IMHO: A Personal Look at Dystopian Fiction — Part One

|

|

|

For the sake of this 2-part article, and not wanting to rely on memory alone, I’ve used a brief synopsis of each novel mentioned here, courtesy of Wikipedia.

I haven’t read a dystopian novel in decades. Why? First, because I’ve read enough of them and after a while I got burned out. Second, because I started to see the direction in which our governments and our world were and are heading. Reality intruded upon fiction, and such novels began to depress me, even if they ended on a happy, upbeat and optimistic note. I now read for escapism, to be entertained, or educated if I’m reading history or biographies.

During the Depression of the 1930s, and even through WWII, escapist entertainment was extremely popular, especially in films, because people wanted to forget, even for a few hours, what was happening in the real world. Today, in the Information Age, we are bombarded by both real and fake news, and by the landslide of dark, world events. And yet, dystopian fiction, in both literature and the cinema, are more popular now than ever. Is this the new escapist entertainment for the 21st century? Perhaps. Now, I don’t know what every writer and film maker had or has in mind, but I do know that in the past, authors always had a clear agenda: they were writing cautionary tales.

What I intend to do with the first part of this 2-part article is to introduce readers to early and perhaps all but forgotten dystopian novels that I’ve read. These are books I think should not be forgotten, books that are must-read novels. Part 2 will deal with more recent fiction, as well as an “incomplete/partial” list of films. So let’s begin, shall we?

[Click the images for dystopian-sized versions.]

Probably the most famous of all dystopian novels is 1984. Written in 1949 by George Orwell, this novel has twice been made into films, to my knowledge. The novel is set in Airstrip One, formerly Great Britain, and a province of the super state called Oceania, whose residents are victims of perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance and public manipulation. Oceania’s political ideology, euphemistically named English Socialism (shortened to “Ingsoc” in Newspeak, the language invented by the government) is enforced by the privileged, elite Inner Party. Via the “Thought Police,” the Inner Party persecutes individualism and independent thinking, which are regarded as “thoughtcrimes.” (While Orwell’s Animal Farm is a satirical tale about Joseph Stalin and Communist Russia, it can also be considered a dystopian novel.)

Another famous dystopian novel is Brave New World, written in 1931 by English author Aldous Huxley, and published in 1932. Set in London in the year AD 2540, the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology, sleep-learning, psychological manipulation, and classical conditioning that are combined to make a profound change in society. The novel opens in the World State city of London, where citizens are engineered through artificial wombs and childhood indoctrination programs into predetermined classes (or castes) based on intelligence and labor. It has been adapted for the theater, radio and two television movies.

One of the earliest dystopian novels I can think of and which I first read sometime in the 1970s is HG Wells’ 1910 classic, When the Sleeper Wakes, also known as The Sleeper Awakes. This science fiction novel is about a man who sleeps for two hundred and three years, finally waking up in a completely transformed London where he has become the richest man in the world. Although his dreams are fully realized, the future is revealed to him in all its horrors and deformities.

While Wells’ 1933 The Shape of Things to Come speculates on future events from 1933 until the year 2106. The plot is straight-forward, and quite realistic, perhaps even prophetic. A long economic slump causes a major war that leaves Europe devastated and threatened by plague. The nations with the strongest air-forces set up a benevolent dictatorship that paves the way for world peace by abolishing national divisions, enforcing the English language, promoting scientific learning, and outlawing religion. The enlightened world-citizens are able to depose the dictators peacefully, and go on to breed a new race of super-talents, able to maintain a permanent utopia. It has inspired at least two motion pictures. It begins on a dark and dour note, but most definitely ends with the hope and promise of a much brighter future.

Sadly, an all but forgotten novel, The Iron Heel, is a dystopian thriller written by American writer Jack London and first published in 1908. This novel frightened me when I read it, because I could see the parallels in what was happening in the world today, and in what direction I fear the world is heading. Generally considered to be “the earliest of the modern dystopian” fiction, it chronicles the rise of an oligarchic tyranny in the United States. It’s a very dark, grim story, and arguably the novel in which Jack London’s socialist views are most explicitly on display. A forerunner of soft science fiction novels and stories of the 1960s and 1970s, the book stresses future changes in society and politics while paying much less attention to technological changes.

|

|

|

It Can’t Happen Here is a semi-satirical 1935 political novel by American author Sinclair Lewis. Published during the rise of fascism in Europe, the novel describes the rise of Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, a politician who defeats Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and is elected President of the United States after fomenting fear and promising drastic economic and social reforms while promoting a return to patriotism and “traditional” values. After his election, Windrip takes complete control of the government and imposes a plutocratic/totalitarian rule with the help of a ruthless paramilitary force, in the manner of Adolf Hitler and the SS. The novel’s plot centers on journalist Doremus Jessup’s opposition to the new regime and his subsequent struggle against it as part of a liberal rebellion. While it may seem outdated to some readers, it is still a powerful novel about a very frightening and possible future. Perhaps a future that is already here.

The books I have already mentioned are, to my knowledge, some of the earliest-known dystopian novels, books that I’ve read in the last 4 decades of the 20th century. Besides being classified as science fiction or dystopian fiction, to me they’re really horror novels, more or less. (As for horror novels… I don’t think of them as such. I think of them as dark fantasies, with supernatural or paranormal elements — and I do accept the existence or the possibility of both. The only “horror” novel that actually creeped me out, and gave me a nightmare or two was The Exorcist.) But dystopian novels such as George Orwell’s 1984, Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here, and Jack London’s The Iron Heel really got to me, and those are the real horror stories.

In this next part I’m going to discuss a few dystopian novels published in the latter part of the 20th century, novels I consider to be of some importance, novels I feel should be read by those who read and write dystopian fiction. I just hate to see really great novels go unread and forgotten by today’s reading audience, and in many cases, younger readers may not even be aware of these novels. So hopefully I will be turning some people on to a few really great novels.

|

|

|

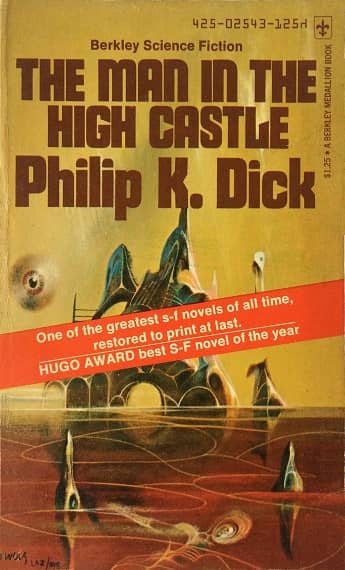

First: a big shout-out to the late, brilliant Philip K. Dick. Many, many of his novels take place in dystopian futures: this was his niche. And he seems to be as popular with young readers today as he was when I first discovered him in the 1960s. He was one of a kind, a truly unique and gifted writer. A number of his novels and stories have been turned into films, such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (filmed as Blade Runner), short story “The Minority Report, “(filmed as Minority Report), A Scanner Darkly, The Man in the High Castle, and “Second Variety” (filmed as Screamers.) He is one of the greats of classic science fiction, with a voice like no one else. His is most definitely a must read.

So onward we go…

|

|

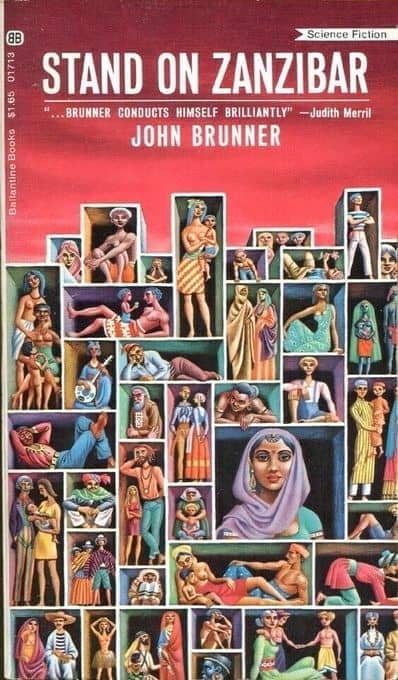

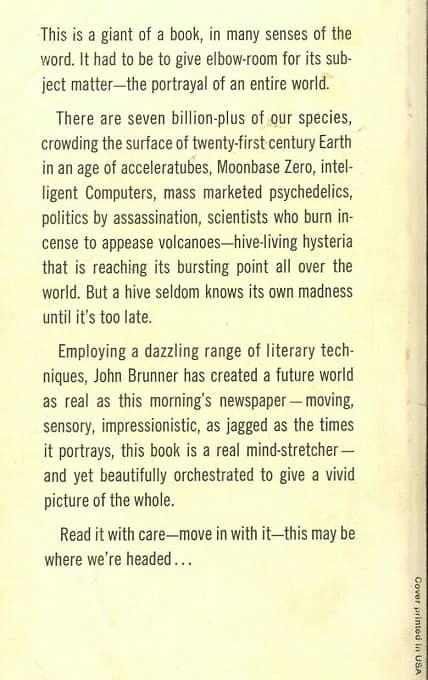

Although I had read 1984 and Brave New World in high school, the first dystopian novel I read on my own — long before the “label” was attached to such fiction, was John Brunner’s Stand On Zanzibar. This novel was part of 1960’s New Wave of science fiction. Published in 1968, the book won a Hugo Award for Best Novel at the 27th World Science Fiction Convention in 1969, as well as the 1969 BSFA Award and the 1973 Prix Tour-Apollo Award. Stand on Zanzibar was innovative within the science fiction genre for mixing narrative with entire chapters dedicated to providing background information and world-building, to create a sprawling narrative that presents a complex and multi-faceted view of the story’s future world. Such information-rich chapters were often constructed from many short paragraphs, sentences, or fragments thereof — pulled from sources such as slogans, snatches of conversation, advertising text, songs, extracts from newspapers and books, and other cultural detritus. The novel’s story is overpopulation and its projected consequences. Brunner remarked that the 3.5 billion people living in 1968 could stand together, upright and shoulder to shoulder, on the Isle of Man, 221 square miles, while the 7 billion people whom he (correctly) projected would be alive in 2010 would need to stand on Zanzibar, 600 square miles. The story is set in 2010, mostly in the United States. A number of plots and many vignettes are played out in this future world, based on Brunner’s extrapolation of social, economic, and technological trends. The key main trends are based on the enormous population and its impact: social stresses, eugenic legislation, widening social divisions, future shock, and extremism.

|

|

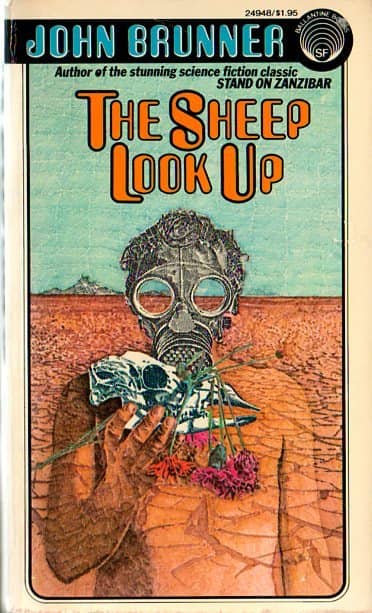

John Brunner followed up with The Sheep Look Up, first published in 1972. The novel’s setting is decidedly dystopian; the book deals with the deterioration of the environment in the United States. It was nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1972. With the rise of a corporation-sponsored government, pollution in big cities has reached extreme levels and most (if not all) people’s health has been affected in some way. By the end of the book, rioting and civil unrest sweep the United States, due to a combination of poor health, poor sanitation, lack of food, lack of services, ineffectiveness of services (medical, policing), disillusionment with government/companies, oppressive government, high incidence of birth defects (pollution-induced), and other factors. All services, such as military, government, private, and infrastructure, eventually break down. This is truly a realistic horror novel.

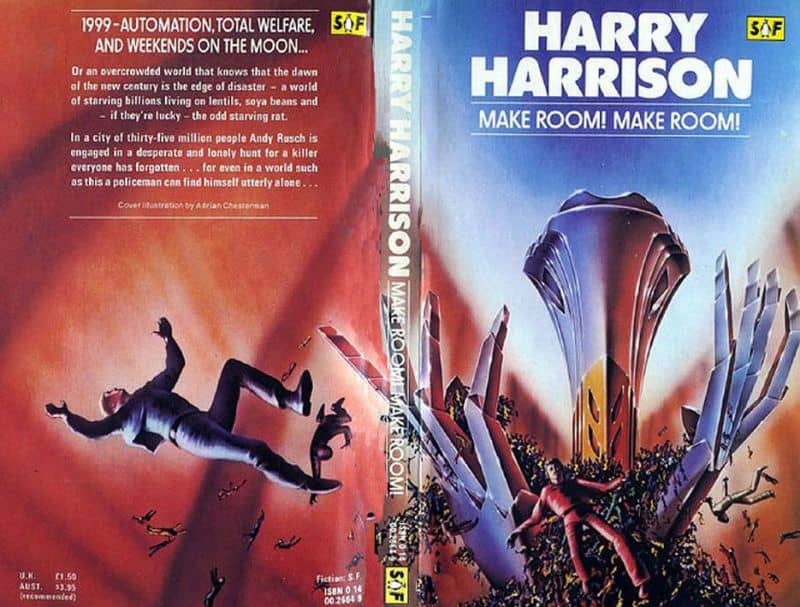

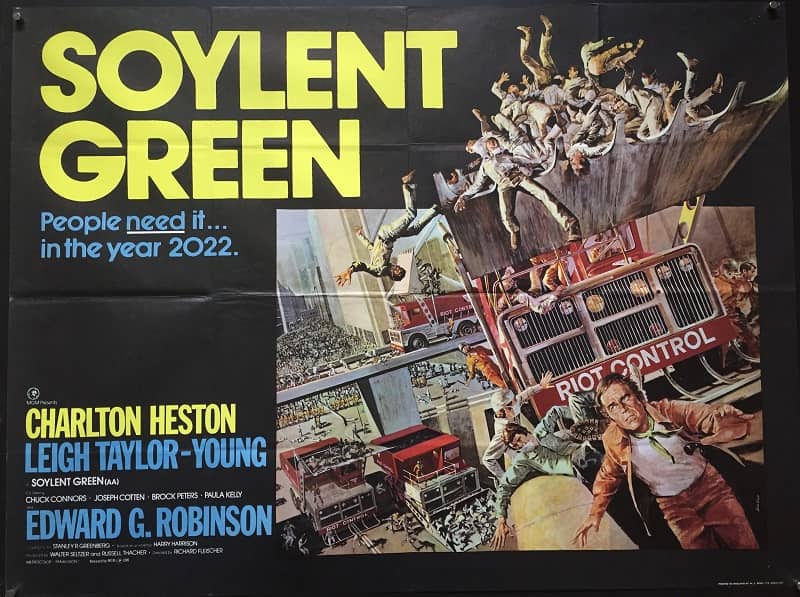

Probably one of the more famous, latter-day novels of a dystopian future, thanks to the popularity of the film, Soylent Green, is the novel which inspired the movie: Harry Harrison’s novel Make Room! Make Room! Published in 1966, the novel is set in the then far-future of August, 1999. Harrison explores trends in the proportion of world resources used by the United States and other countries compared to population growth, depicting a world where the global population is seven billion, subject to overcrowding, resource shortages and a crumbling infrastructure. The plot jumps from character to character, recounting the lives of people in various walks of life in New York City (population around 35 million).

The novel differs greatly from the film, which has become its “own thing.” In the movie, character names have been changed, the murder investigation is never solved, and “soylent green” is just a simple cracker made of soy beans and lentils, and had almost nothing to do with the plot of the story, not in the way it figured so memorably in the film version. I applaud the screenwriters for taking that “simple cracker” and turning it into the crux of the plot, and for adding the element of cannibalism to the story. Spoiler Alert! Making soylent green out of dead people sure solves the problems of both food shortage and dead body disposal.

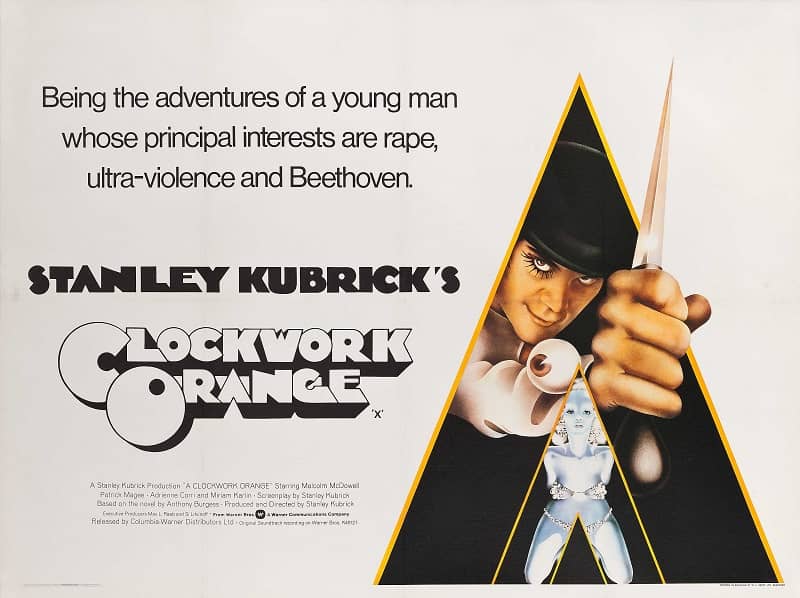

Another famous dystopian novel, made even more famous by Stanley Kubrick’s film version, is Anthony Burgess’ 1962, A Clockwork Orange. Set in a near future English society featuring a subculture of extreme youth violence, the teenage protagonist, Alex, narrates his violent exploits and his experiences with the state authority’s intent on reforming him. The book is partially written in a Russian-influenced argot called “Nadsat.” According to an essay by Burgess, the title of the book “would be appropriate for a story about the application of Pavlovian or mechanical laws to an organism which, like a fruit, was capable of color and sweetness.” Or something organic that is mechanically controlled, as one friend described it.

I found both the book and the film to be a dark and disturbing look at a possible future controlled “by the state,” but where gangs roam free and control the streets, practicing their “bit of the ol’ ultra-violence” on innocent victims, just for the fun of it. While not as much of a futuristic horror story as other dystopian novels, it is definitely a most influential novel, even prophetic novel, but not one I’ll ever read again. For me, it was not a pleasant read.

|

|

Lastly, I come to another famous dystopian novel, this won written by one of the masters of Science Fiction, and of short stories in particular: Ray Bradbury. I’m talking about Fahrenheit 451, of course, which has been turned into two films, as of this date. This is a dystopian novel, published in 1953, that presents a future American society where books are outlawed and “firemen” burn any that are found. Fahrenheit 451 is the temperature at which book paper catches fire and burns. The novel has been the subject of interpretations focusing on the historical role of book burning in suppressing dissenting ideas, such as the books burned by the Nazis, as well as here in the United States; so many more books have been removed from school libraries, too. In a 1956 radio interview, Ray Bradbury stated that he wrote Fahrenheit 451 because of his concerns at the time (during the McCarthy era) about the threat of book burning in the United States. In later years, he described the book as “a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.” How true! I’m very proud that my first published short story, in 1984, and in an amateur “fanzine” called Orion’s Child, appeared with a previously-published story Ray Bradbury that he donated to help us sell magazines. Better than that, my name is on the magazine’s cover, right near his!

That’s all for now, folks. In Part 2, I wind up this article by discussing some other writers of dystopian fiction, listing book titles, and even the recent spate of popular movies.

Joe’s last article for Black Gate was an excerpt from his Three Against the Stars novel The MechMen of Canis-9.

Thank you, John O’Neil once again. This time you really outdid your usual excellent work with this fantastic presentation of my article. I hope people enjoy it.

Great overview, Joe. The fact that the previous dystopian views have become realized… we have reason to be cautious about our future! I wonder about current (~2019) visions of our future (>2050).

Thank you, SELindberg. Glad you enjoyed this one. I agree with you about our current world and what the next 30 years or less will bring about. Hope you enjoy Part 2. I’ll have another one coming soon – about my take on making dialog very integral to plot and characters.

Merchant’s War? Canticle for Leibovitz?

fhb3,

Nice picks — but Pohl’s MERCHANTS WAR is a little too recent (1984). Part II will deal with more recent books.

Or did you mean Cherryh’s Merchanter novels?

I never could get through Canticle – too slow-moving for me, and totally forgot about it until now. Merchant’s War or Merchanters . . . I didn’t think of those, either. The list is by far incomplete. My memory isn’t what I remember it being, and there are so many books I never read. And like I said, I stopped reading dystopian fiction years ago, because the future is now.

I think Wells’ Shape of Things to Come is more future history than dystopia. As you say, it ends on an optimistic note. A similar book is Stapledon’s Last and First Men, which you could argue has a series of dystopias within its epic sweep. We by Yevgeny Zamyatin was written in the 1920s and is said to have influenced Orwell. It depicts a rigidly organized society where people have little privacy and no room for individual thought. The narrator meets a young woman who has her own ideas and the two become lovers. You can see the similarities between this comment on Soviet society and Orwell’s novel. Another novel you might consider is Mordecai Rochwald’s Level Seven in which the narrator tells of his being chosen to live in a sophisticated nuclear bunker and of his experiences there. Lastly, although it is decades since I read it, I think of Arthur C Clarke’s The City and the Stars as having a dystopian element. The City of the title is too perfect and too boring and the plot revolves around how the chief character breaks out of the stifling regime.

NeilH – I pretty much agree with you on Wells’ novel, although my take on it, which is the aftermath of devastating wars, as showing us a dystopian future. As I said, there are many, many books I didn’t bother to mention – either because I didn’t read them or they didn’t work for me. Thank you for adding more titles to the list, my friend.

A fine post.

I have fond memories of Walter Tevis’s Mockingbird. I recall it ending on a slightly more hopeful note than most dystopias.

Thank you, Sarah Avery. I don’t know how I could have neglected “Mockingbird.” Must be old age creeping in.