear of heights; thus belly hunger doesn’t trigger ravenous reactions to the sight of food. Males and females have different reasons for sexual jealousy — males, to defeat other males for the right to mate; females, to ensure her partner remains loyal to her and her children.

- [[ And this remarkably anticipates the conclusions of sociobiologists of recent decades, about the differing reproductive strategies of males and females, and the recognition that male and female brains are not identical, nor that they are “blank slates.” Examples in E.O. Wilson’s On Human Nature and Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate. ]]

- And so with personal affairs a matter of privacy (i.e. no one possesses anyone), and everyone including children take care off by the state, the old jealous reactions about mates can be unlearned or disregarded.

- [[ As a personal aside, this is how, in my experience, the gay community works. Two men can date for a while, call it off, and still be good friends, still be part of the same social groups, without the poisonous jealousy or resentment that characterizes the worst breakups between straights. Heinlein is imagining that, with all personal relationships shielded from opinion of others by the policy of privacy, and that children are supported by the state as necessary, jealousy and possessiveness among straights can as well be circumvented. Though I might mention there’s never the slightest hint in this book that there might be relationships between two men or two women; Heinlein’s world is entirely heterosexual. ]]

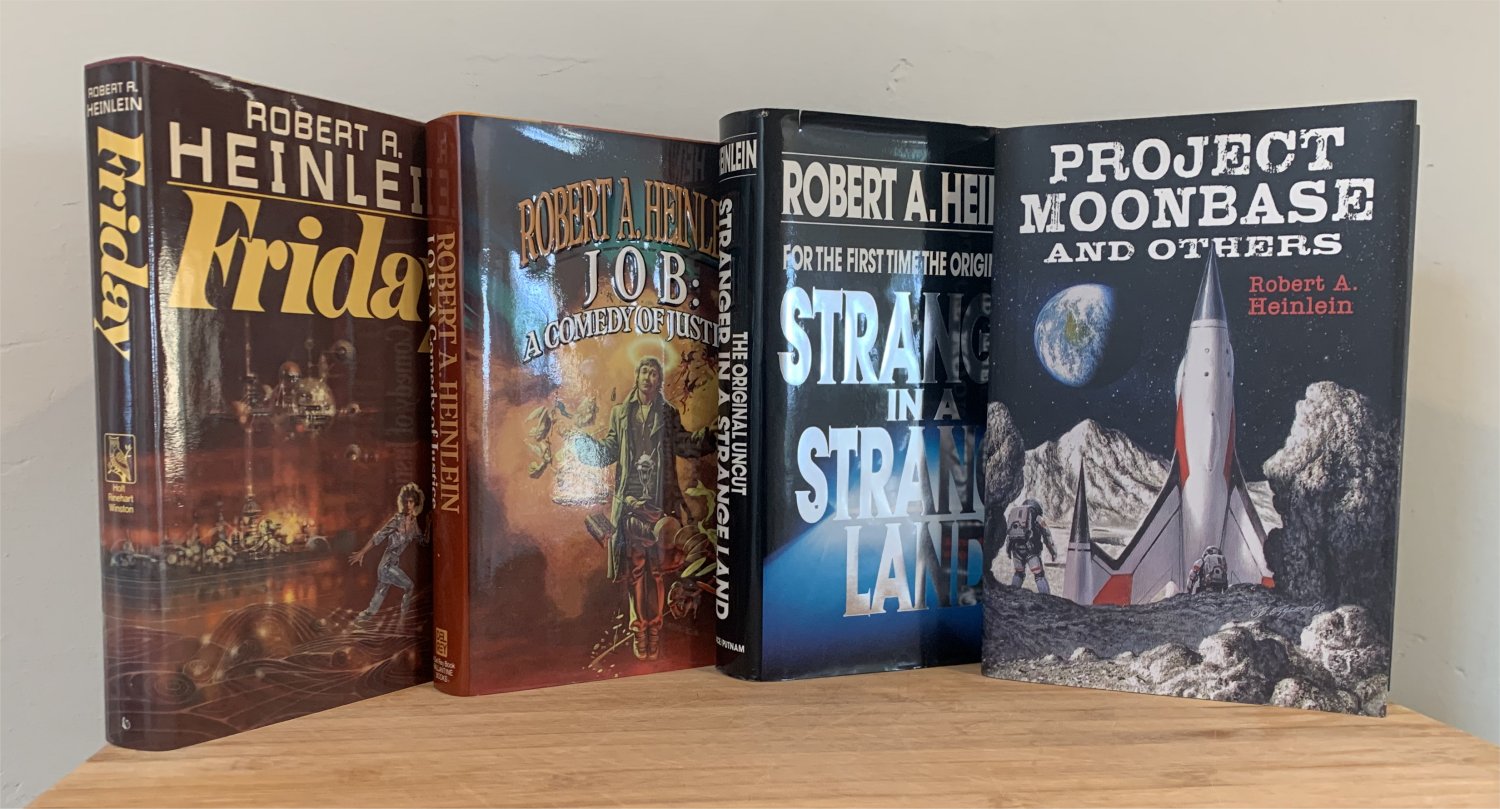

And a few more Heinlein 1st editions:

Friday, Holt Rinehart Winston, 1982, jacket illustration by Richard M. Powers;

Job: A Comedy of Justice, Ballantine/Del Rey, 1984, cover painting by Michael Whelan;

Stranger in a Strange Land (original uncut edition), Ace/Putnam, 1991;

Project Moonbase and Others, Subterranean, 2008, dustjacket illustration by Bob Eggleton

Some of these ideas about economics, about Social Credit Theory, I gather, show up in Heinlein’s 1942 novel Beyond This Horizon, which I haven’t read in decades, but will revisit soon.

Meanwhile, there are several other specific ideas that Heinlein entertained in this novel, that later became themes of later stories:

- The moving streets were the subject of “The Roads Must Roll,” published in June 1940 (in Astounding of course).

- Perry is given the choice of psychological treatment or deportation to “Coventry,” a reservation for non-compliant individuals that one enters and never leaves (in effect, an anarchy). An entire story about it, with that title, was published in July 1940.

- And the narrative about the religious takeover of the US is told in “If This Goes On—” published in February and March 1940. Though it’s not the story of Nehemiah Scudder himself (Heinlein never did write that story, he admitted, disliking the character too thoroughly.) I blogged about this story back in 2015.

- More incidentally, everyone smokes constantly in this novel. I don’t recall if that was true in Heinlein’s later stories, though I recall smoking, mostly of cigars, was common in Asimov stories of the 1940s and ’50s.

- And Heinlein was always attracted, throughout his career, to the idea of casual nudity and to open and multiple relationships. I’m afraid I don’t buy the casual nudity for a moment, except possibly among partners in a sexual relationship in the privacy of their home. Otherwise, it would be too distracting! And likely disgusting. How many of your colleagues, or neighbors, would you want to see naked?

Finally I’ll quote a passage, spoken by the historian from Berkeley, about religion and its role in society. Some of these lines did show up in “If This Goes On—,” as quoted in my post linked above. Pages 83-84:

“All forms of organized religion are alike in certain social respects. Each claims to be the sole custodian of the essential truth. Each claims to speak with final authority on all ethical questions. And every church has requested, demanded, or ordered the state to enforce its particular system of taboos. No church ever withdraws its claims to control absolutely by divine right the moral life of the citizens. If the church is weak, it attempts by devious means to turn its creed and discipline into law. If it is strong, it uses the rack and the thumbscrew. To a surprising degree, churches in the United States were able, under a governmental form which formally acknowledged no religion, to have placed on the statutes the individual church’s code of moral taboos, and to wrest from the state privileges and special concessions amount to subsidy. Especially was this true of the evangelical churches in the middle west and south, but it was equally true of the Roman Church on its strongholds. It would have been equally true of any church; Holy Roller, Mohammedan, Judaism, or headhunters. It is a characteristic of all organized religion, not of a particular sect.”

This is the sort of matter-of-fact attitude about religion that pervades most science fiction about the future, though it’s rarely stated as explicitly as this. It’s not meant to be controversial, or contentious, it’s just stating what’s obvious.

An earlier version of this article first appeared at View from Crestmont Drive.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was Isaac Asimov’s Pebble in the Sky. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive.

[…] Fiction (Black Gate): First, it’s Heinlein’s first novel in that it’s the first one he wrote, way back in 1938 […]

[…] Fiction (Black Gate): First, it’s Heinlein’s first novel in that it’s the first one he wrote, way back in 1938 […]